Alternate format: National Cyber Threat Assessment 2025-2026 (PDF, 4.22 MB)

About the Cyber Centre

The Canadian Centre for Cyber Security (Cyber Centre) is Canada’s technical authority on cyber security. Part of the Communications Security Establishment Canada (CSE), we are the single unified source of expert advice, guidance, services, and support on cyber security for Canadians and Canadian organizations.

The Cyber Centre works in close collaboration with Government of Canada departments, critical infrastructure, Canadian businesses, and international partners to prepare for, respond to, mitigate, and recover from cyber events. The Cyber Centre is outward-facing, welcoming partnerships that help build a stronger, more resilient cyberspace in Canada. In line with the National Cyber Security Strategy, the Cyber Centre represents a more cooperative approach to cyber security in our country.

As trusted experts in cyber security, we help keep Canada and Canadians safe by:

- being a clear, trusted source of relevant cyber security information for Canadians, Canadian businesses, and critical infrastructure owners and operators

- providing tailored cyber security advice and guidance to protect the country’s most important cyber systems

- working side by side with provincial, territorial, municipal, and Indigenous governments, and private sector partners to solve Canada’s most complex cyber challenges

- developing and sharing our specialized cyber defence technology and knowledge

- defending cyber systems, including Government of Canada networks, by developing and deploying sophisticated cyber defence tools and technology

- leading the Government of Canada’s operational response during cyber events by using our expertise and access to provide information immediately useful for managing incidents

Through our work and partnerships, we help raise Canada’s cyber security bar so Canadians can live and work online safely and with confidence.

Table of contents

Minister's foreword

Cyber threats to Canada are becoming more complex and sophisticated, threatening our national security and economic prosperity. As a nation with a significant global presence, Canada is a valuable target for cybercriminals looking to make a profit and state adversaries aiming to disrupt the systems we rely on.

In the last two years, we have witnessed a sharp increase in both the number and severity of cyber incidents, many of which target our essential services. Actors outside our borders have also attempted to influence public opinion and intimidate our population, including in the Canadian diaspora, through coordinated cyber campaigns.

The Canadian Centre for Cyber Security’s National Cyber Threat Assessment 2025-2026 is an instrumental tool in our comprehension of cyber threats to Canada. The threat assessment draws on public reporting and classified intelligence to paint an overall picture of the current threat landscape, while also forecasting future trends. By offering reliable and timely information, the report empowers Canadian organizations and individuals to prepare for and defend against current and emerging threats.

Deepening our understanding of cyber threats enables us to enhance our readiness and, as threats evolve, the Cyber Centre will continue to look for new ways to combat them. Its team is at the forefront of enhancing our cyber security to protect Canadians. Our government is supporting their invaluable work and Budget 2024 allocates $917.4 million to enhance intelligence and cyber operations programs to respond to evolving national security threats.

The insights provided in this threat assessment are critical as we work to strengthen Canada’s security in an increasingly digital world.

The Honourable Bill Blair

Minister of National Defence

Message from the Head of the Cyber Centre

It’s hard to believe it’s already been two years since our last report. At first glance, it seems that the cyber threat environment hasn’t changed much. Cybercrime remains a persistent threat, ransomware attacks continue to target our critical infrastructure, and state-sponsored cyber threat activity is still affecting Canadians.

What has changed, however, is that state adversaries are getting bolder and more aggressive. Cybercriminals driven by profit are increasingly benefiting from new illicit business models to access malicious tools and are using artificial intelligence to enhance their capabilities. Non-state actors are seizing on major global conflicts and political controversies to carry out disruptive activities.

These new developments and other trends are outlined in detail in this edition of the National Cyber Threat Assessment. This year’s report goes further than previous editions, offering more tangible examples of cyber threat activity in Canada and around the world, as well as providing some of our own statistics on cyber incidents.

While our assessments describe trends that should concern anyone who reads about them, you can rest assured that the Cyber Centre remains focused on tackling these threats. Working in close collaboration with the private sector, industry, government and critical infrastructure, we’re helping to protect the systems that are vital to our daily lives.

Whether you’re a first-time reader or an avid consumer, an individual Canadian or a member of a small, medium or large organization, I’m confident that you will find the information in this report insightful. I hope that it also encourages you to reflect on what you can do to contribute to our collective resilience. After all, we all have a role to play in building a safer, more secure Canada.

Sincerely,

Rajiv Gupta

Head, Canadian Centre for Cyber Security

Executive summary

Canada is confronting an expanding and complex cyber threat landscape with a growing cast of malicious and unpredictable state and non-state cyber threat actors, from cybercriminals to hacktivists, that are targeting our critical infrastructure and endangering our national security. These cyber threat actors are evolving their tradecraft, adopting new technologies, and collaborating in an attempt to improve and amplify their malicious activities.

Canada’s state adversaries are becoming more aggressive in cyberspace. State-sponsored cyber operations against Canada and our allies almost certainly extend beyond espionage. State-sponsored cyber threat actors are almost certainly attempting to cause disruptive effects, such as denying service, deleting or leaking data, and manipulating industrial control systems, to support military objectives and/or information campaigns. We assess that our adversaries very likely consider civilian critical infrastructure to be a legitimate target for cyber sabotage in the event of a military conflict.

At the same time, cybercrime remains a persistent, widespread, and disruptive threat to individuals, organizations, and all levels of government across Canada that is sustained by a thriving and resilient global cybercrime ecosystem. We assess that the financial motivations underpinning cybercrime will almost certainly drive the cybercrime ecosystem to continuously evolve and diversify as cybercriminals attempt to evade authorities.

Key judgements

- Canada’s state adversaries are using cyber operations to disrupt and divide. State-sponsored cyber threat actors are almost certainly combining disruptive computer network attacks with online information campaigns to intimidate and shape public opinion. State-sponsored cyber threat actors are very likely targeting critical infrastructure networks in Canada and allied countries to pre-position for possible future disruptive or destructive cyber operations.

- The People’s Republic of China’s (PRC) expansive and aggressive cyber program presents the most sophisticated and active state cyber threat to Canada today. The PRC conducts cyber operations against Canadian interests to serve high-level political and commercial objectives, including espionage, intellectual property (IP) theft, malign influence, and transnational repression. Among our adversaries, the PRC cyber program’s scale, tradecraft, and ambitions in cyberspace are second to none.

- Russia’s cyber program furthers Moscow’s ambitions to confront and destabilize Canada and our allies. Canada is very likely a valuable espionage target for Russian state-sponsored cyber threat actors, including through supply chain compromises, given Canada’s membership in the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, support for Ukraine against Russian aggression, and presence in the Arctic. Pro-Russia non-state actors, some of which we assess likely have links to the Russian government, are targeting Canada in an attempt to influence our foreign policy.

- Iran uses its cyber program to coerce, harass, and repress its opponents, while managing escalation risks. Iran’s increasing willingness to conduct disruptive cyber attacks beyond the Middle East and its persistent efforts to track and monitor regime opponents through cyberspace present a growing cyber security challenge for Canada and our allies.

- The Cybercrime-as-a-Service (CaaS) business model is almost certainly contributing to the continued resilience of cybercrime in Canada and around the world. The CaaS ecosystem is underpinned by flourishing online marketplaces where specialized cyber threat actors sell stolen and leaked data and ready-to-use malicious tools to other cybercriminals. This has almost certainly enabled a growing number of actors with a range of capabilities and expertise to carry out cybercrime attacks and evade law enforcement detection.

- Ransomware is the top cybercrime threat facing Canada’s critical infrastructure. Ransomware directly disrupts critical infrastructure entities’ ability to deliver critical services, which can put the physical and emotional wellbeing of victims in jeopardy. In the next two years, ransomware actors will almost certainly escalate their extortion tactics and refine their capabilities to increase pressure on victims to pay ransoms and evade law enforcement detection.

About this threat assessment

The National Cyber Threat Assessment 2025-2026 (NCTA 2025-2026) highlights the cyber threats facing individuals and organizations in Canada. It provides an update to the National Cyber Threat Assessment 2018 (NCTA 2018), the National Cyber Threat Assessment 2020 (NCTA 2020), and the National Cyber Threat Assessment 2023-2024 (NCTA 2023-2024), with analysis of the interim years and forecasts until 2026. We recommend reading the NCTA 2025-2026 along with the Introduction to the Cyber Threat Environment and the advice and guidance that we have released as companions to this assessment.

We prepared this assessment to help Canadians shape and sustain our nation’s cyber resilience. It is only when the government, the private sector, and the public work together that we can build resilience to cyber threats in Canada.

Sources

The key judgements in this assessment rely on reporting from multiple sources, both classified and unclassified. The judgements are based on CSE’s knowledge and expertise in cyber security. Defending the Government of Canada’s information systems provides CSE with a unique perspective to observe trends in the cyber threat environment, which also informs our assessment. CSE’s foreign intelligence mandate provides us with valuable insights into adversary behaviour in cyberspace. While we must always protect classified sources and methods, we provide the reader with as much justification as possible for our judgements.

