Table of contents

- About this document

- Message from the Head of the Cyber Centre

- Key judgements

- Canada’s water sector

- The threat from cybercriminals

- The state-sponsored cyber threat to water systems

- Non-state cyber actors: A growing threat

- Outlook: What this means for the Canadian Water Sector

- Mitigation

- Additional resources

- References

About this document

Audience

This report is part of a series of cyber threat assessments focused on Canada’s critical infrastructure. It is intended for leaders of organizations in the water sector, cyber security professionals with a water or wastewater asset to protect, and the general reader with an interest in the cyber security of critical infrastructure. For guidance on technical mitigation of these threats, see the Mitigation section or contact the Canadian Centre for Cyber Security (the Cyber Centre).

This assessment is Unclassified/TLP:CLEAR. TLP:CLEAR is used when information carries minimal or no foreseeable risk of misuse, in accordance with applicable rules and procedures for public release. Subject to standard copyright rules, TLP:CLEAR information may be shared without restriction. For more information, see Traffic Light Protocol.

Contact

For follow-up questions or issues, contact the Cyber Centre at contact@cyber.gc.ca.

Assessment base and methodology

The key judgements in this assessment rely on reporting from multiple sources, both classified and unclassified. The judgements are based on the knowledge and expertise in cyber security of the Cyber Centre. Defending the Government of Canada’s information systems provides the Cyber Centre with a unique perspective to observe trends in the cyber threat environment, which also informs our assessments. The Communications Security Establishment Canada’s foreign intelligence mandate provides us with valuable insight into adversary behaviour in cyberspace. While we must always protect classified sources and methods, we provide the reader with as much justification as possible for our judgements.

Our judgements are based on an analytical process that includes evaluating the quality of available information, exploring alternative explanations, mitigating biases and using probabilistic language. We use terms such as “we assess” or “we judge” to convey an analytic assessment. We use qualifiers such as “possibly”, “likely” and “very likely” to convey probability.

The assessments and analysis are based on information available as of May 31, 2025.

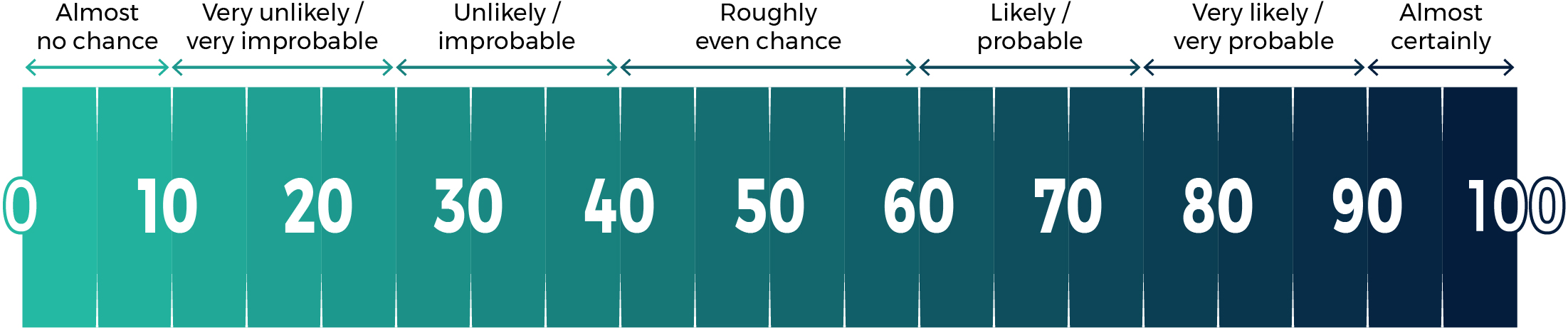

Estimative language

Long description - Estimative language chart

- 1 to 9% Almost no chance

- 10 to 24% Very unlikely/Very Improbable

- 25 to 39% Unlikely/Improbable

- 40 to 59% Roughly even chance

- 60 to 74% Likely/probably

- 75 to 89% Very likely/very probable

- 90 to 100% Almost certainly

Message from the Head of the Cyber Centre

I spend a lot of time looking at threats most people never see. They are quiet, often hidden, yet capable of real-world consequences. Among the most critical are the cyber threats facing Canada’s water and wastewater systems. These systems are the backbone of modern life, yet they’re often out of sight and out of mind. When they function, no one notices. When they fail, everyone does.

