About this document

This assessment is intended to inform cybersecurity professionals and the general public about the threat to Canada and Canadians posed by global cybercrime. This assessment will consider cybercrime’s early history, the development of the most significant cybercrime tactics, techniques and procedures (TTPs), and the current (at the time of writing) nature of the global cybercrime threat and its implications for Canada.

Assessment base and methodology

The key judgments in this assessment rely on reporting from multiple sources, both classified and unclassified. The judgments are based on the Canadian Centre for Cyber Security’s (Cyber Centre) knowledge and expertise in cyber security and are further supported by input from the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP).

Defending the Government of Canada’s information systems provides the Cyber Centre with a unique perspective to observe trends in the cyber threat environment, which also informs our assessments. The Communication Security Establishment’s (CSE) foreign intelligence mandate provides us with valuable insight into adversary behaviour in cyberspace. While we must always protect classified sources and methods, we provide the reader with as much justification as possible for our judgments.

Our judgments are based on an analytical process that includes evaluating the quality of available information, exploring alternative explanations, mitigating biases, and using probabilistic language. We use the terms “we assess” or “we judge” to convey an analytic assessment. We use qualifiers such as “possibly,” “likely” and “very likely” to convey probability.

Assessments and analysis in this report are based on information available as of January 12, 2023.

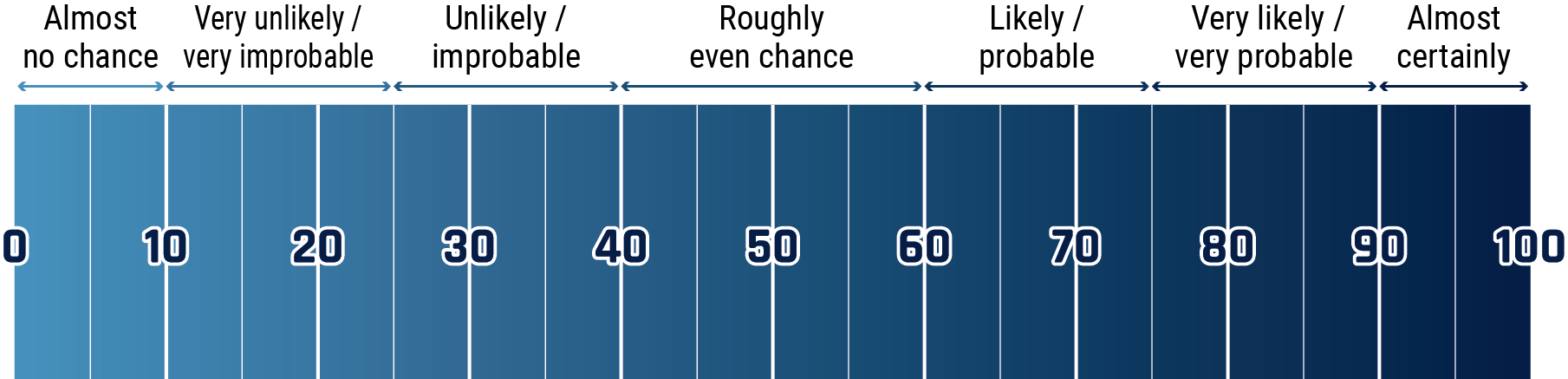

Estimative language

The chart below matches estimative language with approximate percentages. These percentages are not derived via statistical analysis, but are based on logic, available information, prior judgements, and methods that increase the accuracy of estimates.

Long description - Estimative language chart

- 1 to 9% Almost no chance

- 10 to 24% Very unlikely/very improbable

- 25 to 39% Unlikely/improbable

- 40 to 59% Roughly even chance

- 60 to 74% Likely/probably

- 75 to 89% Very likely/very probable

- 90 to 99% Almost certainly

Key judgements

- Ransomware is almost certainly the most disruptive form of cybercrime facing Canada because it is pervasive and can have a serious impact on an organization’s ability to function.

- We assess that organized cybercrime will very likely pose a threat to Canada’s national security and economic prosperity over the next two years. Organized cybercriminal groups can impose significant financial costs on their victims. These groups often have planning and support functions in addition to specialized technical capabilities, such as bespoke malware development.

- We assess that over the next two years, financially motivated cybercriminals will almost certainly continue to target high-value organizations in critical infrastructure sectors in Canada and around the world.

- We assess that Russia and, to a lesser extent, Iran very likely act as cybercrime safe havens from which cybercriminals based within their borders can operate against Western targets.

- We assess that Russian intelligence services and law enforcement almost certainly maintain relationships with cybercriminals and allow them to operate with near impunity. They do so as long as cybercriminals focus their attacks against targets outside of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS). The CIS currently consists of Russia, Belarus, Moldova, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan.

Overview

This assessment looks at the strategic threat to Canada posed by the global cybercrime market. The global cybercrime market is a connected ecosystem that is continuously evolving. It is made up of profit-driven cybercriminals who leverage different TTPs, and operate in regional networks across the globe. This assessment will consider cybercrime’s early history, the development of the most significant cybercrime TTPs, and the current (at the time of writing) nature of the global cybercrime threat and its implications for Canada.

Cybercrime, for the purposes of this baseline threat assessment, refers to “criminal activity that targets a computer, a computer network, or a networked device for profit”. While the RCMP defines cybercrime as “any crime where a cyber element has a substantial role in the commission of a criminal offence”, this baseline threat assessment regards the former, more limited definition. We assess that this category of cybercriminal activity is almost certainly committed by individuals who are primarily financially motivated, regardless of where they are located. Cybercriminals vary widely in sophistication. However, most cybercriminals are opportunistic in their targeting and attempt to compromise targets in bulk using common “spray and pray” tactics such as phishing, social engineering, and exploit kits. Some cybercriminals have also adopted sophisticated targeted attack methodologies in their operations.

We assess that organized cybercrime will very likely pose a threat to Canada’s national security and economic prosperity over the next two years. Cybercriminal groups often have planning and support functions in addition to specialized technical capabilities, such as bespoke malware development.

Some forms of cybercrime, particularly ransomware, have both financial and physical impacts on their victims. For example, some hospitals that were victims of cybercrime indicated the incidents disrupted their ability to care for patients, leading to longer hospital stays for patients, delayed tests or procedures, complications from medical procedures, and, in some cases, increased death rates.Footnote 1

Cybercrime can disrupt the flow of essential goods and services due to its impacts on organizations in an industrial supply chain. For example, in May 2021, a ransomware attack on Colonial Pipeline led to a shutdown of the largest fuel pipelines in the United States (US), leading to price spikes and fuel shortages for millions of Americans.Footnote 2

Cybercriminals are continuously evolving the tactics that let them achieve their primary goal of maximizing profits. Cybercrime has evolved from online theft and credit card fraud to more elaborate ways of extorting victims as the attack surface for cybercriminals has expanded. The increasingly interconnected nature of the modern global economy has provided a growing number of opportunities for cybercriminals as victims’ dependencies on technology continue to grow.