Assessment process

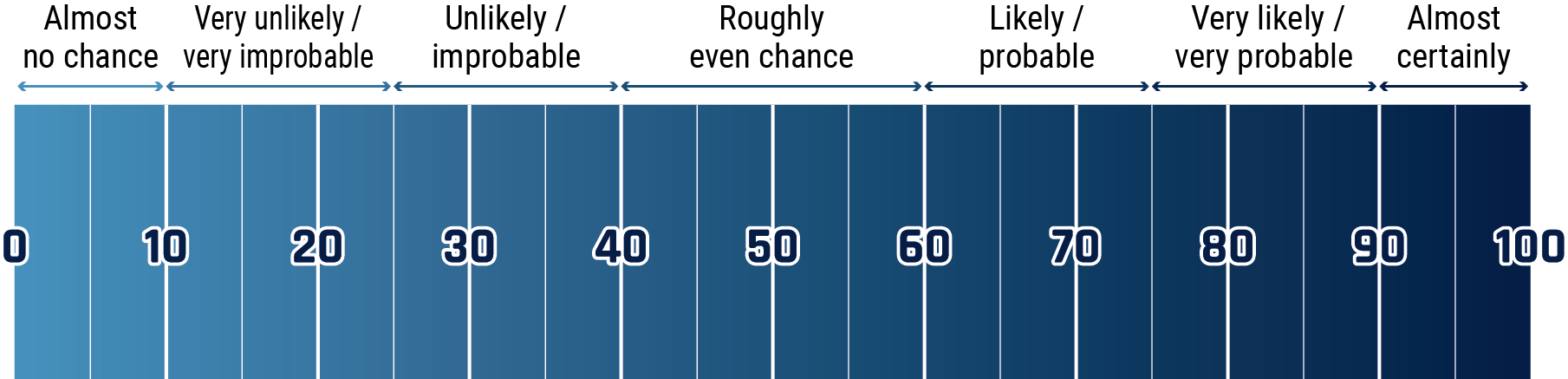

Our cyber threat assessments are based on an assessment methodology that includes evaluating the quality of available information, exploring alternative explanations, mitigating biases, and using probabilistic language. We use the terms “we assess” or “we judge” to convey an analytic assessment. We use qualifiers such as “possibly,” “likely,” and “very likely” to convey probability.

This threat assessment is based on information available as of September 20, 2024.

Limitations

This assessment does not provide an exhaustive list of all cyber threat activity in Canada or mitigation advice. The purpose of this threat assessment is to describe and evaluate the threats facing Canada. We focus on understanding the current cyber threat environment and how threat activity can affect Canadians and Canadian organizations. Cyber security guidance can be found on the Cyber Centre website and on the Get Cyber Safe website.

The chart below matches estimative language with appropriate percentages. these percentages are not derived via statistical analysis, but are based on logic, available information, prior judgements, and methods that increase the accuracy of estimates.

Long description - Estimative language chart

- 1 to 9% Almost no chance

- 10 to 24% Very unlikely/very improbable

- 25 to 39% Unlikely/improbable

- 40 to 59% Roughly even chance

- 60 to 74% Likely/probably

- 75 to 89% Very likely/very probable

- 90 to 99% Almost certainly

Introduction

Canada has entered a new era of cyber vulnerability where cyber threats are ever-present, and Canadians will increasingly feel the impact of cyber incidents that have cascading and disruptive effects on their daily lives.

Advancements in communications and computing technologies have ushered in a world of ubiquitous connectivity for Canadians. In this environment, online platforms and digital technologies continue to shape and mediate Canadians’ interactions with the physical world—the way we work, shop, travel, socialize, get informed, and access critical services.Footnote 1 These systems record and process vast amounts of data about us, often over poorly secured or untrustworthy digital networks.Footnote 2 These systems are also interconnected and fragile: cyber incidents, from cyber attacks to flawed software updates, can knock airlines, hospitals, banks, and retailers around the world offline.Footnote 3

CSE and its partners in Canada and across the Five Eyes are attuned to the cyber threats to Canada from state and non-state cyber threat actors and are tracking them as they evolve. NCTA 2025-2026 provides the Canadian public with CSE’s current insights on the state and non-state cyber threat actors conducting malicious cyber threat activity against Canada and how we assess the cyber threat landscape will evolve in the next two years. This assessment is divided into three sections that are designed to stand independently and together.

- Section 1—Cyber threat from state adversaries: introduces the state cyber threat ecosystem and discusses the cyber threats to Canada from

- the People’s Republic of China (PRC)

- the Russian Federation (Russia)

- the Islamic Republic of Iran (Iran)

- the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK)

- the Republic of India (India)

- Section 2—Cybercrime threats: discusses the interconnectivity of the Cybercrime-as-a-Service (CaaS) ecosystem and the cybercrime threats facing Canada, specifically from fraud, scams, and ransomware. This section also highlights the ransomware threat to Canada’s critical infrastructure.

- Section 3—Trends shaping Canada’s cyber threat landscape: identifies five trends that will shape Canada’s cyber threat landscape and drive cyber threat activity impacting Canadians up to 2026.

Readers interested in more detailed information on the evolving cyber threat landscape, including definitions of important terms and concepts referenced in this NCTA, are invited to consult the following:

Cyber threat from state adversaries

Canada is confronting an expanding and more complex state cyber ecosystem

Strategic adversaries

The cyber programs of the PRC , Russia, and Iran remain the greatest strategic cyber threats to Canada. These countries are united in their desire to challenge United States (U.S.) dominance in multiple domains, including cyberspace, and promote an authoritarian vision for Internet governance and domestic surveillance.Footnote 4 The PRC’s cyber program surpasses other hostile states in both the scope and resources dedicated to cyber threat activity against Canada.

Emerging cyber programs

At the same time, countries that aspire to become new centres of power within the global system, such as India, are building cyber programs that present varying levels of threat to Canada.Footnote 5 While emerging states focus their cyber efforts on domestic threats and regional rivals, they also use their cyber capabilities to track and surveil activists and dissidents living abroad.

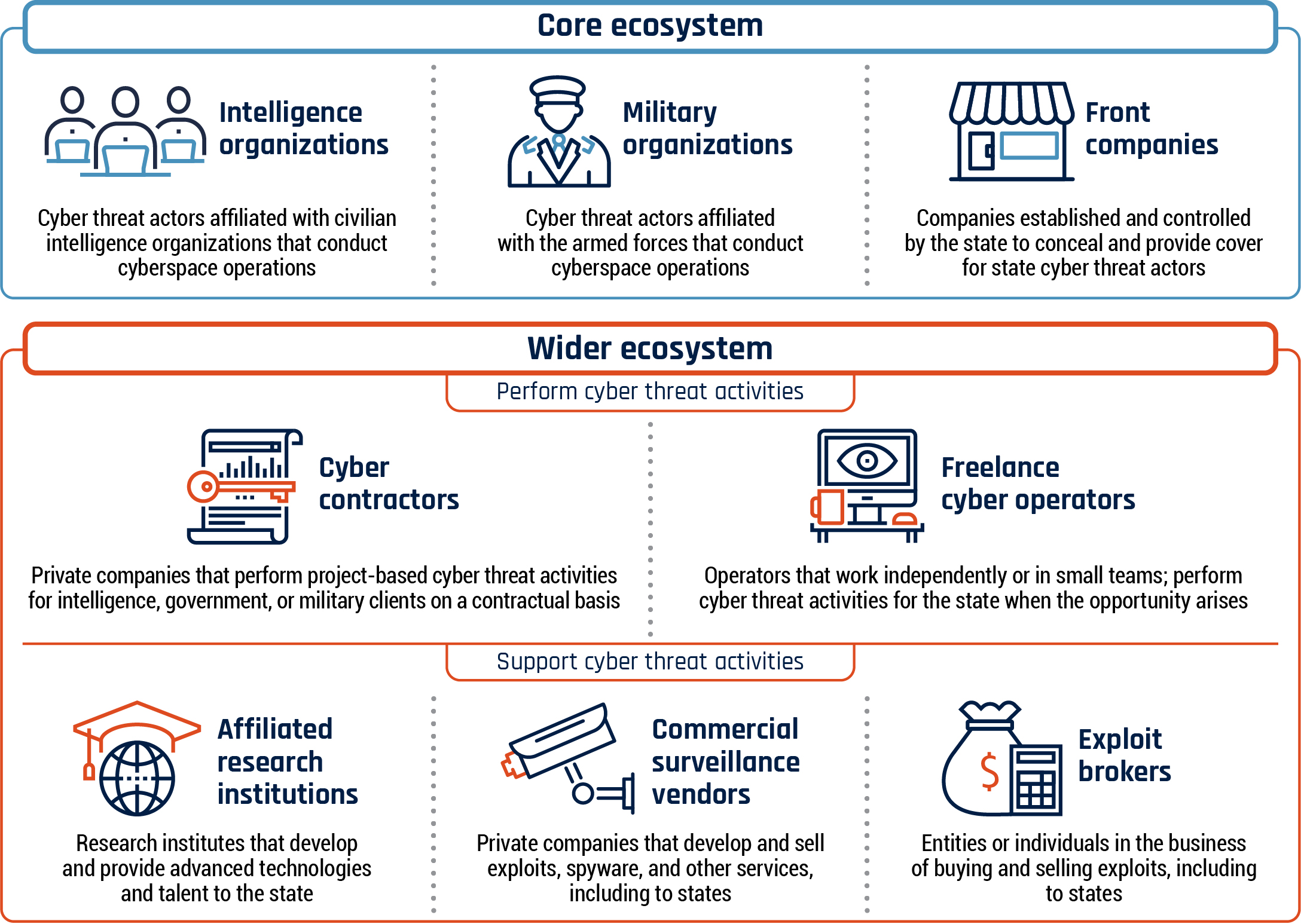

Wider cyber ecosystem

Both advanced and emerging states are leveraging a complex ecosystem of commercial surveillance vendors, contractors, and affiliated research institutions to support or perform cyber threat activities (Figure 1).Footnote 6 States use these entities to mask their cyber operations or to acquire exploits, digital infrastructure, and data. Emerging states are very likely using the wider ecosystem to try and move up the ladder of sophistication and acquire capabilities that may be beyond their capacity to develop internally.