This assessment is meant to bring clarity to a topic that can feel abstract or overly technical. Cyber threats to water infrastructure are growing, evolving quickly, and can affect every community in Canada. You don’t need to be an engineer or a cyber security expert to understand why this matters. Clean water is essential, and the systems that deliver it are now largely digital – meaning they are vulnerable to the same kinds of cyber threats that target businesses and governments around the world.

We’ve seen an unmistakable shift in recent years. Cybercriminals are more sophisticated, state-sponsored actors are more willing to target essential services, and disruptive tools are easier to access. Water systems now face a threat landscape they were never designed to withstand.

Whether you’re a critical infrastructure executive, an elected official, or a policymaker, I want to emphasize that cyber security for water systems is not just a technical issue, it is a public safety issue, an economic stability issue, and ultimately a public trust issue. Leadership matters. The choices you make about investment, governance, and preparedness will determine our collective resilience in the years ahead.

But this is not a message of alarm; it is a message of readiness. Across Canada, utilities, municipalities, and provincial and territorial partners have shown a strong commitment to improving their cyber resilience. What’s needed now is a clear-eyed analysis of the cyber threats facing our water systems in Canada. That’s what this assessment provides.

My hope is that it empowers decision-makers to act confidently, ask the right questions, and support the people who keep these systems running. Cyber threats aren’t going away, but with awareness and a steady commitment to resilience, we can stay ahead of them.

Sincerely,

Rajiv Gupta, Head of the Canadian Centre for Cyber Security

Key judgements

- We assess that operational technology (OT) networks that monitor and control physical processes are very likely the primary target for actors seeking to disrupt water systems.

- We assess that financially motivated cybercriminals are the most likely cyber threat to affect water systems. We assess that cybercriminals will almost certainly continue to exploit water sector organizations and systems through extortion tied to ransomware, exploiting stolen information, and business email compromise (BEC). We assess that ransomware is almost certainly the most significant cyber threat to the reliable supply of water in Canada due to the potential impacts against OT systems.

- We assess that water systems are almost certainly a strategic target for state-sponsored actors to project power through disruptive or destructive cyber threat activity. We assess that state-sponsored actors have almost certainly developed pre-positioned access to Canadian water systems. However, we judge that these actors would likely only disrupt those water systems in times of crisis or conflict between states.

- Non-state cyber actors are a growing threat to Canada’s critical infrastructure (CI). We assess that non-state actors will very likely continue to opportunistically compromise and disrupt Internet-exposed water system OT within Canada, especially in connection to major geopolitical events.

Canada’s water sector

Good public and environmental health depend on access to clean water.Footnote 1 Drinking water, stormwater and wastewater treatment systems (collectively: water systems) have many important economic, environmental, and safety uses. A loss of water does not just affect residents but also can have effects on other critical infrastructure. For example, in 2024, water main breaks in Calgary and Montreal resulted in cascading impacts on other systems, including hospitals, fire prevention and universities.Footnote 2 For these reasons and others, our water systems are considered part of Canada’s critical infrastructure (Figure 1).Footnote 3 Any disruption in the water system is not only a threat to public health and safety, but also a threat to public confidence, the environment and the economy.Footnote 4 As a result, the cyber security of our water systems is vital to Canada’s national security.

Critical infrastructure refers to the processes, systems, facilities, technologies, networks, assets and services essential to the health, safety, security or economic well-being of Canadians and the effective functioning of government.

Long description - Figure 1: Critical infrastructure

Icons representing the 10 critical infrastructure sectors in Canada- Energy and utilities

- Finance

- Food

- Health

- Government

- Safety

- Water

- Transportation

- Information and communication technology

- Manufacturing

The threat surface of Canada’s water systems

A water system generally includes the services and infrastructure to safely and reliably obtain, store, filter and distribute potable water, divert runoff and floodwater as well as remove, collect and treat wastewater. Canada has thousands of water systems that vary greatly in size. A small number of large water utilities serve major urban areas while international organizations manage shared systems. Meanwhile, many small systems are owned and operated by municipalities, other levels of government, Indigenous communities, private sector companies and individual citizens.Footnote 5

Water systems operate in a variety of ways. Many are completely manual or even passive systems that require little to no active management, including most small water supplies and stormwater systems. Large urban water systems, in contrast, are usually geographically dispersed, industrial systems operated from a digital control environment. These include many remotely managed OT devices integrated into dams, pumping stations, and treatment facilities. These systems also extend into a web of connected suppliers of digital products and services.