A brief early history of cybercrime

The birth of profit-driven cybercrime

The 1990s marked the beginning of a technical revolution whereby home computers and Internet access became commonplace and humans across the globe were more connected than ever before. The digitization of personal data and commerce in the ’90s created new and novel opportunities for financial prosperity, both licit and illicit, contributing to an emergence of profit-driven cybercrime in a range of countries including the US, Russia, and the People’s Republic of China (PRC).Footnote 3 In fact, each geographical location produced its own brand of cybercrime. The North American cybercrime community is more open and accessible to both cybercriminals and law enforcement, whereas the Russian-speaking community is more closed. For example, Russian forums are generally more closed and often require a vetting process to gain entry.Footnote 4

The dawn of forums and marketplaces

In its early days, cybercrime was a largely informal, recreational cottage industry.Footnote 3 The turn of the millennium brought the introduction of online forums that facilitated the exchange of information and acted as marketplaces. This was the effective birth of the true cybercrime market and the increasingly professional industry that followed.

Today, cybercriminals use highly developed and specialized forums, or dark web marketplaces (see text box), to seek advice and discuss the latest TTPs. Vendors also commonly offer access to internal systems, website accounts, databases, credentials, tools, malware, credit card details, and exploit kits.Footnote 5

Forums have emerged that specifically focus on various aspects of cybercrime. For example, some address the technical aspects of cybercrime, such as malware and botnets. Others specialize in areas like hacking and zero-day vulnerabilities. Still more exist to support click fraud and spam. Some forums focus on trade, while others centre on discussion. Sites for generalists provide a broad range of sub forums on various topics, while specialist boards emphasize core topics like spam.

Certain forums have also been developed to specialize not only by subject, but also by language. While cybercriminals conduct business in many different languages, Russian-language forumsFootnote i have stood alongside English-language ones as the most significant for the global market.Footnote 3 These forums can be thought of as the technical engine rooms of global cybercrime, hosting hackers, coders and those representing them. A key factor of these forums is that they provide a “safe space” to discuss ideas, share information, and coordinate attacks.

Dark web, deep web, and beyond

The dark web is an unindexed segment of the Internet that is only accessible by using specialized software or network proxies such as Tor. Due to the inherently anonymous and privacy-centric nature of the dark web, it facilitates a complex ecosystem of cybercrime, and illicit goods and services trade.

Adjacent to the dark web is the deep web, which is made up of websites and content that are not indexed by search engines. Instant chat platforms play an increasingly critical role in facilitating access to this illicit information.

Pseudo-anonymous discussion forums and vendor marketplaces hosted on the deep and dark web, along with private and public Telegram channels, provide additional platforms by which cybercriminals communicate and circulate sensitive and stolen credential data.

Profit-driven TTP development

The historic development of the global cybercrime market was led by the profit-driven nature of cybercrime. This has similarly influenced the development of cybercrime TTPs to the present day. Financially motivated cybercriminals have continuously chosen targets and deployed tools to maximize their potential profits within their particularly assessed level of risk. TTPs range from credential phishing and stealing funds directly from individual customers to deploying ransomware on large networks and extorting profits from large organizations.

The evolution of phishing

The term “phishing” was first used and recorded in 1996 by a group of hackers who posed as employees of America Online, a then-popular online service provider. They used instant messaging and email to steal users’ passwords and gain access to their accounts. In the early 2000s, phishers turned their attention to online payment systems. For example, in 2003, cybercriminals started registering domain names that were slight variations of legitimate commerce sites, such as eBay and PayPal. They then sent mass mailings asking customers to visit the sites, enter passwords, and update their credit card and other identifying information.

As online social networks proliferated, phishing attacks started harvesting personal data to customize messages to better fool recipients. This gave rise to spear-phishing, whereby cybercriminals send personally tailored messages to more precisely selected sets of recipients to improve their chances of success. It also introduced whaling, a highly customized spear-phishing attack that targets executives or other high-profile recipients with privileged access and authorities. Both techniques are very common, widely successful, and are used by state-sponsored cybercriminals.

Throughout the pandemic, cybercriminals have used COVID-19-related content in phishing campaigns to trick victims into clicking on malicious links and attachments. These in turn distribute information-stealing malware and, to a lesser extent, ransomware on personal computers and mobile devices.Footnote 6 Cybercriminals have also used major events, such as elections and the Russian invasion of Ukraine, as a lure in phishing and malware campaigns.Footnote 7 Today, phishing emails are a common initial access point for ransomware attacks.

Phishing lures

Cybercriminals and fraudsters use tactics to trick victims into providing personal information. These tactics can be referred to as “phishing lures” or “bait”. Common phishing lures leverage themes related to current events (e.g. Ukrainian relief efforts, COVID-19), or make messages appear to be coming from trusted entities to compel victims to click a phishing link and share personal information or download a malicious attachment.

According to Canadian Anti-Fraud Centre (CAFC) victim reporting (January 1, 2022 to January 1, 2023), these are the top sectors and entities being impersonated.ootnote 8

Top 5 most impersonated sectors

- Government (federal, provincial and municipal)

- Delivery agencies

- Retail

- Health

- Finance

Top 5 most impersonated

- Canada Revenue Agency (CRA)

- Canada Post

- Amazon

- UPS

- Netflix

Banking trojans unleashed

A trojan is a type of malicious software that attempts to evade scrutiny by disguising itself as legitimate software. Often, they are designed to steal sensitive information (e.g. login credentials, account numbers, financial information, credit card information, etc.) from users. Banking trojans differ from standard trojans, as they are written for the express purpose of stealing confidential information from victims’ bank accounts and online payment services. They are sophisticated and equipped with man-in-the-browserFootnote ii techniques such as web injections or redirection mechanisms.Footnote 9

With most banks offering online banking by the year 2000, it wasn’t long before cybercriminals found ways to exploit this new attack surface using malware. Cybercriminals realized that targeting customers, particularly customer credentials, was easier than attacking financial systems directly, which motivated the design of the first banking trojans.Footnote 10

Figure 1: Cyber threat tools

Botnet

A network of computers forced to work together on the command of an unauthorized remote user. This network of compromised computers is used to attack other systems.