Long description - Figure 1: State cyber program ecosystem

A graphic that describes the state cyber program ecosystem. The state cyber program ecosystem includes a core ecosystem and a wider ecosystem that are made up of various entities. Each entity in the ecosystem has an image with a brief description.

Core ecosystem

- Intelligence Organizations: Cyber threat actors affiliated with civilian intelligence organizations that conduct cyberspace operations

- Military Organizations: Cyber threat actors affiliated with the armed forces that conduct cyberspace operations

- Front Companies: Companies established and controlled by the state to conceal and provide cover for state cyber threat actors

Wider ecosystem

- Entities that perform cyber threat activities:

- Cyber contractors: Private companies that perform project-based cyber threat activities for intelligence, government, or military clients on a contractual basis

- Freelance cyber operators: Operators that work independently or in small teams; perform cyber threat activities for the state when the opportunity arises

- Entities that support cyber threat activities, include:

- Affiliated research institutions: Research institutes that develop and provide advanced technologies and talent to the state

- Commercial surveillance vendors: Private companies that develop and sell exploits, spyware, and other services, including to states

- Exploit brokers: Companies or individuals that are in the business of buying and selling exploits, including to states

People’s Republic of China

The PRC presents the most sophisticated and active cyber threat to Canada

The PRC's expansive and aggressive cyber program has global cyber surveillance, espionage, and attack capabilities and is the most comprehensive cyber security threat facing Canada today. Canada, along with our Five Eyes partners, is an ongoing target for the PRC's cyber program. The PRC conducts cyber operations against Canadian interests to serve high-level political and commercial objectives, including espionage, intellectual property (IP) theft, malign influence, and transnational repression. Among our adversaries, the PRC cyber program’s scale, tradecraft, and ambitions in cyberspace are second to none.

The PRC targets all levels of government and public officials for valuable intelligence

Over the past four years, at least 20 networks associated with Government of Canada agencies and departments have been compromised by PRC cyber threat actors.

PRC state-sponsored cyber threat actors persistently conduct cyber espionage against federal, provincial, territorial, municipal, and Indigenous government networks in Canada. PRC cyber threat actors have compromised and maintained access to multiple government networks over the past five years, collecting communications and other valuable information.Footnote 8 While all known federal government compromises have been resolved, it is very likely that the actors responsible for these intrusions dedicated significant time and resources to learn about the target networks.

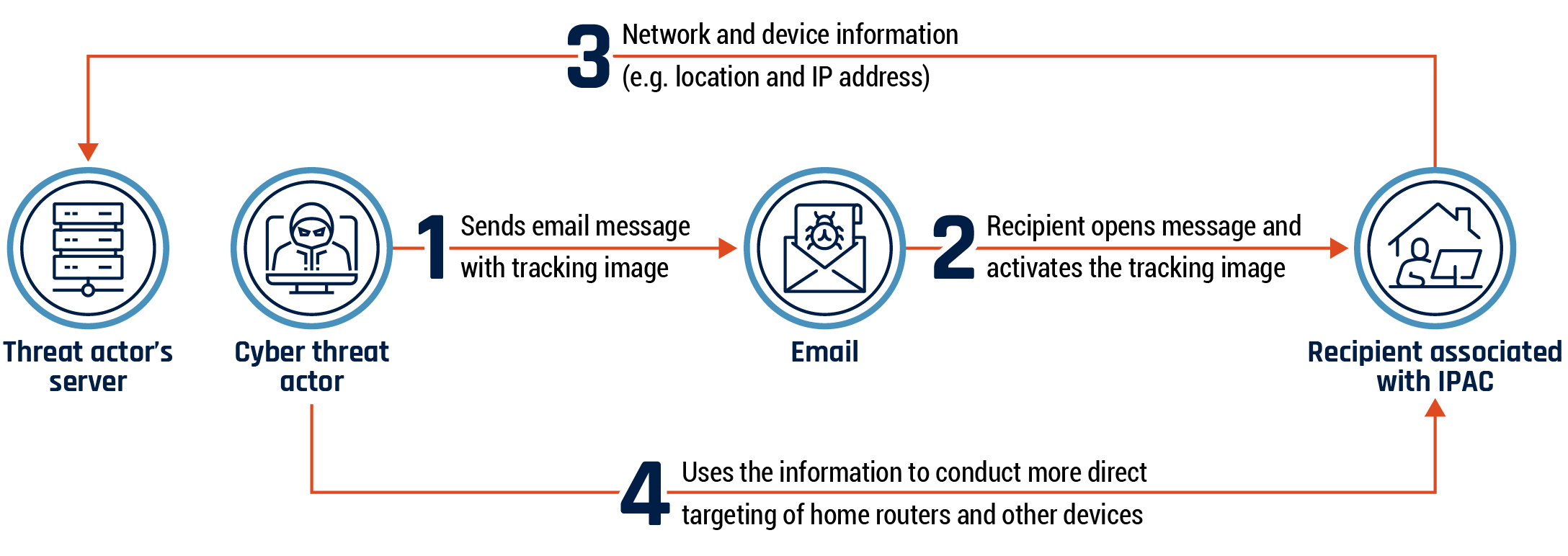

PRC state-sponsored cyber threat actors also target Canadian government officials, particularly individuals that the PRC perceives as being critical of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). According to a U.S. Department of Justice indictment, in 2021, PRC state-sponsored cyber threat actors targeted members of the Inter-Parliamentary Alliance on China (IPAC), a group of global lawmakers whose stated purpose is to counter the threats posed by the CCP to the international order and democratic principles. The threat actors sent email messages with tracking images to recipients to conduct network reconnaissance. (see Figure 2).Footnote 9 A number of Canadian politicians who are members of IPAC have come forward to confirm that they were targeted in this operation.Footnote 10

Long description - Figure 2: PRC email operation against members of Inter-Parliamentary Alliance on China

A graphic of the steps in a PRC email operation against members of the Inter-Parliamentary Alliance on China. There are four entities in the operation:

- Threat actor’s server

- Cyber threat actor

- Email with tracking image

- Recipient associated with IPAC

Each entity in the operation is represented by a circle with an image. Each step in the operation is represented by a bolded number with a description of the step.

The steps to the operation are as follow:

- Cyber threat actor sends email message with tracking image to recipient

- Recipient opens message and activates the tracking image

- Recipient’s network and device information, including location and IP address, is sent to a server controlled by the cyber threat actor

- Cyber threat actor uses the information to conduct more direct targeting of recipient’s home routers and other devices

The PRC targets Canadian government networks and public officials to acquire information that will advance its strategic, economic, and diplomatic interests, and give the PRC government an advantage in China-Canada bilateral relations and commercial matters. For example, provincial and territorial governments are likely a valuable target given that they have decision-making power over regional trade and commerce, including resource extraction (e.g., energy and critical minerals).Footnote 8 In addition to fulfilling PRC intelligence collection priorities, the information collected is also likely used to support the PRC’s malign influence and interference activities against Canada’s democratic processes and institutions.

PRC cyber threat activity against Canada appears to intensify following events that increase bilateral tensions between Canada and the PRC . In this context, PRC cyber threat activity is likely designed to gather timely intelligence on official reactions and to monitor unfolding developments.

PRC cyber-enabled transnational repression targets individuals in Canada

PRC cyber threat actors very likely support China’s actions abroad designed to silence activists, journalists, diaspora communities, and other groups that the PRC views as security threats. These groups, collectively referred to by PRC officials as the “Five Poisons,” include:

- Falun Gong practitioners

- Uyghurs

- Tibetans

- supporters of Taiwanese independence

- pro-democracy activists

PRC actors very likely facilitate transnational repression by monitoring and harassing these groups online and tracking them using cyber surveillance.Footnote 11 For example, the PRC has been publicly linked to cyber espionage operations against the Uyghur minority group, including members living in Canada, using spear phishing emails and spyware.Footnote 12

The PRC government very likely leverages Chinese-owned technology platforms, some of which likely cooperate with the PRC's intelligence and security services, to facilitate transnational repression.Footnote 13

The PRC targets Canada’s private sector and innovation ecosystem for competitive advantage

Canada’s innovation ecosystem has been a long-standing priority of PRC intelligence collection. The PRC cyber program almost certainly continues to support the PRC's espionage activities against Canada’s private sector, academia, supply chains, and government-affiliated research and development (R&D). PRC cyber threat actors have very likely stolen commercially sensitive data from Canadian firms and institutions.