Many of these water systems are managed out of municipal or community offices and are exposed to all the cyber threats encountered by public-facing organizations. The more internet-connected assets an organization has, the larger the threat surface. A larger threat surface implies an increase in the cyber threat the organization faces.Footnote 6 In addition to increasing internet connectivity, most water systems are operated by small public sector organizations and frequently face challenges that can negatively influence cyber security, including low financial resources, aging physical and digital infrastructure and a shortage of cyber security expertise.Footnote 7

The role of operational technology in our water systems

Operators use industrial OT including supervisory control and data acquisition (SCADA) and industrial Internet of things (IIoT) devices to manage large water systems and address issues like population growth, outdated infrastructure and declining revenue.Footnote 8 These systems are used to control water system equipment like dam gates, valves and pumps and to monitor sensors such as chemical detectors and flowrate monitors. The OT in water systems is continually evolving and is increasingly managed through digital devices with embedded computing and communications abilities.Footnote 9 This process, called digital transformation or digitalization, has allowed OT asset operators like those in the water sector to connect their OT devices to operating centres, corporate networks and, increasingly, directly to the internet. A 2021 survey counted over 60,000 OT-related network interfaces in Canada.Footnote 10 In 2023, a similar survey conducted on internet-connected devices associated mainly with water systems in the U.S. and UK found a relatively low level of basic cyber hygiene. Almost half of the devices could be manipulated without any authentication required.Footnote 11

Unfortunately, the management efficiency and savings gained from connecting digitally transformed OT also exposes the water system to cyber threats.Footnote 10 For example, in early 2000, an employee was fired from a company providing services to Maroochy Water Services in Queensland, Australia. The individual retained remote access to the network of OT devices in the pumping stations of the wastewater treatment system.Footnote 12 He used this access to issue malicious commands to the OT devices that ultimately caused nearly a million litres of raw sewage to be discharged into local parks and rivers, causing severe environmental harm, according to officials.Footnote 13 This was the first example of a remote access in a public water system being used to disrupt or sabotage OT systems, and illustrates the potential for cyber threats to jeopardize public and environmental safety and the local economy.Footnote 10 We assess that operational technology (OT) networks that monitor and control physical processes are very likely the primary target for actors seeking to disrupt water systems.

On the rise: Cyber threats to supply chains

Water system utilities often depend on a diverse supply chain of digital products and services to operate, maintain and modernize their OT assets. The supply chain for these products and services includes manufacturers, vendors, integrators, contractors and service providers. Water system OT’s dependency on the supply chain is a critical vulnerability that gives cyber actors inside information on and opportunities for access to otherwise protected OT systems.

Cyber threat actors target organizations’ digital supply chains to collect business and contextual information for use in social engineering attacks or to collect organizational network and system information to support future cyber attacks. Activity against the digital supply chain can also be an indirect route to gain access to the target organization’s networks in situations where there is continuous information transfer, for example software updates, or remote network access connections between the organization and its suppliers. In late 2019, a sophisticated cyber threat actor compromised the software-as-a-service provider, SolarWinds. The actors, attributed to Russia’s intelligence services, used their access to SolarWinds’ development environment to embed malicious code into a software update. The compromised update provided the actors access to thousands of client networks worldwide, including over 100 in Canada.Footnote 14

Publicly available cyber tools are increasing the volume and effectiveness of cyber threat activity

We assess it almost certain that cyber threat actors are increasingly using publicly available cyber tools to gain and maintain access to CI networks, making it easier for threat actors of all levels of sophistication to target water sector OT. The wide availability of these tools, including legitimate penetration testing tools like Cobalt Strike, has lowered the barrier to entry to cyber threat activity and increased the capacity for cyber threat actors to gain, maintain, and expand access to target systems.Footnote 15

The proliferation of publicly available cyber tools has advantages for sophisticated cyber threat actors as well. Advanced cyber threat actors often use a combination of publicly available tools and living-off-the-land (LOTL) techniques when possible and bespoke malware when necessary. For example, People’s Republic of China (PRC) threat actors Volt Typhoon, Flax Typhoon and APT40 commonly use a mixed toolset and likely maintain an extensive catalog of open source and custom malware.Footnote 16 LOTL techniques exclusively rely on legitimate tools and processes already present in the victim’s environment, for example Windows PowerShell or Windows Management Instrumentation, to carry out malicious activity.Footnote 17 These techniques allow threat actors to blend their malicious activity in with normal network activity. By using generic publicly available tools and LOTL techniques, sophisticated actors limit the distinct signature they leave on a target’s network, making detecting cyber threat activity and attributing the source of that activity even more challenging.Footnote 18