Repurposed legitimate tools

Some legitimate tools which were designed for use by cyber security professionals to identify security vulnerabilities. These same tools can be used for criminal purposes.

Exploit kit

A type of toolkit used by cybercriminals to attack vulnerabilities in systems so they can distribute malware or perform other malicious activities. Exploit kits are packaged with exploits that can target commonly installed software.

Malware

Malware is malicious software that allows an individual to perform unauthorized tasks on a computer. There are many categories of malware like viruses, spyware, keyloggers, and ransomware.

Commodity malware infections: Precursors to ransomware attacks

Malware such as Emotet and Trickbot that were initially used as banking trojans have morphed into initial access tools for follow-on activity, such as the deployment of ransomware (see Figure 2). Specialized cybercriminals, known as initial access brokers, compromise victims using first-stage malware. Once they gain access, they then sell that access to ransomware operators to deploy data theft and encryption operations.

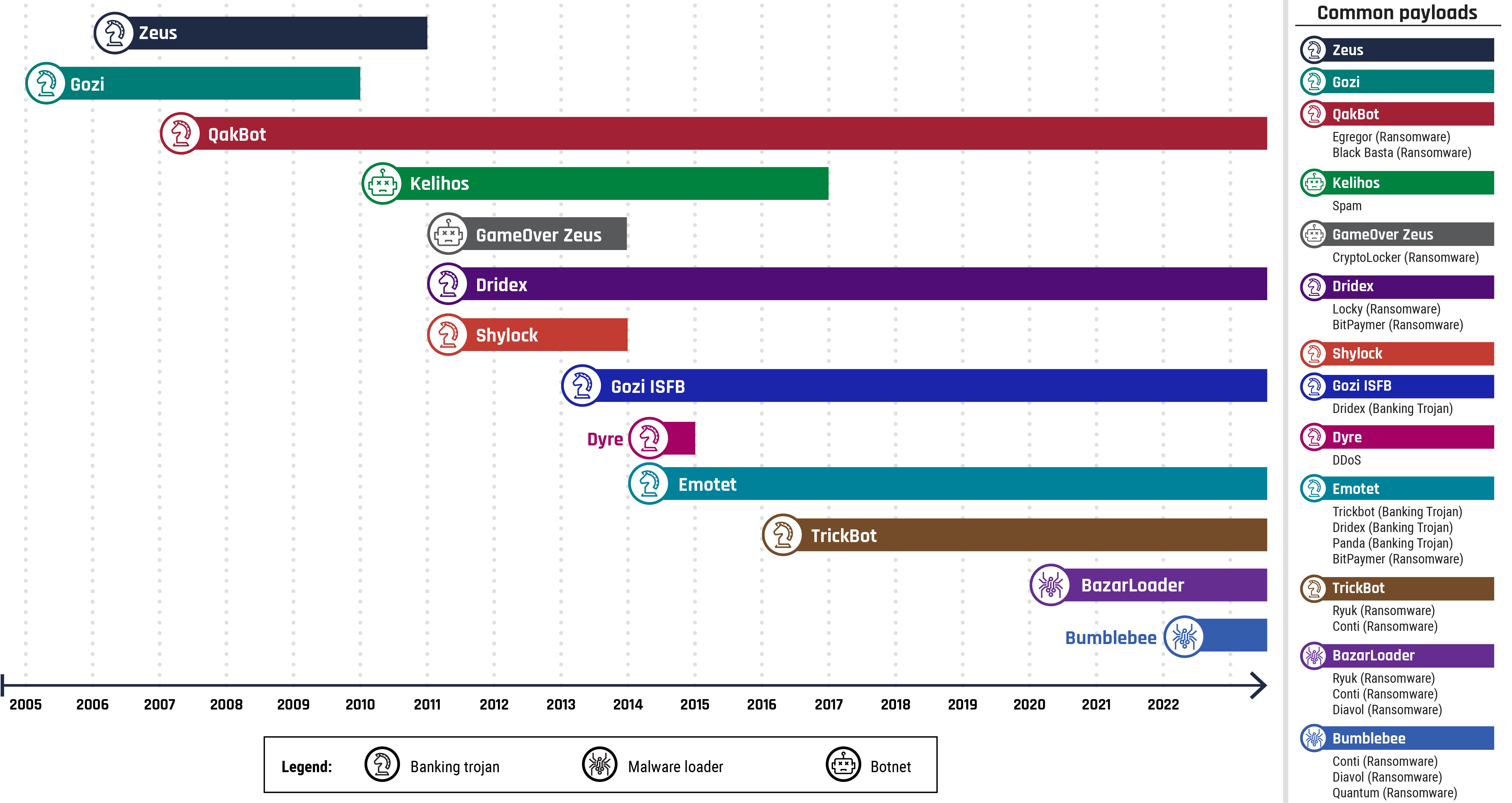

Figure 2: Bots and banking trojans timeline

Long description - Bots and banking trojans timeline

A timeline depicting the use and evolution of certain banking trojans (Zeus, Gozi, QakBot, Gozi ISFB, Dyre, Emotet and Trickbot), malware loaders (BazartLoader and Bumblebee) and botnets (Kelihos and GameOver Zeus) from 2005 to 2022.

Although the original version of Zeus has been largely neutralized by anti-virus software, its source code has been publicly available since 2011, and a number of variants have been developed, including GameOver Zeus, Dridex, and Shylock.

Also known as Ursnif, Gozi is one of the oldest banking trojans. In 2010, and again in 2015, the Gozi source code was leaked, which led to the creation of several different versions of the malware. Although the scope has expanded for many other banking trojans, Gozi continues to primarily target financial institutions.

Emotet has been connected to other banking trojans – including Dridex and Trickbot – and is also used for initial access by ransomware operators. Despite coordinated disruption of its infrastructure by international law enforcement in January of 2021, Emotet once again began spamming malicious emails worldwide as of November 2022.

This shift is representative of a larger transformation across the global cybercrime market. Some cybercriminal enterprises are moving away from mass-scale smash-and-grab attacks, which continue to impact targets with less hardened defences, towards operations that demonstrate more patience and sophistication.

The rise of ransomware

While proof-of-concept ransomware appeared as early as 1989, the first modern campaign is typically attributed to the CryptoLocker ransomware, administered by Russian cybercriminals from September 2013 to May 2014. During this timeframe, according to Federal Bureau of Investigation reports, CryptoLocker infected nearly 500,000 victims, earning as much as CAN$27 million.Footnote 11 From 2014 to 2016, the CryptoLocker model of ransomware (typically emails with malicious attachments distributed through scattershot campaigns) proliferated, emerging mostly from the Russian-speaking cybercrime community.