The PRC uses cyber contractors and freelancers to support espionage

The PRC uses a competitive marketplace of contract and freelance cyber actors to support the PRC's intelligence collection requirements. For example, I-Soon is a PRC -based private contractor that provides “hacker-for-hire” services. According to leaked documents, the company worked on projects on a contractual basis for various PRC government and military entities and state-owned enterprises. I-Soon reportedly sold exfiltrated data from targets to its clients.Footnote 14

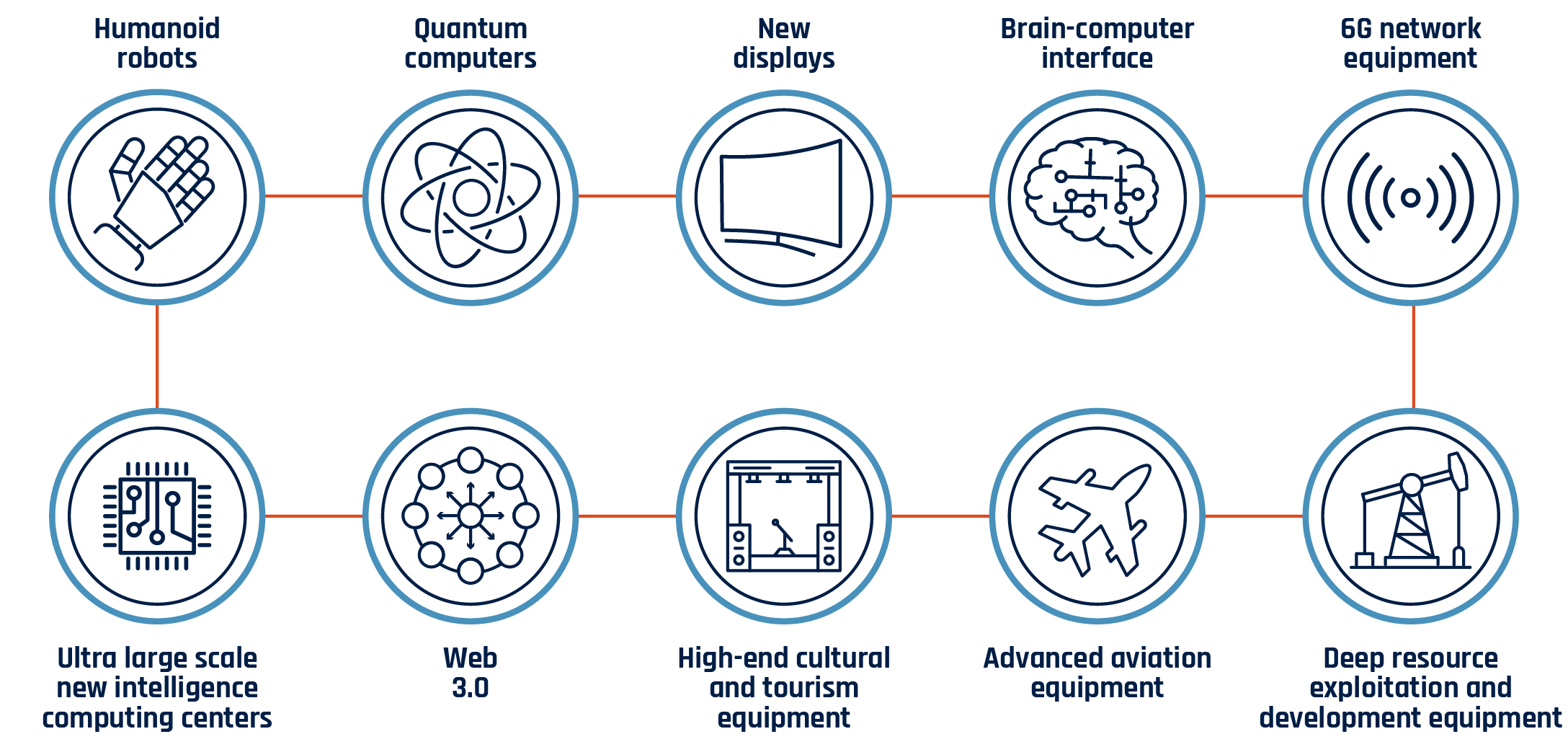

PRC cyber threat actors targeting Canada likely prioritize collecting confidential and proprietary information that supports the PRC's economic and military interests and that can help accelerate the PRC’s development of advanced and strategic technologies (Figure 3). The PRC will likely intensify its espionage activities against Canada’s innovation sector as economic tensions between the PRC and Canada (and our allies) rise.Footnote 9

Long description - Figure 3: Future industries “iconic products” identified as priorities for PRC industrial policy (2024)

A graphic that identifies ten future industries “iconic products” identified as priorities for PRC industrial policy. Each iconic product is represented by a separate circle with an image. The ten iconic products are as follows:

- Humanoid robots

- Quantum computers

- New displays

- Brain-computer interface

- 6G network equipment

- Ultra large scale new intelligence computing centers

- Web 3.0

- High-end cultural and tourism equipment

- Advanced aviation equipment

- Deep resource exploitation and development equipment

PRC pre-positioning within United States critical infrastructure increases risk to Canada

In a strategic shift, the PRC is very likely integrating offensive cyber operations into its military planning to gain an advantage during a potential conflict with the U.S. PRC state-sponsored cyber threat actors, tracked as Volt Typhoon, are almost certainly seeking to pre-position within U.S. critical infrastructure networks for disruptive or destructive cyber attacks in the event of a major crisis or conflict with the U.S. According to U.S. officials, the PRC's operation is designed to slow the U.S. military’s response and to sow societal panic.Footnote 16 Volt Typhoon is especially noteworthy because the PRC has not historically conducted disruptive or destructive cyber operations against critical infrastructure.Footnote 17

We assess that the direct threat to Canada’s critical infrastructure from PRC state-sponsored cyber threat actors is likely lower than that to U.S. infrastructure. While the focus of future PRC cyber warfare operations will likely be concentrated on the U.S., disruptive or destructive cyber threat activity against integrated North American critical infrastructure, such as pipelines, power grids, and rail lines, would likely affect Canada as well due to cross-border interoperability and interdependence.Footnote 8

Russian Federation

Russia is leveraging its cyber program to confront the West

Russia’s unpredictable cyber program routinely challenges existing norms in cyberspace and furthers Moscow’s ambitions to confront and destabilize Canada and our allies.

Russia almost certainly views its cyber program as part of a multi-layered strategy to influence and shape the information environment. Russia combines conventional cyber espionage and computer network attacks with disinformation and influence operations to:Footnote 18

- promote Russia’s global status and reinforce pro-Russia narratives

- erode trust in democratic institutions

- generate popular support for Russia’s war efforts, both at home and abroad

- psychologically weaken or embarrass its opponents

Russia’s cyber threat activities are supported by a network of state and non-state cyber actors, including an ever-shifting group of Russia-nexus cybercriminals, hacktivists, and “hackers-for-hire” who are likely motivated by a mix of patriotism, profit, or opportunism. This hybrid strategy, which provides Russia with deniability, appears to have been emulated by other states, creating a more complex cyber threat environment for Canada and our allies.Footnote 19

Russian cyber threat actor conducts destructive cyber attack against Ukraine for psychological effects

In December 2023, a Russian cyber threat actor conducted a destructive wiper cyberattack against the Ukrainian telecom company Kyivstar, leaving millions of Ukrainians without Internet and mobile service for days. The cyber threat actor was reportedly in Kyivstar’s systems since at least May 2023 and may have been able to steal subscriber information and intercept SMS-messages. The actor claimed credit for the attack in a Telegram post addressed to Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelenskyy. According to Ukrainian officials, the aim of the destructive attack was to land a psychological blow against Ukraine.Footnote 20

Russia targets Canada for espionage

Canada is very likely a valuable espionage target for Russian state-sponsored cyber threat actors given Canada’s membership in the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, support for Ukraine, and presence in the Arctic. Russian cyber threat actors are very likely targeting Canadian government, military, private sector, and critical infrastructure networks as part of Russia’s foreign and military intelligence collection operations.Footnote 21

Public and private sector organizations in Canada are also vulnerable to global supply chain compromises by Russian cyber threat actors. For example, in 2020, Russian state-sponsored cyber threat actors compromised the supply chain by implanting malware into a SolarWinds software update.Footnote 22 Russian-state-sponsored cyber threat actors are almost certainly targeting cloud-based services with large numbers of customers in Canada.Footnote 23

Russian cyber threat actor compromises Microsoft corporate email system for espionage

In January 2024, Microsoft detected that a Russian state-sponsored cyber threat actor publicly tracked by Microsoft as Midnight Blizzard had breached Microsoft’s cloud-based enterprise email service. Midnight Blizzard accessed Microsoft’s own corporate email accounts, exfiltrating correspondences between Microsoft and government officials in Canada, the U.S., and the United Kingdom.Footnote 24 According to Microsoft, the Russian cyber threat actor was initially seeking information about itself.Footnote 25 The threat actor later used personal data and credentials in the emails to attempt to gain access to Microsoft customer systems.

Pro-Russia non-state cyber threat actors target Canada to influence our foreign policy

Following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, pro-Russia non-state (PRNS) cyber threat actors, some of which we assess likely have links to the Russian government and intelligence services, have almost certainly conducted disruptive cyber threat activity against Canada and leveraged social media to draw attention to these attacks (Figure 4).Footnote 26 We assess that the intent of these campaigns is very likely to influence and undermine Canada’s support for Ukraine. For example, a distributed denial of service (DDoS) attack campaign in April 2023 by PRNS actors against Government of Canada and Canadian private sector websites coincided with the Ukrainian Prime Minister’s visit to Canada.Footnote 27

February 2023

Pro-Russia non-state cyber groups participate in a cyber campaign attempting to sabotage critical infrastructure in countries providing assistance to Ukraine, including Canada.

April 2023

Pro-Russia non-state cyber group claims responsibility for DDoS campaign against Canadian websites, including the Prime Minister’s Office’s public-facing website.

September 2023

Pro-Russia non-state cyber group claims responsibility for a DDoS campaign against Canadian websites, including Quebec provincial government websites.

Although PRNS cyber threat activity against Canada has primarily consisted of DDoS attacks and website defacements, some PRNS actors have attempted to compromise operational technology (OT) systems within critical infrastructure in North America and Europe with the intent to disrupt those systems. This activity opportunistically targets internet-accessible devices and exploits basic vulnerabilities, such as insecure remote access software or the use of default passwords.Footnote 29 For example, in January 2024, a PRNS group claimed responsibility for the overflow of water storage tanks at water facilities in Texas. The group reportedly posted a video of the compromise and manipulation of control systems at each facility on a public forum.Footnote 30

We assess that PRNS actors will likely attempt to disrupt vulnerable Internet-connected OT systems within Canadian critical infrastructure when the opportunity arises. PRNS cyber threat activity against OT may cause systems to malfunction, leading to damage or destruction of those systems and possible harm to public safety.

