Audience

This report is part of a series of cyber threat assessments focused on Canada’s critical infrastructure. It is intended for leaders in the marine transportation sector, cyber security professionals with maritime infrastructure to protect, and the general reader with an interest in the cyber security of critical infrastructure. For additional information on technical mitigation of these threats, consult the Canadian Centre for Cyber Security’s (Cyber Centre) guidance or contact the Cyber Centre.

Contact

For follow-up questions or issues, contact the Cyber Centre by email at contact@cyber.gc.ca.

Assessment base and methodology

The key judgements in this assessment rely on reporting from multiple sources, both classified and unclassified. The judgements are based on the knowledge and expertise in cyber security of the Cyber Centre. Defending the Government of Canada’s information systems provides the Cyber Centre with a unique perspective to observe trends in the cyber threat environment, which also informs our assessments. The Communications Security Establishment Canada’s foreign intelligence mandate provides us with valuable insight into adversary behaviour in cyberspace. While we must always protect classified sources and methods, we provide the reader with as much justification as possible for our judgements.

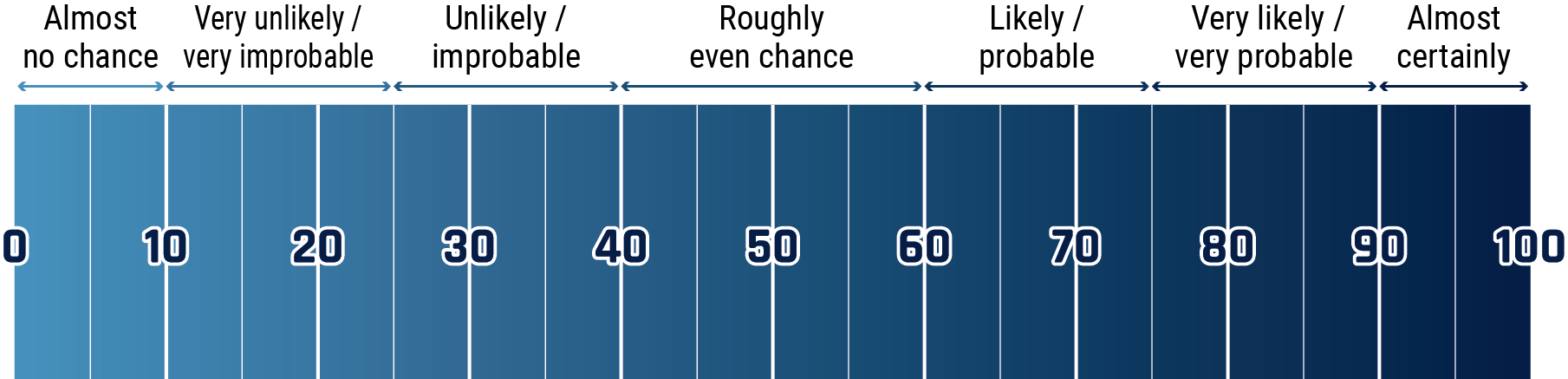

Our judgements are based on an analytical process that includes evaluating the quality of available information, exploring alternative explanations, mitigating biases and using probabilistic language. We use terms such as “we assess” or “we judge” to convey an analytic assessment. We use qualifiers such as “possibly,” “likely,” and “very likely” to convey probability.

Estimative language

The chart below matches estimative language with appropriate percentages. these percentages are not derived via statistical analysis, but are based on logic, available information, prior judgements, and methods that increase the accuracy of estimates.

Long description - Estimative language chart

- 1 to 9% Almost no chance

- 10 to 24% Very unlikely/very improbable

- 25 to 39% Unlikely/improbable

- 40 to 59% Roughly even chance

- 60 to 74% Likely/probably

- 75 to 89% Very likely/very probable

- 90 to 99% Almost certainly

Key judgements

- We assess that financially motivated cybercriminals are the most likely cyber threat to affect the marine transportation sector. We assess that cybercriminals will almost certainly continue to exploit marine transportation and supporting organizations through extortion tied to ransomware, in addition to selling or exploiting stolen personal or proprietary business information. We assess that ransomware is almost certainly the most likely disruptive cyber threat to affect marine transportation operations.