Automated, scattershot ransomware campaigns continue to target primarily home users and typically spread through cracked software, key generators, and activators.Footnote 12 However, some cybercriminals have moved away from these campaigns towards the manual targeting of large organizations. Although the costs of these operations are higher, threat actors have learned that large organizations are more willing to pay out significantly larger ransoms to recover from disruptions as quickly as possible. Also known as “Big Game Hunting”, targeted ransomware attacks have hit thousands of healthcare and other critical infrastructure (CI) providers, governments, and large businesses. For example, in March 2021, a ransomware attack on Taiwan-based PC manufacturer Acer resulted in the then-highest known ransom demand ever: US$50 million.Footnote 13

Ransomware has become one of the most devastating types of cybercrime, impacting individuals, businesses, and government agencies. Successful cybercriminals in the ransomware industry can rapidly develop and adapt their malware to capitalize on evolving global, national, or regional contexts, and the resultant changes in the vulnerabilities of target organizations. Many of them operate from safe havens, countries which willingly turn a blind eye to, or are unable to interrupt, cybercrime within their borders.

Today, ransomware attacks often use the double extortion tactic. Before encrypting, ransomware actors will exfiltrate files and threaten to leak sensitive information publicly if the ransom is not paid.Footnote 14 Some cybercriminals have moved beyond double extortion tactics to conduct triple or quadruple extortion to maximize the chance their victims will provide payment. These attacks use additional techniques such as threatening an organization’s partners or clients, and distributed denial of service (DDoS).Footnote 15

The global cybercrime market

Like any legal marketplace, the global cybercrime market exists for buyers and sellers to find each other and transact. Unlike a legal marketplace, the global cybercrime market facilitates an array of cybercrime including banking attacks, payment card frauds, identity theft, and ransomware. This market operates mostly in closed and private Internet forums, or private (or encrypted) messaging platforms.

The sophistication of this criminal business model is such that members of these networks can develop specialties, such as writing malicious code or deploying delivery mechanisms for attacks, and rent or sell their tools or services for a portion of the profits rather than performing the attacks themselves.Footnote 16 There are even specialists dedicated to generating payment card authentication numbers and recruiting money mules who launder the proceeds of cybercrime by taking stolen money and goods and turning them into “clean” funds, sometimes without knowing that they are engaging in criminal activity.Footnote 16

An interconnected threat environment

This industrialization of the global cybercrime market increases the potential impact of any cybercrime incident, which might involve several different types of cybercrime before it is discovered. For example, a cybercriminal engaged in the theft of privileged or personal information can profit from this activity by selling that data to criminals, including other cybercriminals, who in turn might use it to gain privileged access and conduct separate activity. Ransomware, in particular, depends on and is enabled by several other forms of cybercriminal activity. Before cybercriminals can deploy ransomware onto victim networks, they must determine their targets, gain access to target systems or networks, and escalate their access privileges to stage their attack.

The ransomware-as-a-service industry

The predominant business model of ransomware is called ransomware-as-a-service (RaaS). RaaS starts with a core group developing the ransomware itself. They then let contractors, known as “affiliates,” use their ransomware to attack victims. The core group often handles the malware development, sets rules for target selection (such as avoiding targeting certain institutions or countries), oversees affiliate activity, carries out negotiations, and accepts ransom payment.

Affiliates are often responsible for gaining access to victim networks, ensuring the collection of data, locating data backups, and deploying the ransomware. Often, affiliates take a large cut of the proceeds, sometimes up to 80%. These are not hard-and-fast rules, and they can change depending on the group.