Islamic Republic of Iran

Iran is expanding its disruptive cyber threat activity against the West

Iran has an aggressive cyber program that the regime uses to coerce, harass, and repress Iran’s opponents, while managing escalation risks. Iran’s increasing willingness to conduct disruptive cyber attacks beyond the Middle East, and its persistent efforts to track and monitor regime opponents through cyberspace present a growing cyber security challenge for Canada and our allies.

Iran has taken advantage of its back-and-forth cyber confrontation with Israel to improve its cyber espionage and offensive cyber capabilities and hone its information campaigns, which it is now almost certainly deploying against targets in the West.Footnote 31 While it is unlikely that Canada is, at present, a priority target of Iran’s cyber program, Iranian cyber threat actors likely have access to computer networks in Canada, including critical infrastructure.

Iran’s global coercive cyber operations present a risk to Canada

Iranian state-sponsored cyber threat actors have planned and conducted multi-stage disruptive cyber operations around the world to intimidate Iran’s opponents, signal the regime’s displeasure, and persuade a country to change its behaviour (Figure 5).Footnote 32

Iranian cyber threat actors have performed denial of service attacks, attempted to manipulate industrial control systems, and accessed government and private networks to encrypt, wipe, and leak data. Iran has developed a network of hacktivist personas and social media channels that exploit these disruptive events to spread the regime’s messages and influence the target society while keeping Tehran’s official involvement ambiguous and deniable.Footnote 33

We assess that escalation of tensions in Canada-Iran bilateral relations would very likely increase the risk that Canada would be a target of Iranian coercive cyber operations.

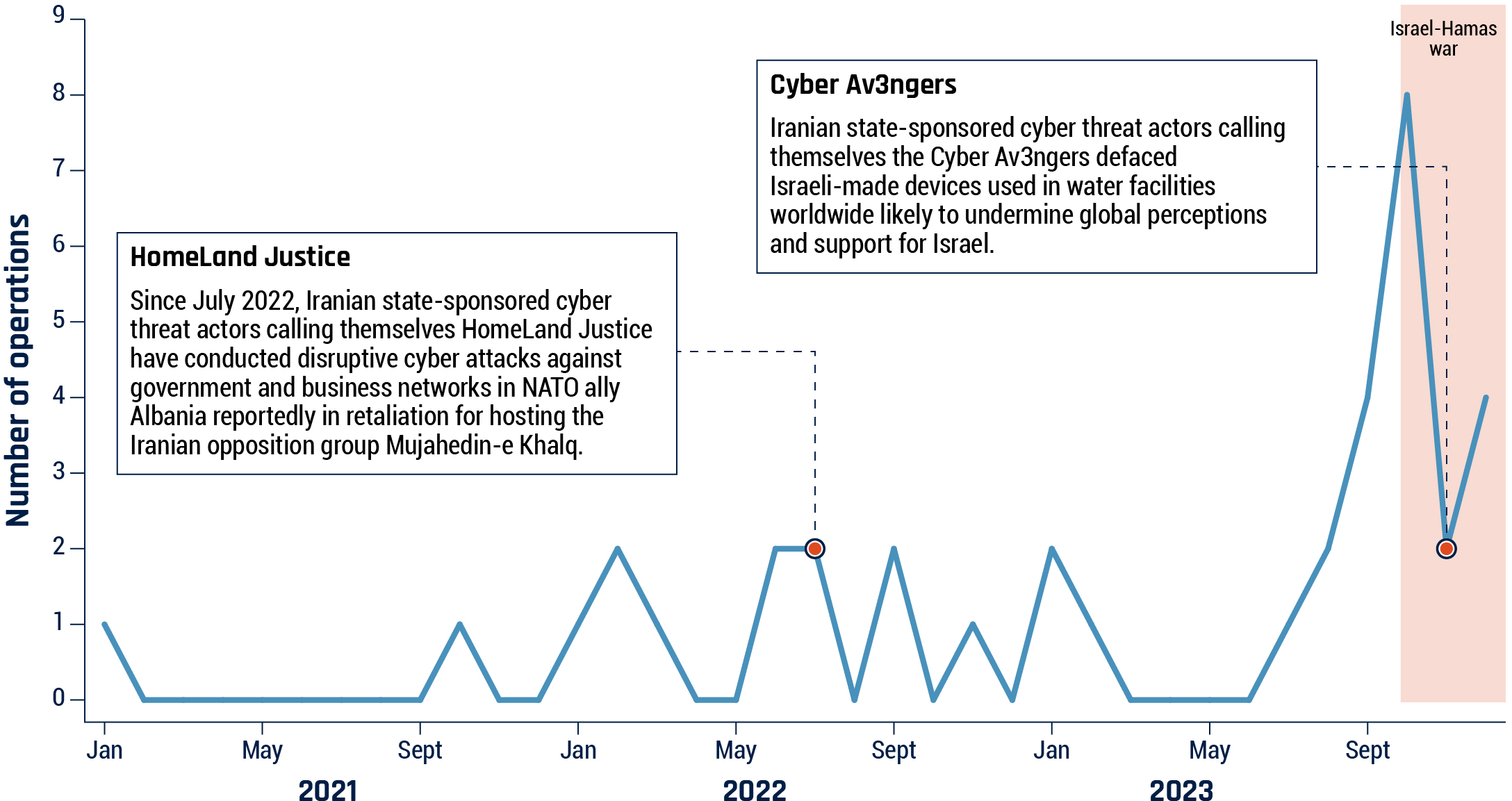

Long description - Figure 5: Coercive cyber operations publicly linked to Iran (2021-2023)

A line graph showing the number of coercive cyber operations publicly linked to Iran for each month from January 2021 to December 2023. The x axis represents the months from January 2021 and December 2023. The y axis represents the number of operations from 1 to 9.

| Year | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | June | July | Aug | Sept | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 2022 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 2023 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 2 | 4 |

Two examples of Iranian coercive cyber operations are highlighted with a red dot in the chart and described in detail in a textbox.

- Example 1 describes an operation by HomeLand Justice starting in July 2022: Since July 2022, Iranian state-sponsored cyber threat actors calling themselves HomeLand Justice have conducted disruptive cyber attacks against government and business networks in NATO ally Albania reportedly in retaliation for hosting the Iranian opposition group Mujahedin-e Khalq.

- Example 2 describes an operation by Cyber Av3ngers starting in October 2023: Iranian state-sponsored cyber threat actors calling themselves the Cyber Av3ngers defaced Israeli-made devices used in water facilities worldwide likely to undermine global perceptions and support for Israel.

Iran uses social engineering for transnational repression and espionage

Iranian state-sponsored cyber threat actors likely track and monitor individuals in Canada whom the Iranian regime considers a threat, such as political activists, journalists, human rights researchers, and members of the Iranian diaspora. Iranian cyber threat groups are particularly sophisticated in combining social engineering with spear phishing to support Iran’s transnational repression and surveillance activities (Figure 6).Footnote 35 For example, Iran has very likely used the downing of Flight 752 over Tehran as a thematic lure for its social engineering and spear phishing operations. These efforts are especially concerning given recent public reports linking Iran to kidnapping and assassination plots against regime opponents living in the West.Footnote 36

Figure 6: Elements of an Iranian social engineering campaign

Use of personas: Iranian cyber threat actors use fake personas (e.g., attractive females) or impersonate real individuals (e.g., journalists) to manipulate their targets.

Building trust: Personas build trust with targets by exploiting emotional vulnerabilities or offering false professional or media opportunities.

Malicious activity: Iranian cyber threat actors send a malicious link, document, or malicious apps to targets to harvest credentials or deliver malware.

Iran also uses its social engineering efforts to target public officials and gain access to government networks and private sector organizations globally, including in the aerospace, energy, defence, travel, and telecommunications sectors, in pursuit of its intelligence collection requirements.Footnote 37

The Democratic People’s Republic of Korea

The DPRK has a dual-purpose cyber program that prioritizes revenue generation alongside the pursuit of the regime’s strategic and intelligence requirements. DPRK state-sponsored cyber threat actors routinely engage in cybercrime activities, such as ransomware and cryptocurrency theft, to fund the regime’s political and military ambitions as well as the cyber program’s own operations.Footnote 38 These financially motivated attacks are very likely conducted under the overarching strategic direction and protection of the North Korean regime, which likely tolerates cybercrime activities that have harmful and disruptive effects.Footnote 39

While we assess that the DPRK's cyber program almost certainly does not pose a strategic cyber threat to Canada on par with countries like the PRC and Russia, the regime’s commitment to cybercriminal statecraft almost certainly presents a persistent and well-resourced cybercrime threat to individuals and organizations in Canada across a broad range of industries and sectors of the economy. The DPRK will almost certainly continue to adapt and pivot to new cybercriminal enterprises as digital technologies evolve.Footnote 40

Republic of India

India’s leadership almost certainly aspires to build a modernized cyber program with domestic cyber capabilities.Footnote 41 India very likely uses its cyber program to advance its national security imperatives, including espionage, counterterrorism, and the country’s efforts to promote its global status and counter narratives against India and the Indian government. We assess that India’s cyber program likely leverages commercial cyber vendors to enhance its operations.Footnote 42

We assess that Indian state-sponsored cyber threat actors likely conduct cyber threat activity against Government of Canada networks for the purpose of espionage. We judge that official bilateral relations between Canada and India will very likely drive Indian state-sponsored cyber threat activity against Canada.