- The marine transportation sector’s importance to Canada’s economic and strategic supply chains makes it a high priority target for state-sponsored cyber threat activity. We assess that state-sponsored cyber threat actors will very likely continue targeting the Canadian marine transportation sector and supporting organizations to steal logistical and operational data that can be leveraged for economic advantage, and to steal intellectual property that can be used to support state commercial, military, and intelligence priorities.

- We assess that the marine transportation sector is a strategic target for disruption or destruction by state-sponsored cyber threat actors. However, we judge that these actors would likely only intentionally disrupt or damage Canadian marine transportation infrastructure in times of crisis or conflict between states.

- We assess that non-state cyber threat actors will very likely continue targeting the Canadian marine transportation sector in connection to international events and conflicts, primarily though distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks and website defacements.

Introduction

The marine transportation sector (MTS) plays a pivotal role in Canada’s economy by supporting the movement of goods and travelers to and from domestic and international markets. Marine transportation and its supporting activities contributed over $8.3 billion to Canada’s gross domestic product in 2022 and accounted for 24% of Canadian merchandise imports and 18% of Canadian merchandise exports in 2023.Footnote 1 Marine transportation is a key method of connection for communities and industries across Canada’s expansive geography and is the sole option for resupply in some northern communities.Footnote 2 The MTS’s importance to Canada makes the cyber security of Canadian ports, vessels, supporting infrastructure, and the organizations that operate them a matter of critical importance for Canada’s national and economic security.

Cyber threat activity against the MTS can have significant consequences. Cyber-enabled fraud and scams are costly for victims,Footnote 3 and disruptive cyber threat activity such as ransomware can interfere with marine transportation operations, implicating safety and causing costly disruptions to supply chains. For example, in 2017, the NotPetya wiper malware affected organizations worldwide, including global shipping company A.P. Møller-Maersk.Footnote 4 Maersk was forced to entirely rebuild the affected computer systems and experienced global operational interruptions. Maersk experienced an estimated $250 to $300 million USD in damages, and unknown additional damages on the part of Maersk customers stemming from supply chain interruptions and shipping delays.Footnote 5

Digitalization is expanding the sector threat surface

The MTS is digitalizing its operations to improve efficiency and address environmental challenges such as decarbonization. Digitalization refers to the incorporation of data-informed decision making, connected technology, and automation throughout the scope of marine transportation operations. Digitalization is supported by the wide deployment of sensors that collect operational and environmental data—for example, smart buoys, video-based container recognition systems, and shipboard sensors—that provide enhanced situational awareness and allow for centralized management over marine transportation operations.Footnote 6 It also involves the adoption of digitally transformed operational technology (OT) and industrial systems within ports and on vessels, such as ship-to-shore cranes and physical access control systems.

Digitalization is expanding the MTS’s threat surface. Increased adoption of connected OT systems provides cyber threat actors more opportunities to exploit those systems to disrupt their functioning, or to use them to gain access to business or OT networks. New methods of connection such as very short aperture terminal satellite Internet connections extend the reach of cyber threat actors to vessels and OT systems even in remote areas. Further, the growing volume of operational and environmental data being collected and shared within and across organizations, and the systems supporting that growth, are valuable targets for commercial or strategic espionage and potential targets for disruption.

Position, navigation and timing systems are vulnerable to interference

The MTS relies on the integrity and availability of various position, navigation and timing (PNT) systems, including the Automatic Identification System (AIS) and the Global Positioning System (GPS). Accurate PNT information is critical for safe vessel navigation and is essential for new technologies such as autonomous vessels and smart port systems. AIS and GPS signals are vulnerable to interference because they typically lack encryption or any mechanism for validating the content or originator of a signal.

Interference with PNT systems falls into 2 categories:

- Signal jamming is a form of denial-of-service attack that prevents a target system from receiving an intended communication by overwhelming the receiver using a malicious signal, making PNT information inaccessible to the victim.

- Signal spoofing is a form of data manipulation that deceives a target system into accepting a malicious signal rather than the intended communication. This can result in incorrect location information being provided to a user, which may cause them to adjust course and potentially navigate into dangerous areas.