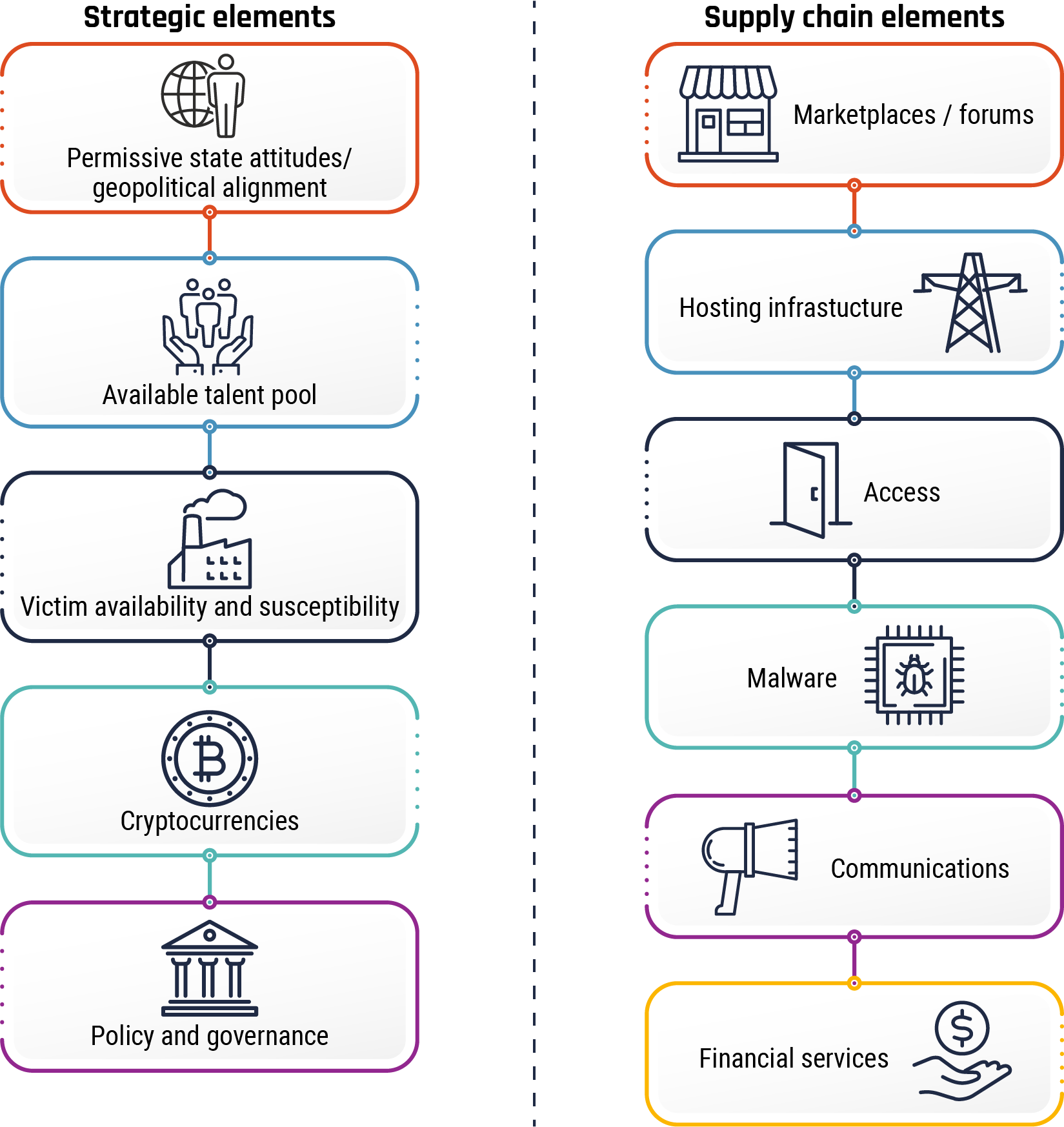

The presence of the certain strategic and supply chain elements is required for RaaS to be a successful business model (see figure 3).

Figure 3: Strategic and supply chain elements of the global cybercrime market

Long description - Strategic and supply chain elements of the global cybercrime market

Strategic elements

- Permissive state attitudes / geopolitical alignment

- Available talent pool

- Victim availability and susceptibility

- Cryptocurrencies

- Policy and governance

Supply chain elements

- Marketplaces / Forums

- Hosting infrastructure

- Access

- Malware

- Communications

- Financial services

Strategic elements of the global cybercrime market

The top-level strategic elements of the global cybercrime market are system-wide elements that modern organized cybercriminal groups and individual cybercriminals require to successfully engage in, and profit from, the business of cybercrime.

- Permissive state attitudes: Cybercriminals often operate in jurisdictions where governments either overtly permit or at least turn a blind eye to cybercrime activities, so long as they only target victims outside their home country.Footnote 17

- Available talent pool: Currently, there is a significant body of technically skilled individuals who are willing to participate in organized criminal activities.Footnote 17

- Victim availability and susceptibility: A large pool of victims needs to be available and have sufficient weaknesses that can be exploited. Organizations and individuals are predominately targeted by cybercriminals in an opportunistic manner.

Cybercriminals perceive that organizations which possess valuable intellectual property or significant personally identifiable information (PII), and organizations that have a low tolerance for downtime are more likely to pay ransoms to prevent the publication of stolen files to restore hijacked systems, or both. - Cryptocurrencies: The emergence of cryptocurrencies has provided new and novel ways to transfer money among victims, cybercriminals, and organized cybercriminal groups. Cryptocurrencies allow cybercriminals to receive and launder large payments in an anonymous or pseudo-anonymous way. By contrast, transferring large ransom payments via a bank or conventional payment service provider would quickly be flagged and traced.

Cryptocurrencies and blockchain technology offer cybercriminals an array of obfuscation tools to efficiently launder illicit funds. They do so by obscuring the flow of value from sender to receiver within and across blockchains. - Policy and governance: Policies regarding cyber security, support for compromised companies, and the legality/permissibility of payments impact the ability or willingness of cybercriminals to conduct attacks. Policy and governance may encompass laws, industry norms, and insurance policies.

The cybercrime supply chain

The cybercrime supply chain refers to the global production and coordination of goods and services that support cybercriminal activity. Like many other businesses, there are many links to the supply chain that hold up cybercrime industries across the world, including the following 6 high-level categories:

- Marketplaces/Forums: Areas in which cybercriminals procure services, share tradecraft, purchase exploits, and/or recruit additional members. These can be open (i.e. anyone can access) or closed, requiring payment, vouching, or some other submission to enter. These marketplaces and forums are typically hosted on the dark web.

- Hosting infrastructure: Cybercriminals require dedicated hosting infrastructure to host their malware, enable communication, and store exfiltrated data. Some hosting infrastructure that is operated by legitimate entities, such as public cloud service providers, is abused for the purpose of engaging in cybercrime activities.

- Access: Cybercriminals require ways to access a victim’s system. This often includes purchasing exploits, zero days, or access directly from an access broker online. An access broker is an individual who specializes in gaining illicit access to an organization.

- Malware: Cybercriminals develop, purchase, or simply use already existing malware to conduct their attacks. A typical cybercrime operation will require several forms of malware throughout its campaign including reconnaissance, intrusion/staging, and exploitation/infection before proceeding to cause specific impact to the victim.

- Communications: Cybercriminals need to be able to acquire the infrastructure and capabilities to communicate, both internally and externally.

- Financial services: This consists of the tools and means that illicit organizations use to conduct their business, including different ways of accepting or transferring money which may include cryptocurrencies or money laundering techniques.

The state-cybercrime nexus

Beyond solely financially motivated cybercrime, the Cyber Centre has observed some cases where state-sponsored cyber threat activity and cybercrime overlap. This activity ranges from state-sponsored threat actors tasking cybercriminals to achieve strategic goals or fulfill intelligence requirements, to state-sponsored cyber actors engaging in cybercrime outside of their official capacity in pursuit of personal profit.

We assess that Russia and, to a lesser extent, Iran very likely act as cyber-crime safe havens from which cybercriminals based within their borders can operate against Western targets with immunity. We further assess that both Russian and Iranian state-sponsored cyber threat actors will use ransomware to obfuscate the origins or intentions of their cyber operations.

Russia

We assess that Russian intelligence services and law enforcement almost certainly maintain relationships with cybercriminals and allow them to operate with near impunity. They do so as long as cybercriminals focus their attacks against targets located outside Russia and CIS countries. Consequently, many of the most sophisticated and prolific cybercriminals are Russia-based. In 2019, the US Department of Justice indicted the leader of the Russia-based EvilCorp cybercriminal group for providing direct assistance to the Russian Federation’s malicious cyber efforts. In April 2021, the US Department of the Treasury stated that the Russian Federal Security Service cultivates and co-opts cybercriminals, including EvilCorp, enabling them to engage in disruptive attacks.