Cybercrime threats

Interconnected online cybercrime ecosystem facilitates Cybercrime-as-a-Service

Financially motivated and opportunistic cybercrime continues to be the cyber threat activity that is most likely to affect Canadians and Canadian organizations. We judge that the continued resilience of cybercrime in Canada and around the world is almost certainly due, in part, to the rise of the Cybercrime-as-a-Service (CaaS) business model. With CaaS , specialized threat actors sell stolen and leaked data and ready-to-use malicious tools to other cybercriminals online, enabling their illicit activities.Footnote 46

CaaS services available online for cybercriminals to purchase

- Malware-as-a-Service: services to support the development and deployment of malware that can steal or encrypt victim data or gain remote control of victim systems

- Ransomware-as-a-Service (RaaS): a core group of developers will sell or lease their ransomware variant to other threat actors, called affiliates; the core developers will support affiliates’ deployment of their ransomware in exchange for upfront payment, subscription fees, a cut of profits, or all three

- Access-as-a-Service: specialized threat actors gain access to victim systems and sell access to compromised systems to clients

- Phishing-as-a-Service (PaaS): detailed instructions, email templates, and ready-to-use tools for executing phishing attacks

- DDoS-as-a-Service: rented out botnets and user-friendly interfaces for clients to conduct DDoS attacks

- Exploits-as-a-Service: specialized actors lease or rent exploit kits and support clients on how to use exploits against software vulnerabilities

Figure 7: How cybercriminals use online platforms

Marketplaces: Criminal online platforms that function similarly to legitimate online marketplaces like Etsy or eBay. Cybercriminals use marketplaces to buy or sell cybercrime tools and services.Footnote 43

Forums: Cybercriminals use forums to purchase illicit tools and services and connect with other cybercriminals.Footnote 44

Chat platforms: Cybercriminals use encrypted messaging platforms like Telegram to communicate in private channels tailored to various cybercrime topics.Footnote 45

We assess that CaaS has almost certainly increased the number of actors participating in cybercrime by lowering the barrier to entry and enabling actors who are less technically sophisticated to carry out cybercrime attacks. Even large cybercriminal groups leverage CaaS offerings such as malware, cyber attack infrastructure (e.g., hosting infrastructure) and money laundering services to increase their capacity for cybercrime activity.Footnote 47

Online platforms play an important role in enabling cybercrime

The cybercrime ecosystem is highly interconnected. Online platforms such as cybercrime marketplaces, forums and chat platforms facilitate the sale and resale of stolen data as well as interactions between CaaS providers and cybercriminals seeking their services. These online platforms also play a significant role by facilitating professional connections and resource sharing between a range of cybercriminals.Footnote 48

Genesis Market

Genesis Market was a cybercriminal marketplace that sold credentials stolen from millions of compromised computers worldwide. Cybercriminals used Genesis to purchase account access credentials and digital fingerprints, which allowed them to access victims’ online accounts without triggering security warnings. Genesis Market has been linked to millions of financially motivated cyber incidents, including fraud and ransomware attacks,Footnote 49 from its inception in March 2018 until it was disrupted by law enforcement in April 2023.Footnote 50

Fraud and scams remain a persistent threat to Canadians

Figure 8: Losses from

fraud in Canada

(in CAD)Footnote 51

2021: $383 million

2022: $530 million

2023: $567 million

As assessed in NCTA 2023-2024, we judge that fraud and scams are almost certainly the most common form of cybercrime impacting Canadians. Cybercriminals attempt to steal personal, financial, and corporate information using social engineering tactics like phishing.Footnote 52 Phishing is one of the most reported types of fraud in Canada and spear phishing has one of the highest reported levels of financial impact to victims.Footnote 53 For example, spear phishing can lead to compromises that result in the theft of sensitive data and can cause significant financial losses for businesses.Footnote 54

Phishing attacks becoming more accessible and sophisticated with new tools and services

We judge that the threat from fraud and scams will continue to grow in the next two years with the proliferation of Phishing-as-a-Service kits that cybercriminals can purchase online, as well as chatbots powered by artificial intelligence (AI) that craft convincing phishing emails for cybercriminals. These tools make phishing attacks more accessible for cybercriminals who are less technically sophisticated.Footnote 55

Ransomware threat to Canada continues to grow and evolve

Ransomware is one of the most disruptive forms of cybercrime facing Canada and our allies. Since 2020, ransomware attacks have increased in scope, frequency and complexity.Footnote 56 We judge that ransomware will almost certainly continue to be the most impactful cyber threat facing Canadian organizations in the next two years as ransomware actors constantly refine their tactics to maximize profits.Footnote 57

Ransomware incidents and ransom payments are growing

2023 was a record-breaking year for ransomware. By some estimates, the global number of ransomware incidents rose 74% in 2023 compared with 2022,Footnote 58 and global ransom payments reached a record of $1 billion USD.Footnote 59 By one estimate, the average ransom paid in Canada in 2023 was $1.130 million CAD, an increase of almost 150% in two years.Footnote 60 Open-source reporting reveals that these trends continued into the first half of 2024, with ransom payments and incidents on track to exceed numbers observed in 2023.Footnote 61 Observed increases in ransomware are almost certainly higher since many incidents go unreported.Footnote 62 We judge that the ransomware threat will almost certainly continue to grow in the next two years unless significant disruptions to the ransomware ecosystem occur.

Global top ransomware threats 2023

- LOCKBIT: Lockbit is a RaaS cybercrime group that operates a ransomware variant of the same name and has been used to impact a wide range of critical infrastructure entities, including healthcare, energy, and government organizations.Footnote 63

- ALPHV: ALPV is a RaaS cybercrime group that operates the ransomware variant named BlackCat and has been used to impact a wide range of industries, including financial, manufacturing, legal, and professional services organizations.Footnote 64

- CL0P: CL0P is a RaaS operated by the Russian-speaking cybercriminal group TA505 that has been used to impact a wide range of industries by exploiting unpatched software vulnerabilities.Footnote 65

- PLAY: Play is a RaaS cybercrime group operating a ransomware variant of the same name that has been used to impact healthcare and manufacturing organizations.Footnote 66

- BLACK BASTA: Black Basta is a RaaS cybercrime group operating a ransomware variant of the same name that has been used to impact critical infrastructure entities, including healthcare and government organizations.Footnote 67

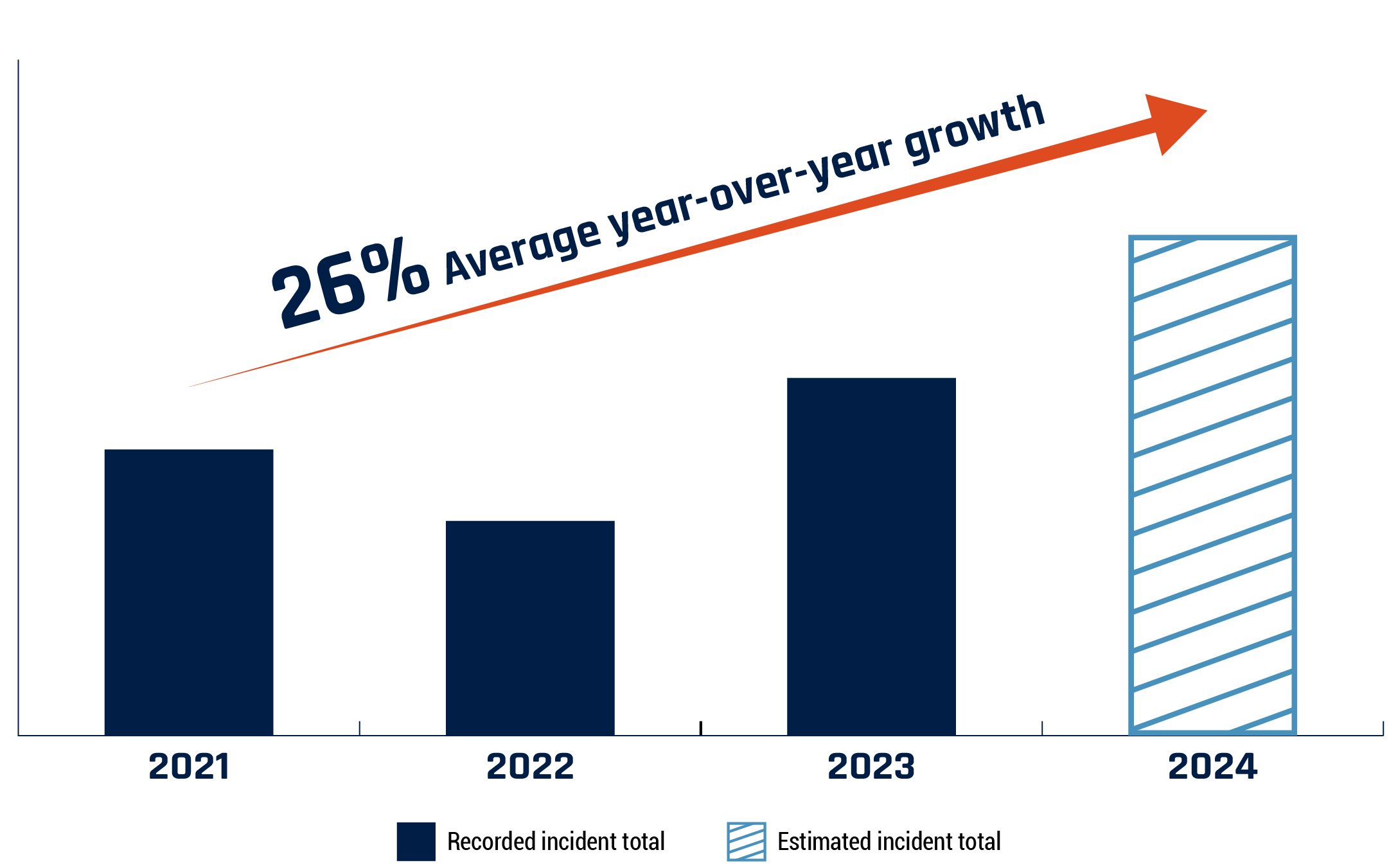

Long description - Figure 9: Relative growth from 2021 of Canadian ransomware incidents known to the Cyber Centre

A bar graph displaying the relative growth from 2021 of Canadian ransomware incidents known to the Cyber Centre by Canadian victims between 2021 and 2024. 2024 numbers are based on projections based on the first six months of data for 2024. Based on our data, ransomware incidents have grown, on average, 26% year-over-year since 2021. This figure displays a temporary drop in ransomware incidents in 2022.