The threat from cybercriminals

We assess that financially motivated cybercriminals are the most likely cyber threat to affect water systems. We assess that cybercriminals will almost certainly continue to exploit water sector organizations and systems through extortion tied to ransomware, exploiting stolen information and business email compromise (BEC). BEC is a type of fraud that uses compromised email accounts to trick people into transferring money or sensitive information to attacker-controlled accounts, while ransomware is malware that encrypts data or locks devices to extort a target organization for ransom payment.Footnote 19 Although BEC is likely more common and more costly than ransomware to victims, ransomware can disrupt operations such as the delivery of safe drinking water through loss of visibility or control over important industrial processes.Footnote 20 We assess that ransomware is almost certainly the most significant cyber threat to the reliable supply of water in Canada due to the potential impacts against OT systems. Cybercriminals are aware that the disruption of critical products and services increases the pressure on an organization to pay ransom.Footnote 21 For example, ransomware attacks disrupted water treatment systems in California, Maine and Nevada in 2021, and in Kansas in 2024, forcing system operators to manually operate their OT systems to maintain service.Footnote 22

Ransomware incidents are becoming more complex and costly to remediate

We assess that ransomware attacks against CI organizations, including those in the water sector, are almost certainly becoming more frequent as well as more costly and complex to remediate. The number of observed ransomware incidents has increased across sectors from 2021 to 2024. The size of ransom demands, cost of recovery, and the sophistication and complexity of tactics being used by cybercriminals have also increased.Footnote 23 These trends are driven by the proliferation of ransomware-as-a-service (RaaS) variants, the cybercrime-as-a-service (CaaS) ecosystem, and the increased use of multiple extortion methods.Footnote 24

Cybercriminals have widely adopted the practice of stealing and threatening to leak their victims’ sensitive data as either a supplement to traditional encryption-based extortion or as the primary lever for extortion. In early 2023, the cybercriminal group CL0P exploited a vulnerability in MOVEit Transfer, a file transfer tool made by Progress Software. CL0P’s attacks were far-reaching, allowing them to steal information from government, public and business groups all over the world, including the water utility files of Queens Municipality in Nova Scotia.Footnote 25 In early 2024, 2 different cybercriminal groups conducted ransomware attacks against water sector organizations in North America and the United Kingdom. The groups disrupted IT systems and leaked stolen data including business data and personal information.Footnote 26

Cybercrime marketplaces provide specialized services and increase impacts against victims

Cybercrime is continuously evolving to maximize profits and increase the payouts extracted from targets.Footnote 27 The CaaS ecosystem allows for specialization and division of labour among cybercriminal groups. This allows cybercriminals to access a range of services including network access brokering, access to RaaS variants and money laundering. Access brokers opportunistically collect network accesses into victim organizations and sell them to other cybercriminals. Those cybercriminals then conduct reconnaissance and use social engineering to determine which targets to deploy ransomware against. These decisions are often based on which organizations are most likely and/or able to pay a ransom.Footnote 19Footnote 27 We assess that the CaaS ecosystem is almost certainly increasing the number of actors participating in cybercrime by enabling less technically sophisticated actors to carry out cyber threat activity.

The state-sponsored cyber threat to water systems

We assess that water systems are almost certainly a strategic target for state-sponsored actors to project power through disruptive or destructive cyber threat activity. State-sponsored actors pre-position for this activity by identifying and gaining access to Internet-connected OT systems or IT networks from which they can laterally move to OT systems. Once in the target network, they collect information on assets within the network to identify opportunities for disruptive or destructive action. For example, this could mean causing water tanks to overflow or changing the chemical balance of water treatment processes. We assess that state-sponsored cyber threat actors have almost certainly developed pre-positioned access to Canadian water systems. However, we judge that these actors would likely only disrupt those water systems in times of crisis or conflict between states.