Since the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, several Russian-speaking organized cybercriminal groups have come out publicly either in support of Russia or against its enemies.Footnote 18 Regardless of their motivations, we assess that any escalation in cybercriminal activity against Ukraine, NATO, or the European Union very likely benefits Russia’s strategic goals in Ukraine. For example, in late January 2022, incidents at two subsidiaries of the German oil transportation company Marquard & Bahls and an unrelated ransomware incident at the ports of Amsterdam, Rotterdam, and Antwerp in the Northwest Europe refining hub market caused significant disruption in the delivery of oil products in parts of continental Europe, potentially worsening the existing energy crisis caused by Russia’s then-imminent invasion of Ukraine.Footnote 19

In November 2022, vendor reporting attributed the Prestige ransomware campaign, which targeted organizations in the transportation and related logistics industries in Ukraine and Poland, to Russian military intelligence cyber actors.Footnote 20 In June 2017, cyber threat actors launched destructive cyber attacks masquerading as ransomware, dubbed NotPetya, against Ukraine that quickly proliferated globally, causing over CAN$10 billion in global damages.Footnote 21 Canada has assessed that Russian actors developed the NotPetya ransomware.Footnote 22 AustraliaFootnote 23, New ZealandFootnote 24, the United KingdomFootnote 25, and the USFootnote 26 assess that Russia was directly responsible for the June 2017 attack.

Iran

The relationship between Iran-based cybercriminal groups and Iranian intelligence remains unclear. For example, Iran-based cybercriminals have been observed carrying out ransomware attacks and website defacements against targets in the US, Israel, and the Gulf States in response to major geopolitical events such as the killing of Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corp (IRGC) commander Qassem Soleimani in 2020.Footnote 27 However, while the US, Israel, and the Gulf States are Iran’s main geopolitical rivals, they are also relatively wealthy countries that provide financially motivated Iranian cybercriminals with lucrative targets to attack and exploit.

Despite this uncertainty, we assess that the Iranian state likely tolerates cybercrime activities by Iran-based cybercriminals that align with the state’s strategic and ideological interests, and provides a haven to individuals that have been indicted by foreign law enforcement authorities, possibly recruiting talented cybercriminals to join the intelligence services.Footnote 28 However, Iranian law enforcement authorities almost certainly pursue and punish Iran-based cybercriminals that are suspected of targeting domestic victims.Footnote 29

According to third-party industry reporting, between late July 2020 and early September 2020, Iran’s IRGC operated a state-sponsored ransomware campaign through an Iranian contracting company. It mimicked the TTPs of financially motivated ransomware groups to avoid attribution and maintain plausible deniability.

How cybercrime impacts Canada

Cybercrime continues to be the cyber threat activity that is most likely to affect Canada and its allies, including Canadian organizations of all sizes.

Fraud, scams, and theft in Canada

Fraud and scams are almost certainly the most common form of cybercrime that Canadians will experience over the next two years, as cybercriminals attempt to steal personal, financial, and corporate information via the Internet. Fraud and scams, including malicious cyber threat activity such as phishing, result in significant financial losses. According to the CAFC there were 70,878 reports of fraud in Canada with over $530 million stolen in 2022.Footnote 30 Cybercriminals sell stolen PII, credit card information, and compromised credentials on darknet marketplaces and Telegram channels. In some cases, information stolen during frauds and scams is leveraged to conduct other cybercrime, such as ransomware.

SuperPhish: Business email compromise

One of the most financially damaging forms of cybercrime targeting Canadian organizations is business email compromise (BEC). BEC is a type of email cybercrime scam in which attackers infiltrate a legitimate corporate email account and use the access to send phony invoices of initial contract payments that trick the business or its clients into wiring money to cybercriminals when they think they’re just paying their bills.Footnote 31

BEC attacks, many of which originate in West Africa and specifically Nigeria, are historically less technical. They rely more on social engineering, the art of creating a compelling narrative that tricks victims into taking actions against their own interests, making them also a sophisticated endeavour to complete successfully.Footnote 32

Ransomware in Canada

We assess that ransomware is almost certainly the most disruptive form of cybercrime that Canadians face and has significant impacts beyond the financial cost of the ransom itself. Cyber security reporting indicates that ransom payments have increased since 2020, likely driven in part by increasingly significant demands against larger organizations. The emergence of cyber insurance policies which cover ransomware payments may have implications for the prevalence of ransomware in Canada.