There has been an increase in the number of reported PNT interference incidents affecting civilian marine and air transportation in the past several years. Some reported incidents are likely incidental effects of military electronic warfare measures near conflict areas, including around Ukraine. However, PNT interference may also be used to hide criminal maritime activities or support state geopolitical objectives.Footnote 7 For example, in July 2019, the British-flagged Stena Impero was seized by Iran in the Strait of Hormuz for violating Iranian territorial waters. Analysis by security researchers suggests that the Stena Impero may have diverted course into Iranian territorial waters because they were provided spoofed positional information through AIS, possibly to justify seizure of the vessel by Iran.Footnote 8

As the MTS continues to digitalize, the associated threat surface from proprietary information and data being shared with third-party service providers expands.

We assess that medium and high-sophistication threat actors will very likely attempt to exploit third parties to steal sector information, or to gain access to organizations within the sector by exploiting the digital supply chain.

Arrangements where suppliers have remote access to organizational networks, or where they provide a product with consistent data exchange between organizations, increase the opportunities for supplier-based compromise by cyber threat actors.Footnote 9 This may include organizations that provide information technology services such as cloud or managed service providers, software-as-a-service providers, and suppliers for digitally transformed technology.

The threat from cybercriminals

We assess that financially motivated cybercriminals are the most likely cyber threat to affect the MTS. We assess that cybercriminals will almost certainly continue to exploit marine transportation and supporting organizations through extortion tied to ransomware, in addition to selling or exploiting stolen personal or proprietary business information.

The MTS is an attractive target for extortion by cybercriminals because of the economic importance of supply chains and the dependence of its clients on the continuity of shipping operations. Some cybercriminals specifically target organizations such as ports or shipping companies that may be willing to pay large ransoms to recover from disruptions as quickly as possible. However, most cybercriminal activity opportunistically targets organizations regardless of their size by exploiting vulnerable Internet-exposed devices or through bulk phishing or password spraying campaigns.Footnote 10

Top 10 ransomware threats to Canada in 2024 by rank

-

AKIRA

Ransomware-as-a-service: Yes -

PLAY

Ransomware-as-a-service: Yes -

MEDUSA

Ransomware-as-a-service: Yes -

LOCKBIT

Ransomware-as-a-service: Yes -

BLACK BASTA

Ransomware-as-a-service: Yes -

RANSOMHUB

Ransomware-as-a-service: Yes -

CACTUS

Ransomware-as-a-service: Unknown -

CL0P

Ransomware-as-a-service: No -

HUNTERS INTERNATIONAL

Ransomware-as-a-service: Yes -

QILIN

Ransomware-as-a-service: Yes

Cybercriminals are continuously evolving their tactics to increase their ability to extract profit from victim organizations. Illicit marketplaces for cybercrime tools and services reduce the barrier to entry for cybercriminal activity, and the proliferation of prebuilt cyber tools such as ransomware-as-a-service (RaaS) variants increases the impact even low sophistication cybercriminals can have on their victims.Footnote 10 In the RaaS model, a cybercrime group maintains their own version of ransomware and leases it to other cybercriminals in exchange for a portion of ransom payments they receive. In the January to March 2024 period, 8 of the top 10 most impactful ransomware variants by number and severity of incidents were assessed as being RaaS.Footnote 10

Ransomware is the most likely disruptive threat to marine transportation

We assess that ransomware is almost certainly the most likely disruptive cyber threat to affect the MTS.

Ransomware attacks can cause operational disruptions by preventing access to business systems and information, disrupting operational communications within or between organizations, or by preventing operators from accessing or safely operating industrial systems. Although the primary means of extortion against ransomware victims is data or device encryption, cybercriminals frequently use other methods to pressure victims into providing a ransom payment. This includes exfiltrating sensitive files and data prior to deploying the ransomware and threatening to sell the stolen information if payment is not received.Footnote 11

There are several recent examples of ransomware attacks disrupting marine transportation operations. In July 2023, a ransomware attack against the Japanese Port of Nagoya caused the port to entirely stop its container operations for several days.Footnote 12 The Nagoya Harbor Transportation Association disclosed that the attack was conducted with LockBit 3.0, one of the most widely deployed RaaS variants.Footnote 13

Cybercriminals have also targeted organizations that provide managed services and software for clients across the MTS and disrupted the availability of those services. In January 2023, a ransomware attack forced a Norwegian maritime software provider to shut down servers used by their ship management product.Footnote 14 The outage affected 70 of the organization’s clients and approximately 1,000 vessels, with clients only able to access the software’s offline functionalities.Footnote 15 We assess that cybercriminals will very likely continue targeting organizations that provide services to large numbers of clients within the MTS to maximize the effects of their activity and to increase pressure on victims to provide ransom payment.