State-sponsored cyber threat actors have targeted water sector organizations and systems globally for both espionage and disruption or destruction. In an early example of state-sponsored cyber activity in water system OT, in 2013, Iranian actors gained access to the SCADA system of a small dam in New York State. This access allowed them to obtain information regarding the dam’s status and the ability to operate the sluice gates of the dam, which could affect water levels and flow rates in the watershed. The system was under maintenance at the time of the compromise, so the actors did not obtain actual access to the dam’s physical controls.Footnote 28

In 2023, an Iranian Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) cyber unit acting under the non-state actor persona “CyberAv3ngers” compromised the Municipal Water Authority of Aliquippa, Pennsylvania. The CyberAv3ngers exploited a publicly exposed Unitronics Vision Series OT device with default passwords and defaced the system’s interface with an anti-Israel message. This activity was part of a broader campaign targeting commonly used Israeli-made OT devices, likely to undermine Western support for Israel. Tampering with the controller's user interface implies a level of access that would allow full access to the device settings, as well as potential access to other devices on the network. It is not known if cyber activity beyond defacement was planned or carried out.Footnote 29

In 2023 and 2024, the Cyber Centre and its partners published the following joint advisories to warn critical infrastructure organizations of a PRC state-sponsored cyber group known as Volt Typhoon:

- Joint guidance for executives and leaders of critical infrastructure organizations on protecting infrastructure and essential functions against PRC cyber activity

- CSE and its Canadian Centre for Cyber Security release advisory on People's Republic of China state-sponsored cyber threat

- Joint advisory on PRC state-sponsored actors compromising and maintaining persistent access to U.S. critical infrastructure and joint guidance on identifying and mitigating living off the land

Volt Typhoon activity has been observed since mid-2021 targeting the water sector and communication, transportation and energy organizations.Footnote 30 Volt Typhoon strategically selects targets, pre-positioning itself in organizations that, if disrupted, would restrict military mobilization efforts and cause societal chaos. While the Cyber Center assesses that the direct threat to Canada’s CI by Volt Typhoon is less than that to the U.S., it is not insignificant, especially for Canadian organizations that rely on cross-border trade, infrastructure or operations. In addition, the likelihood of a cyber attack impacting Canada’s CI is higher than it otherwise might be because of the connections between US and Canadian infrastructure.

Non-state cyber actors: A growing threat

The Cyber Centre warned in our National Cyber Threat Assessment 2025-2026 that non-state cyber actors are a growing threat to Canada’s critical infrastructure. The wide proliferation of easy-to-use disruptive cyber capabilities has contributed to the emergence of a large eco-system of hacktivists and other non-state actors who opportunistically target Canada and its allies for a variety of reasons. Often, this activity is intended to intimidate or coerce its targets or to influence Canadian public opinion or policy decisions related to geopolitical events outside Canada.

Non-state threat activity frequently targets public-facing websites through techniques including distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) and defacement attacks. However, some non-state actors have adopted the practice of targeting and attempting to disrupt vulnerable Internet-connected OT systems. Although non-state actors have targeted OT across CI sectors, a notable proportion of this activity has implicated water system OT.

In May 2024, the Cyber Centre and partners issued a joint advisory warning of pro-Russia non-state actors targeting Internet-exposed industrial systems. These actors opportunistically identify targets using publicly available scanning tools to search for internet-exposed systems with vulnerable configurations, such as using default or weak passwords or not using multi-factor authentication.Footnote 31 After gaining access to these systems, they attempt to disrupt the system by defacing system interfaces, making configuration changes, and manipulating system controls. This activity can result in OT systems operating in unintended ways, operational disruptions, and, potentially, physical damage to the systems. For example, in early 2024, a non-state actor compromised the OT systems controlling water storage tanks in the towns of Abernathy and Muleshoe, Texas and caused a tank overflow resulting in the loss of roughly 100,000 litres of water.Footnote 32

The Cyber Centre is aware of several instances of non-state actors similarly attempting to disrupt internet-exposed OT systems in Canada, including within water systems. We assess that non-state actors will very likely continue to opportunistically compromise and disrupt internet-exposed water system OT within Canada, especially in connection to major geopolitical events.

Outlook: What this means for the Canadian water sector

In the Cyber Centre’s National Cyber Threat Assessment 2025-2026, we assess that the cyber threat to Canada’s critical infrastructure is almost certainly increasing. We judge that the primary threats to CI come from cybercrime, state-sponsored adversaries and, increasingly, from non-state actors. Changes in the geopolitical environment have elevated the profile and importance of critical infrastructure as a target for cyber activity. This has combined with the increasing interconnectivity of IT and OT in the water sector to increase the cyber threat to the water supply.