In 2022, we judge that ransomware incidents decreased, in part, due to heightened law enforcement pressure that likely caused some ransomware actors to temporarily pause their activities. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine also likely caused disruptions in the ransomware ecosystem. For example, some ransomware actors likely shifted their focus from financially motivated cybercrime to politically motivated attacks.Footnote 69 However, in 2023, ransomware actors very likely resettled and recovered from those disruptions and elevated their tactics to make up for financial losses from 2022.Footnote 70

Impact of CL0P – Compromises of digital supply chains

Many organizations rely on digital supply chains made up of various vendors for different applications and services. Cybercriminals can turn a breach against a single vendor into cascading incidents impacting multiple victim organizations.Footnote 71 As an example, the spike in global ransomware incidents in 2023 can very likely be partly attributed to CL0P, a ransomware strain operated by Russian-speaking cybercriminals.Footnote 72 CL0P was used to exploit unpatched vulnerabilities in the popular file transfer software applications GoAnywhere and MOVEit. In the MOVEit exploitation alone, CL0P impacted an estimated 2,750 enterprises and 94 million individualsFootnote 73 and amassed approximately $100 million USD in ransom payments.Footnote 74 Because of their profitability, ransomware attacks against digital supply chains will almost certainly continue in the next two years.

Top ransomware groups operate on Ransomware-as-a-Service Model

As highlighted in NCTA 2023-2024, most of the top ransomware groups impacting Canada operate on a Ransomware-as-a-Service (RaaS) business model where a core group of ransomware actors sell or lease their ransomware variant to affiliates who launch attacks. The RaaS ecosystem operates within the wider CaaS ecosystem. It is enabled by a complex supply chain of various actors offering different CaaS services that can be used to carry out ransomware attacks. This includes supporting services that underpin the functioning of the entire ecosystem (see Figure 10).Footnote 75

We judge that the continued popularity of RaaS is almost certainly contributing to the rise in ransomware incidents by lowering the technical barriers to entry for more actors to carry out attacks without needing to develop their own malware.Footnote 76 It is difficult to assess the precise location of ransomware actors. However, we judge that the top ransomware groups impacting Canada have a core membership that is very likely based in countries that make up the former Soviet Union, although their affiliates operate globally.

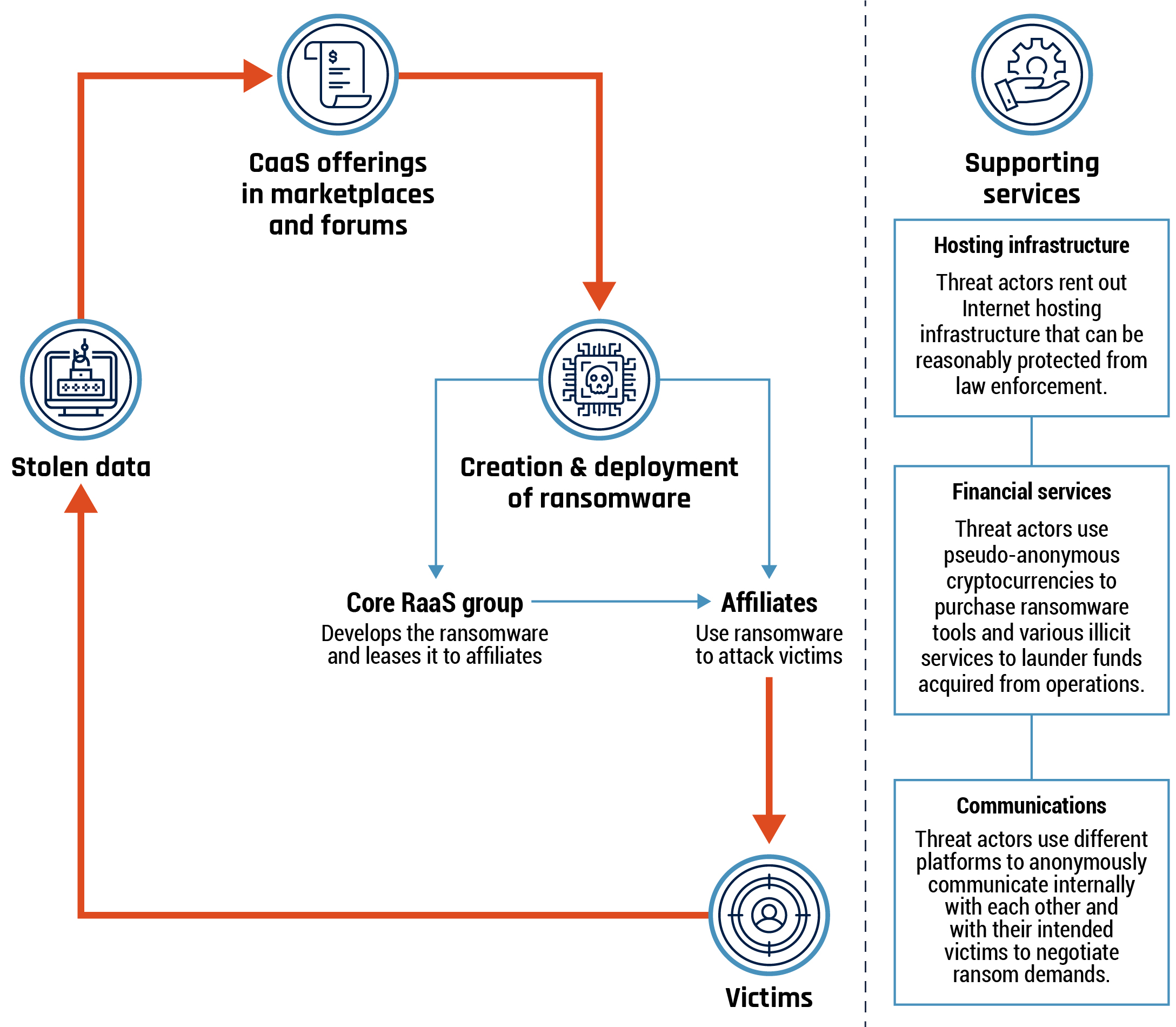

Long description - Figure 10: Ransomware-as-a-Service ( RaaS ) ecosystem

A graphic representing the different parts of the Ransomware-as-a-Service ecosystem and how they all interact to allow cybercriminals to conduct ransomware attacks.

Cybercrime marketplaces and forums provide Cybercrime-as-a-Service offerings, facilitating the creation and deployment of ransomware. Core RaaS groups develop the ransomware and lease it to affiliates through marketplaces and forums. Affiliates then use the ransomware to attack victims. Stolen data from ransomware victims ends up back on cybercrime marketplaces and forums, where it is used to enable further cybercriminal activity.

On the right side of the graphic are supporting services that underpin the entire cybercrime ecosystem. These include the following:

- Hosting infrastructure: Threat actors rent out Internet hosting infrastructure that can be reasonably protected from law enforcement

- Financial services: Threat actors use pseudo-anonymous cryptocurrencies to purchase ransomware tools and various illicit services to launder funds acquired from operations

- Communications: Threat actors use different platforms to anonymously communicate internally with each other and with their intended victims to negotiate ransom demands

Ransomware is impacting Canada’s critical infrastructure

We assess that ransomware actors are almost certainly opportunistic and do not target specific industries. In the last few years, a wide range of Canadian businesses have been impacted by ransomware incidents, including large retailers and educational institutions. These incidents demonstrate that no entity is immune from the threat of ransomware. However, ransomware is almost certainly the top cybercrime threat facing Canada’s critical infrastructure because it can immobilize critical business operations, destroy or damage important business data, and reveal sensitive information.Footnote 77 In addition to the financial losses associated with system repairs and operational disruptions, ransomware attacks can disrupt critical services that put victims’ physical safety and emotional wellbeing in jeopardy.Footnote 78

Critical infrastructure is an attractive target for ransomware actors because these entities are perceived as being more willing to pay large ransoms to prevent disruptions to critical operations. In 2021, ransomware incidents impacting Colonial Pipeline in the U.S. and the JBS Foods operations in North America and Australia resulted in multimillion-dollar payouts for ransomware actors.Footnote 79

According to cyber security reporting , victims in 2023 were becoming less likely to pay ransom demands.Footnote 74 We judge that the perceived opportunities to earn high profits, combined with victims’ reduced willingness to pay, has almost certainly encouraged more technically sophisticated ransomware groups to elevate their extortion techniques and hire skilled affiliates capable of targeting critical infrastructure entities to extract larger ransom payouts.Footnote 80 This is called “big game hunting,” and we judge that it is the primary strategy used by many of the most prolific ransomware groups impacting Canada.Footnote 52

Figure 11: Cyber incidents impacting Canada’s critical infrastructure

Canada’s critical infrastructure sectors have been impacted by various cyber incidents, including ransomware incidents and network breaches, that resulted in disruptions to critical business functions.