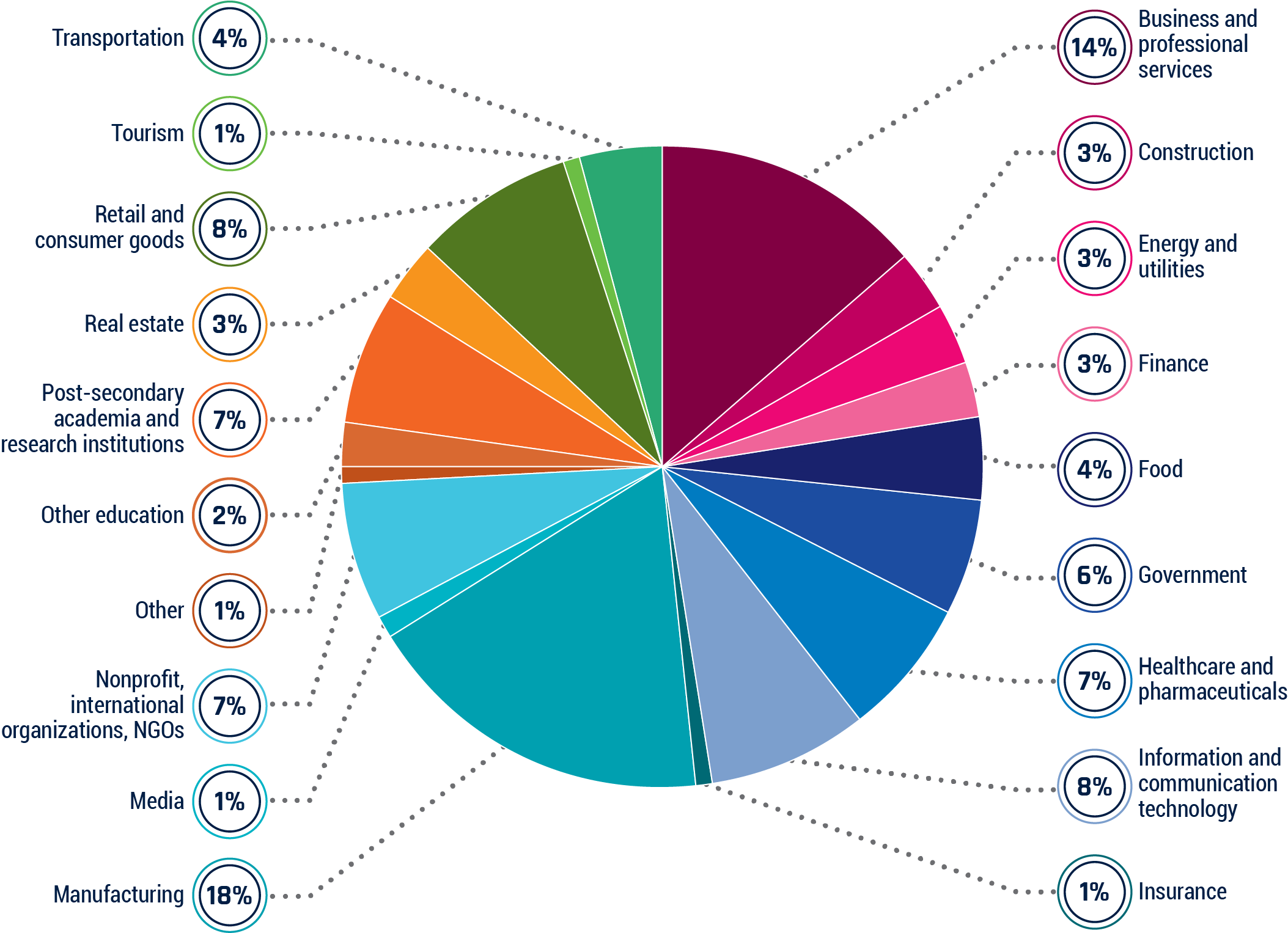

Figure 4: Canadian victims of ransomware in 2022 (by sector)

Ransomware has victimized a wide assortment of Canadian organizations with no discernable pattern based on sector.

Long description - Canadian victims of ransomware in 2022 (by sector)

Canadian victims of ransomware, by sector, from January 1, 2022 to December 31, 2022.Footnote 33

- Business and professional services 14%

- Construction 3%

- Energy and utilities 3%

- Finance 3%

- Food 4%

- Government 6%

- Healthcare and pharmaceuticals 7%

- Information and communication technology 8%

- Insurance 1%

- Manufacturing 18%

- Media 1%

- Non-profit, international organizations, NGOs 7%

- Other 1%

- Other education 2%

- Post-secondary academia and research institutions 7%

- Real estate 3%

- Retail and consumer goods 8%

- Tourism 1%

- Transportation 4%

The value of the ransom paid often represents only a portion of the total cost to the organization, which can also include lost value associated with downtime, lost value of unrecoverable data, costs of repairing systems, and reputational damage from downtime or leaked information associated with the ransomware event. Many ransomware operators use “double extortion” tactics in which they both encrypt victim systems and threaten to publish or sell stolen victim data.

Paying a ransom demand does not guarantee that a victim’s systems will be restored, that they will not be targeted again in the future, or even that exfiltrated data will be deleted by the cybercriminal.Footnote 34 One survey of Canadian businesses found that only 42% of organizations who paid the ransom had their data completely restored.Footnote 14 Further, some ransomware operators retain backdoor access to victim networks following ransom payment.Footnote 35 At least one ransomware platform has generated false evidence to reassure a victim that their stolen sensitive information has been deleted from the attacker’s servers.Footnote 36

In one case, a victim of Conti ransomware paid the ransom demand after initially falling victim. Later, a second attempt at extortion occurred via an affiliate group, where no encryption of the data occurred, but sensitive data had been stolen. Most notable is that the second time the company was victimized, the cybercriminal used the same Cobalt Strike backdoor that was set up during the initial ransomware attack.Footnote 35

Ransomware affecting Canada

The Cyber Centre maintains a database of ransomware incidents affecting Canadian victims. Based on incident data from January 1, 2022 to December 31, 2022, the top 10 ransomware threats to Canada are:Footnote 33

- LockBit

- Conti

- BlackCat/ALPHV

- Black Basta

- Karakurt

- Quantum

- Vice Society

- Hive

- Royal

- AvosLocker

Most of these ransomware variants are maintained by financially motivated, Russian-speaking cybercriminals based in CIS countries.

Big game hunting

We assess that over the next two years, financially motivated cybercriminals will almost certainly continue to target high-value organizations in critical infrastructure sectors in Canada and around the world.

Although business email compromise is very likely more common and costlier than ransomware to victims, we assess that ransomware is almost certainly the main cybercrime threat to the integrity of systems, facilities and technologies, and the supply of products and services essential to the well-being of Canadians and the Government of Canada.

CI is a particularly attractive target for ransomware. CI operators are perceived by cybercriminals to be more willing to pay significant ransoms to limit or avoid physical disruption and follow-on impacts to their customers. Two ransomware incidents in May 2021 against Colonial Pipeline and JBS Foods in the United States alone resulted in multimillion-dollar payouts for cybercriminals in addition to significant disruptions to fuel and food supply chains.Footnote 37

Five months later in October 2021, Canada fell victim to a ransomware attack on a healthcare system in the province of Newfoundland and Labrador. Hive ransomware group was responsible for the attack that caused an IT systems outage,Footnote 38 affecting more than one in every 10 people in the province and incurring just under $16 million in damages.Footnote 39

Once again, the Canadian healthcare sector was disrupted in December 2022 when SickKids hospital in Toronto was attacked by a “partner” of LockBit ransomware group.Footnote 40 While the impact of the attack on patients and families was minimal, some patients did experience diagnostic or treatment delays.Footnote 41 Despite a public apology from LockBit and an offer to share the decryptor with the hospital, this attack on the country’s largest paediatric hospital is representative of the large-scale impact that ransomware groups such as LockBit can have on Canadian CI.