If Canada’s water infrastructure was to become a priority for state-sponsored actors, for example in the case of imminent or active armed conflict, we assess that any water system organizations with OT devices exposed to the Internet are almost certainly a target for disruptive cyber threat activity. Water systems may also be affected by cyber activity against other sectors due to the interconnected nature of infrastructure and supply chain complexity. For example, systems including water treatment plants, pumping stations, and distribution networks without backup power capacity may be vulnerable to disruptions in the energy sector, which may lead to interruptions in the treatment, storage and distribution of safe water to clients.

Defending Canada’s water sector against cyber threats and related influence operations requires addressing both the technical and social elements of cyber threat activity. These include threats that originate in the digital supply chain, and the technology and skills shortage in the sector. There are almost certainly water system operators in Canada with exposed devices. The Cyber Centre encourages all critical infrastructure asset owners, including those in the water sector, to take appropriate mitigation measures to protect their systems against cyber threats.

Mitigation

The Cyber Centre is dedicated to advancing cyber security and increasing the confidence of Canadians in the systems they rely on daily. This includes offering support to CI and other systems of importance to Canada. We approach security through collaboration, combining expertise from government, industry and academia. Working together, we can increase Canada’s resilience against cyber threats. Cyber security investments will allow OT asset operators to benefit from new technologies, while avoiding undue risks to the safe and reliable provision of critical services to Canadians.

The following mitigation measures can help water systems operators prevent cyber threat actors from exploiting vulnerable systems, attacking devices and networks and stealing sensitive data. Each of the mitigations below are linked to the Cyber Centre’s Cyber Security Readiness Goals (CRGs). The CRGs are a set of baseline cyber security practices an organization can take to bolster their cyber security posture. Further details of each goal can be found in the Cross-Sector Cyber Security Readiness Goals Toolkit. The mitigations below are highlighted to help prevent and reduce cyber attacks against the water sector.

Protect all management interfaces

Phishing-resistant MFA (CRG 2.7)

Implement phishing-resistant multi-factor authentication (MFA) for access to assets, including all remote access to the OT network.Footnote 33

IT accounts:

All IT accounts should leverage MFA to access organizational resources. Prioritize accounts with the highest risk, such as privileged administrative accounts for key IT systems.

OT environments:

Enable MFA on all accounts and systems that can be accessed remotely, including:

- vendor or maintenance accounts

- remotely accessible user and engineering workstations

- remotely accessible human-machine interfaces (HMIs)

Secure administrator workstation (CRG 2.21)

Set up and enforce the use of a secure administrator workstation (SAW) for administrators to perform administrative tasks.

A hardened SAW:

- is not connected to the corporate IT network

- is unable to install other software

- does not have access to the public Internet or email services

In cases where there is an operational requirement to use a SAW remotely, secure the SAW network traffic by using a layer 3 virtual private network (VPN). The protocols most widely used for VPNs are:

- Internet Protocol Security (IPSec)

- Transport Layer Security (TLS)

An IPSec VPN is an open standard, meaning that anyone can build a client or server that works with other IPSec implementations. IPSec VPN encrypts and authenticates all data in both directions and can enforce no split tunneling from the SAW.

TLS VPNs often use custom, non-standard features to tunnel traffic via TLS. Using custom or non-standard features creates additional risk exposure, even when the TLS parameters used by products are secure.

Keep in mind that the public Internet may not be reliable in a global crisis or major disaster. As such, local administration must always be maintained as a capability in CI.

Secure the supply chain

Vendor/supplier cyber security requirements (CRG 0.2)

Include cyber security vendor/supplier requirements and questions in organizations’ procurement documents. Ensure those responses are evaluated such that, given two offerings of roughly similar cost and function, the more secure offering and/or supplier is preferred.

Prevent credential theft

Changing default passwords (CRG 2.0)

Change default passwords and ensure your organization enforces a policy and/or process that requires changing default manufacturer passwords for all hardware, software and firmware.