Significant ransomware attacks against the marine transportation sector

- In July 2021, a ransomware attack against a South African logistics company disrupted operations at container terminals in Durban, Ngqura, Port Elizabeth, and Cape Town. The Durban Port alone accounts for approximately 60% of all South African container traffic and was reduced to 10% of its operational capacity for almost a week.Footnote 16

- In January 2022, a ransomware attack against European oil and gas organizations resulted in disruptions to port-based oil storage and transportation infrastructure, disrupting oil and gas supply chains.Footnote 17

- In March 2023, a ransomware attack against a Dutch shipping company resulted in data related to business contracts and employee personal information being stolen.Footnote 18

- In April 2023, a ransomware attack against a United States (U.S.) shipbuilding company Fincantieri Marinette Marine resulted in short-term production delays and the unauthorized disclosure of personal information for over 16,000 individuals.Footnote 19

Data theft supports additional cybercriminal activity

In addition to directly defrauding or extorting victims, cybercriminals benefit from stealing and exploiting stolen organizational data to conduct further threat activity against the victim organization, its business partners, and employees. For example, stolen information related to organizational devices and networks can be used to plan additional compromises, and information on an organization’s business plans and activities can be used to craft convincing lures for phishing emails against clients and employees. Stolen information may also be sold through dark web forums to other cybercriminals, competitor organizations, or state-sponsored cyber threat actors. In a limited number of cases, cybercriminals have used network access and stolen information to facilitate physical criminal operations such as cargo theft and smuggling.Footnote 20

The threat from state-sponsored cyber actors

The MTS’s importance to Canada’s economic and strategic supply chains makes it a high-priority target for state-sponsored cyber threat activity.

State-sponsored cyber threat actors are capable of highly sophisticated threat activity that is difficult to detect and attribute and may maintain persistence within compromised environments for years before being detected.Footnote 21 State-sponsored threat actors, including from the People’s Republic of China (PRC), Russia, and Iran, have consistently targeted the MTS for espionage, to intimidate or project power against adversaries, and to disrupt adversary commercial and military supply chains.

Espionage for commercial and strategic advantage

We assess that state-sponsored cyber threat actors will very likely continue targeting the Canadian MTS and supporting organizations to steal logistical and operational data that can be leveraged for economic advantage, and to steal intellectual property that can be used to support state commercial, military, and intelligence priorities.

Foreign states can exploit stolen logistical and operational information from the MTS, including data on the movement of goods and people, business development plans, and other forms of proprietary information. This information may provide foreign industry competitive advantage or leveraged for economic or diplomatic advantage over Canada in bilateral relations such as trade negotiations.Footnote 22 Likely targets for state-sponsored commercial espionage include port authorities, port terminal operators, shipping lines, regulators, and organizations involved in the sharing, storage, or analysis of marine transportation data.

Stolen intellectual property and research information from Canada’s robust ship building, marine research, and innovation base can be directly leveraged by foreign states to improve the efficiency and competitiveness of foreign industry or sold to third parties to co-opt the financial gain Canadian organizations would have realized through commercializing their intellectual property. State-sponsored actors have demonstrated a particular interest in intellectual property and research information with a dual-use military application or that would otherwise support foreign state interests, even if the intent of the research is not explicitly military in nature. This may include, for example, research related to the use of drones in marine operations, improving the ability for vessels to operate in arctic conditions, or measuring and predicting environmental changes in the Arctic. Likely targets for state-sponsored espionage targeting intellectual property includes ship builders, research and innovation hubs, and university researchers.