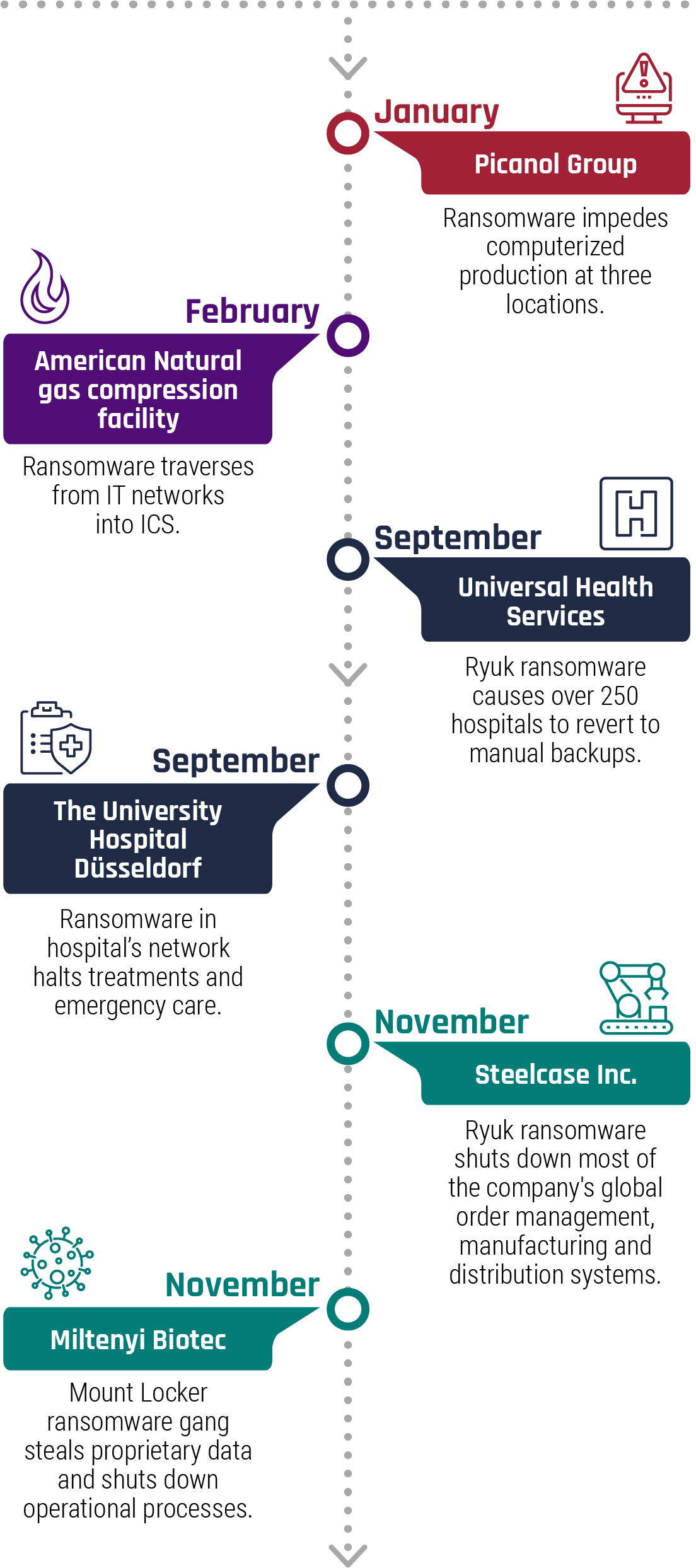

Figure 5: Cybercrime incidents impacting operational technology in 2020

Long description - Cybercrime incidents impacting operational technology in 2020

| Date | Lead | Description |

|---|---|---|

| January | Picanol Group | Ransomware impedes computerized production at three locations. |

| February | American Natural Gas Compression Facility | Ransomware traverses from IT networks into ICS. |

| September | Universal Health Services | Ryuk ransomware causes over 250 hospitals to revert to manual backups. |

| September | The University Hospital Düsseldorf | Ransomware in hospital’s network halts treatments and emergency care. |

| November | Steelcase Inc. | Ryuk ransomware shuts down most of the company's global order management, manufacturing and distribution systems. |

| November | Miltenyi Biotec | Mount Locker ransomware gang steals proprietary data and shuts down operational processes. |

We assess that organized cybercriminal groups will almost certainly continue to target CI providers, including organizations in Canada, in medium-sophistication attacks to try to extract ransom, steal intellectual property and proprietary business information, and obtain personal data about customers.

Cybercriminal activity has the potential to disrupt operations and critical delivery of products by limiting a company’s access to essential business data in the IT network or preventing safe control of industrial processes in the operational technology (OT) network. The disruption or sabotage of OT systems in Canadian CI poses a costly threat to owner-operators of large OT assets and could conceivably jeopardize national security, public and environmental safety, and the economy.

Targeting supply chains and MSPs

We assess that cybercriminals are likely to continue compromising Managed Service Providers (MSPs) (companies that host and manage their clients’ IT resources) and software supply chains to maximize the number of potential victims and profits per compromise. Cybercriminals conducting operations against these types of targets are financially motivated and either seek to exfiltrate commercially valuable information for sale, extort victims through the deployment of ransomware, or deploy cryptojackers (malware that “mines” cryptocurrency using the resources of an infected device).Footnote 42

Cybercriminal supply chain compromises are particularly concerning given the lack of discrimination in their targeting. Supply chain compromises have the potential to expose a wide cross-section of organizations to business disruptions, including elements of critical infrastructure such as schools, hospitals, utilities, and other typical Big Game Hunting targets.

For example, in July 2021, Russia-based ransomware actors compromised and spread ransomware via Kaseya’s Virtual System Administrator service, a system used by MSPs to manage their clients’ networks. Cybercriminals were able to distribute the ransomware to approximately 60 MSPs and 1,500 of their clients from across North America, Europe, Australia, and New Zealand.Footnote 43 After a few days of demanding ransoms from individual victims, the cybercriminals reportedly demanded an extremely high ransom of US$70 million in Bitcoin to decrypt the files of all affected organizations.Footnote 44

Outlook

Over the next two years, we assess that cybercrime activity in Canada will very likely increase. So long as cybercriminals can extract financial profit from Canadian victims, they will almost certainly continue to mount campaigns against Canadian organizations and individuals. Moreover, cybercriminals continue to show resilience and an ability to innovate their business model to remain profitable.

To this end, cybercriminals will continue to evolve new TTPs, including targeting more small- and medium-sized organizations, in order to avoid attention-grabbing higher profile attacks. Cybercriminals, in our judgment, will also very likely adapt to disruptive geopolitical events, such as the Russian invasion in Ukraine. For example, the international sanctions on Russia’s banking system, along with recent international law enforcement actions against cybercrime forums and measures taken by the Russian government to control its Internet infrastructure more tightly, has prompted Russia-based cybercriminals to pursue workarounds to transfer funds between Russia and other countries, either through novel means or by recalibrating existing cash-out methods.Footnote 45

The prevailing model of RaaS has demonstrated its sophistication and resilience, even in the face of heightened international scrutiny and law enforcement action. For example, DarkSide, the ransomware organized cybercriminal group responsible for the Colonial Pipeline disruption, rebranded into BlackMatter and later ALPHV following increased scrutiny from Western law enforcement.Footnote 46 Over the next two years, we assess that cybercrime will very likely remain a national security concern for Canada.