If feasible, change default passwords on Programmable Logic Controllers (PLCs) and Human Machine Interfaces (HMIs). Ensure the Unitronics PLC default password “1111” is not in use.Footnote 33

Email security (CRG 2.11)

Secure all corporate email infrastructure to reduce the risk of common email-based threats such as spoofing, phishing and interception. On all corporate email infrastructure:

- enable STARTTLS

- enable Sender Policy Framework and DomainKeys Identified Mail

- enable Domain-based Message Authentication, Reporting and Conformance (DMARC) and set to “reject”

- encrypt emails to an appropriate and approved level in accordance with the sensitivity of the email contents

Basic and OT cyber security training (CRG 2.8)

Provide training that covers basic security and privacy concepts and foster an internal culture of security and cyber awareness. Ensure that personnel who maintain or secure OT as part of their regular duties receive OT-specific cyber security training at least annually. Training topics should include, at a minimum:

- phishing

- business email compromise

- basic operational security

- password security

- privacy breaches

Disable macros by default (CRG 2.12)

Establish a system-enforced policy that disables Microsoft Office macros or similar embedded code by default on all devices. If macros must be enabled in specific circumstances, set a policy that requires users to obtain authorization before macros are enabled for specific assets.

Protect internet-accessible vulnerable assets and services

No exploitable services on the internet (CRG 2.20)

Do not expose exploitable services, like remote desktop protocol, to the Internet. Where services must be exposed, implement appropriate compensating controls to prevent common forms of exploitation.

Limit OT connections to public Internet (CRG 2.18)

Ensure no OT assets, including PLCs, are connected to the public Internet.

In exceptional operational circumstances where remote access to the PLC is required, ensure that:

- exceptions are justified and documented; and

- additional protections are in place to prevent and detect exploitation attempts such as:

- logging

- MFA

- SAW

- mandatory access via proxy or another intermediary

Network segmentation (CRG 2.5)

Establish segmentation across network architecture to create boundaries and limit communication between IT and OT networks.

Ensure that all connections to the OT network are denied by default unless explicitly allowed (for example, by IP address and port) for specific system functionality.

Necessary communications paths between the IT and OT networks must pass through an intermediary (such as a properly configured firewall, bastion host, jump box or a demilitarized zone) which is closely monitored, captures network logs and only allows connections from approved assets.

Mitigating known vulnerabilities (CRG 1.1)

Apply patches for internet-facing systems within a risk-informed timespan, prioritizing the most critical assets first.

Identify security vulnerabilities in your systems by conducting penetration tests and using automated vulnerability scanning tools, activities which are part of a comprehensive vulnerability management strategy.

For OT assets where patching is not possible or may substantially compromise availability or safety, apply and record compensating controls (such as segmentation or monitoring). Sufficient controls either make the asset inaccessible from the public Internet or reduce the ability of threat actors to exploit the vulnerabilities in these assets.

Improve cyber security incident response capability

Incident response plans (CRG 1.3)

Develop, maintain, update and regularly drill IT and OT cyber security incident response plans for both common and organization-specific threat scenarios and TTPs. Regularly test manual controls so that critical functions can keep running if OT networks need to be taken offline.

Asset inventory and network topology (CRG 1.0)

Maintain a regularly updated inventory of all assets within the organization’s IT and OT networks. Include accurate documentation of network topology and identified data assets. Immediately log any new asset that is integrated into the organization’s infrastructure.

System backups and redundancy (CRG 2.14)

Implement regular system backup procedures on both IT and OT systems. Ensure backups are stored separately from the source systems and test on a recurring basis.

Ensure stored information for OT assets includes:

- configurations

- roles

- PLC logic

- engineering drawings

- tools

Implement adequate redundancies such as network components and data storage.

Ensure that the redundant secondary system is not collocated with the primary system and can be activated without loss of information or disruption to operations.

Additional resources

Assess:

- National Cyber Threat Assessment 2025-2026

- National Cyber Threat Assessments

- Baseline cyber threat assessment: Cybercrime

- The cyber threat from supply chains

- Cyber threat bulletin: Cyber threat to operational technology

Prepare:

- Cyber Security Readiness Goals: Securing Our Most Critical Systems

- Cross-Sector Cyber Security Readiness Goals Toolkit

- Security considerations for critical infrastructure (ITSAP.10.100)

Protect:

- Cyber threat bulletin: Cyber Centre reminds Canadian critical infrastructure operators to raise awareness and take mitigations against known Russian-backed cyber threat activity

- Joint guidance for executives and leaders of critical infrastructure organizations on protecting infrastructure and essential functions against PRC cyber activity

- Joint advisory on PRC state-sponsored actors compromising and maintaining persistent access to U.S. critical infrastructure and joint guidance on identifying and mitigating living off the land

- Protect your operational technology (ITSAP.00.051)

- Cyber supply chain: An approach to assessing risk (ITSAP.10.070)

- Protecting your organization from software supply chain threats (ITSM.10.071)