Examples of state-sponsored activity against the marine transportation sector

- In January and February 2018, PRC threat actors stole data from an organization contracted by the U.S. Navy related to submarines and undersea warfare.Footnote 23

- In March 2019, security researchers reported that PRC state-sponsored threat actors targeted over 20 universities worldwide attempting to steal maritime research with military application.Footnote 24

- In March 2023, security researchers attributed malware found in several European commercial cargo shipping companies to PRC advanced persistent threat group Mustang Panda.Footnote 25

Pre-positioning disruptive or destructive cyber capabilities

We assess that the MTS is a strategic target for disruption or destruction by state-sponsored cyber threat actors.Footnote 26

However, we judge that these actors would likely only intentionally disrupt or damage Canadian marine transportation infrastructure in times of crisis and conflict between states. Disruptive or destructive cyber threat activity against the MTS by state-sponsored actors may be used to intimidate and demoralize the public, to disrupt economic and strategic supply chains, or to damage or destroy marine transportation infrastructure. State-sponsored actors pre-position for this activity by identifying and gaining access to Internet-connected OT systems, or IT networks from which they can laterally move to OT systems. Once in the target network, they collect information on assets within the network to identify opportunities for disruptive or destructive action. Likely targets for state-sponsored pre-positioning and disruption include connected OT and infrastructure at major Canadian ports and supply chain bottlenecks, especially those that may be involved in military mobilization.Footnote 27

We assess that state-sponsored cyber threat actors are almost certainly improving their capacity to disrupt or destroy adversary critical infrastructure through active reconnaissance including network intrusion, developing disruptive tools and techniques, and maintaining access against targets and systems of interest.

On February 7, 2024, the Cyber Centre and international partners released a joint advisory about PRC Volt Typhoon state-sponsored cyber threat actors compromising and maintaining access to U.S. critical infrastructure, including within the MTS.Footnote 28 The advisory assesses with high confidence that Volt Typhoon activity has aimed to pre-position cyber capabilities to “enable the disruption of OT functions across multiple critical infrastructure sectors” in the event of conflict. Volt Typhoon activity has been noted by private sector partners as early as May 2023, targeting sectors including manufacturing, government, and marine transportation. Footnote 29

We assess that the direct threat to Canada’s critical infrastructure from PRC state-sponsored threat actors is likely lower than that to U.S. infrastructure. However, given the integration of the Canadian and U.S. economies, malicious activity targeting U.S. infrastructure would likely also affect Canada. For example, disruptions to U.S. ports may result in shipments being diverted to Canadian ports, straining capacity and risking supply chain disruptions.

Foreign ownership

We assess that state-sponsored cyber threat actors are likely to attempt to exploit foreign ownership connections to steal organizational data or attempt to gain network access to Canadian marine transportation organizations.

Some states, including the PRC and Russia, can legally compel their industries to cooperate with state intelligence services.Footnote 30 This creates a threat that some foreign-owned digital service providers could be leveraged to access Canadian customers’ data, to access customer networks, or to deny service to customers to disrupt their operations.Footnote 31

The threat from non-state cyber threat actors

We assess that non-state cyber threat actors will very likely continue targeting the Canadian MTS in connection to international events and conflicts, primarily though DDoS attacks and website defacements.

Ideologically motivated non-state actors, sometimes referred to as hacktivists, have become an increasingly common feature of the cyber threat environment. In 2023, pro-Russia non-state (PRNS) actors were responsible for 2 wide-spread DDoS attack campaigns against Canada intended to undermine Canadian support for Ukraine. These DDoS attacks primarily affected the public facing websites of government and private organizations across the country, including within the MTS and affecting several Canadian ports.Footnote 32 However, DDoS attacks by PRNS actors in September 2023 had additional disruptive effects to airports where check-in kiosks lost connectivity and caused delays. Footnote 33

Distributed denial-of-service attack primer

Volume-based DDoS attacks disrupt access to a target system, often a public website, by flooding the server with requests to the point where it is unable to respond. Volume-based DDoS attacks frequently rely on multiple attacker-controlled systems, often by using botnets, to provide sufficient traffic volumes to degrade the target system.

Slow DDoS attacks use fewer, more complex requests to occupy a server’s resources and prevent legitimate users from accessing it. Slow DDoS attack traffic can be difficult to distinguish from legitimate traffic, making it difficult to detect and mitigate.

Internet Protocol (IP) address range DDoS attacks target the full IP range of a target organization rather than being aimed towards a single server. By targeting the IP range, attackers can affect any of the target’s Internet-facing devices, including gateway devices, public facing web applications, and Internet-based interfaces for OT systems.

Some non-state actors have attempted to maximize the disruptive impact of their DDoS attacks by targeting Internet-exposed IT infrastructure. This activity increases the risk that DDoS attacks will inadvertently affect other Internet-exposed systems and services, including edge devices, web-based applications such as Port Information Management Systems, and Internet-facing interfaces for connected industrial systems.

In May 2024, the Cyber Centre and partners issued a joint advisory warning of PRNS actors targeting Internet-exposed industrial systems. These actors opportunistically identify targets using publicly available scanning tools to search for Internet-exposed systems with vulnerable configurations. For example, they may look for systems that use default or weak passwords and without multi-factor authentication.Footnote 34

We assess that non-state threat actors are very likely to continue developing their capacity to disrupt Internet-exposed industrial systems, and likely that they will attempt to disrupt Internet-exposed industrial systems within Canada.

It is important to note that non-state cyber threat actors may not have the expertise to correctly identify or understand the system they have compromised, may exaggerate claims of disruptive effects, and may entirely fabricate claims that they have compromised or disrupted Internet-exposed OT. False or exaggerated claims can serve to build the reputation of the groups involved and may still have a disruptive effect by causing fear and degrading trust in the system.

Outlook

The cyber security of Canada’s MTS is critical for Canada’s national and economic security. The MTS’s economic and strategic importance to Canada also makes it a compelling target for cyber threat actors with financial, ideological, or disruptive intent. As the sector continues to digitalize its operations and its threat surface grows, cyber threat actors will have additional opportunities to compromise marine transportation organizations and new ways in which to maximize the disruptive or destructive impact of their activities. This threat is compounded by the sectors already complex and interconnected nature, which creates risk that disruptions to key organizations or systems within the MTS will widely affect the safety and continuity of marine transportation operations.

Many cyber threats can be mitigated through awareness and best practices in cyber security and business continuity. The Cyber Centre encourages all critical infrastructure network owners to take appropriate measures to protect your systems against the cyber threats detailed in this assessment.

Please refer to the following online resources for more information and for useful advice and guidance.

General cyber threat information

- An introduction to the cyber threat environment

- National Cyber Threat Assessments

- Protect your organization from malware (ITSAP.00.057)

- Security considerations for critical infrastructure (ITSAP.10.100)

- Preventative security tools (ITSAP.00.058)

- Defending against data exfiltration threats (ITSM.40.110)

Digitalization and connected OT

- Cyber threat bulletin: Cyber threat to operational technology

- Protect your operational technology (ITSAP.00.051)

- Baseline security requirements for network security zones (ITSP.80.022)

- Network security zoning – Design considerations for placement of services within zones (ITSG-38)

- Top 10 IT security actions to protect Internet connected networks and information (ITSM.10.089)

- Satellite communications (ITSAP.80.029)

Supply chain and supplier-based threat

- The cyber threat from supply chains

- Supply chain threats and commercial espionage

- Cyber supply chain: An approach to assessing risk (ITSAP.10.070)

- Protecting your organization from software supply chain threats (ITSM.10.071)

- Cyber supply chain security for small and medium-sized organizations (ITSAP.00.070)

Cybercrime

- Baseline cyber threat assessment: Cybercrime

- Cyber Centre ransomware overview page

- Ransomware: How to prevent and recover (ITSAP.00.099)

- Ransomware playbook (ITSM.00.099)

State-sponsored cyber threats

- Cyber threat bulletin: Cyber Centre urges Canadian critical infrastructure operators to raise awareness and take mitigations against known Russian-backed cyber threat activity

- Joint cyber security advisory on Russian state-sponsored and criminal cyber threats to critical infrastructure

- Cyber threat bulletin: Cyber Centre urges Canadians to be aware of and protect against PRC cyber threat activity

DDoS attacks