Energy sector

June 2023: Suncor Energy experienced a cyber incident that affected the company’s Petro-Canada subsidiary. This temporarily impacted credit and debit processing at retail gas stations across Canada.Footnote 81

Healthcare sector

December 2022: SickKids hospital in Toronto experienced a ransomware incident by an affiliate of the LockBit ransomware group. The impact of the incident was minimal and LockBit issued a public apology and offered to share the decryptor with the hospital.Footnote 82

October 2023: 5 hospitals in Southern Ontario were impacted by a ransomware incident carried out by a ransomware group called Daixin. The incident impacted the hospitals’ information technology (IT) provider, forcing the hospitals to temporarily shut down internal health systems. It resulted in the theft of sensitive files and caused delays in patient care.Footnote 83

February 2024: LockBit reportedly claimed responsibility for a ransomware incident affecting Canadian pharmacy chain London Drugs, which forced the company to temporarily close some of its stores in Western Canada.Footnote 84

Government sector

June 2023: The Government of Nova Scotia was impacted by CL0P’s global exploitation of the MOVEit file transfer system. This resulted in a breach of personal information for an estimated 100,000 current and past provincial government employees.Footnote 85

September 2023: Brookfield Global Relocation Services, which assists Canadian military and foreign service personnel with relocations, was subject to an unauthorized access breach that impacted information about Government of Canada personnel.Footnote 86

March 2024: The City of Hamilton was subject to a ransomware incident that impacted IT systems that manage various municipal functions, such as city phone lines, for weeks.Footnote 87

Ransomware incidents hitting the healthcare sector are on the rise

Ransomware incidents impacting the healthcare sector have been steadily increasing worldwide.Footnote 88 Canada and our allies have collectively experienced high-profile ransomware attacks against the healthcare sector in recent years. In March 2024, Change Healthcare paid a multimillion-dollar ransom for the restoration of sensitive medical data after a ransomware attack disrupted billing processes for prescriptions in pharmacies across the U.S.Footnote 89 Soon after, in June 2024, a ransomware incident impacting pathology firm Synnovis caused major delays to several London, UK hospitals and resulted in the theft of sensitive data, which ransomware actors published online.Footnote 90

By one estimate, ransomware incidents impacting the healthcare sector have nearly doubled since 2022.Footnote 88 This is concerning since these incidents directly disrupt the healthcare sectors’ ability to deliver critical services to patients.Footnote 91 However, we judge that ransomware actors will almost certainly continue to choose victims based on opportunity rather than specific targeting in the next two years. Any observed increases in ransomware incidents impacting the healthcare sector will almost certainly reflect an increase in ransomware incidents overall, as well as the continued use of big game hunting by major ransomware groups.

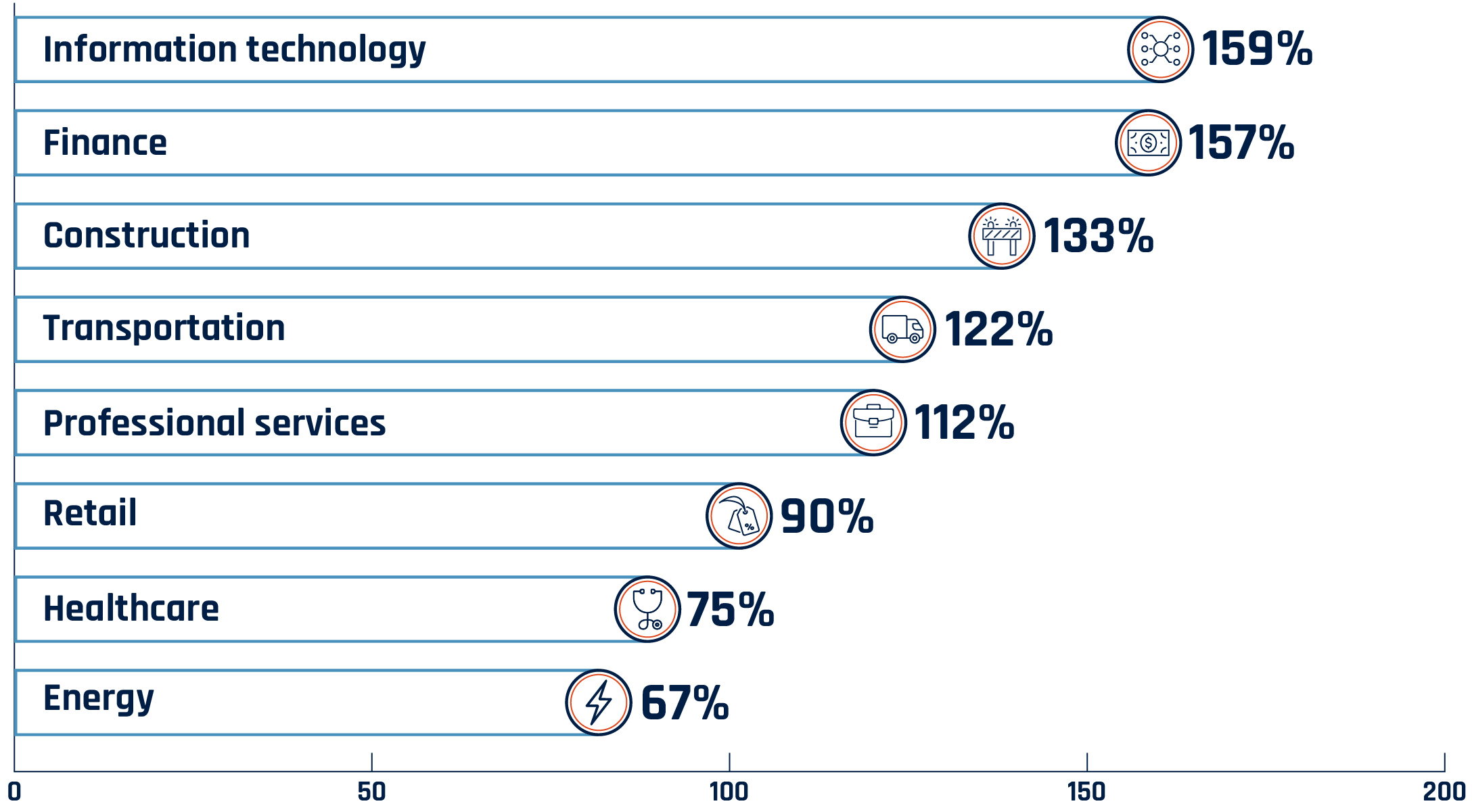

Long description - Figure 12: Increase in Canadian ransomware incidents by sector observed by the Cyber Centre from 2022 to 2023

A bar graph displaying the increase in ransomware incidents observed by the Cyber Centre between 2022 and 2023, broken down by sector:

- Information technology: 159%

- Finance: 157%

- Construction: 133%

- Transportation: 122%

- Professional services: 112%

- Retail: 90%

- Healthcare: 75%

- Energy: 67%

Sector categorizations are partially derived from the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS).

Ransomware actors are evolving their tactics to boost profits and evade detection

Ransomware actors are constantly evolving their strategies and adapting their techniques to maximize their profits and evade law enforcement detection.Footnote 92 We judge that these financial incentives combined with the flexibility of the RaaS model have almost certainly bolstered ransomware actors’ resiliency in the face of law enforcement disruptions.

Ransomware ecosystem is splintering under law enforcement pressure

Recent major international law enforcement operations to tackle the ransomware ecosystem almost certainly degraded the targeted groups’ capabilities and caused chaos in the cybercriminal underground.Footnote 93 However, we judge that these disruptions almost certainly will not have an enduring impact on the ransomware environment because unless members of core RaaS groups are arrested, actors often find ways to adjust, rebrand and resume their operations.Footnote 94

By that same token, it is almost certain that the CaaS model has made the ransomware ecosystem more resilient to law enforcement action. The complex web of enabling services and cybercriminals interacting in borderless online spaces makes investigating cybercrime difficult.Footnote 95 If law enforcement disrupts a popular CaaS provider, the actor behind it will often rebrand and relaunch their service, or another service will quickly take their place. The flexibility of the CaaS model also makes it easy for cybercriminals to use multiple service providers simultaneously so they can pivot to new service providers if one is disrupted.Footnote 94

International law enforcement disruptions against the ransomware ecosystem

The groups below were major players in the ransomware ecosystem. Prior to their disruptions, these groups were linked to over 1,000 compromises around the world and had amassed millions in ransom payments.Footnote 96

- January 2023: Hive’s networks were infiltrated, decryptor tools were provided to victims to recover their data and Hive’s infrastructure was seized by law enforcement.Footnote 97

- December 2023: ALPHV (also known as BlackCat) had their infrastructure seized by law enforcement and a decryptor tool was provided to victims.Footnote 98

- February 2024: LockBit’s infrastructure was seized by law enforcement and cryptocurrency accounts linked to LockBit were frozen. Some core members were also arrested.Footnote 99

In the next two years, we judge that the ransomware ecosystem will almost certainly become increasingly splintered.Footnote 94 Affiliates will almost certainly begin to act independently and create their own ransomware variants to reduce their susceptibility to law enforcement disruptions.Footnote 100 Further complicating this threat landscape, we judge that smaller ransomware groups will likely begin collaborating to increase their capabilities, or they will try to attract affiliates from ransomware groups that are subject to disruption operations to take the place of their former competitors and grab a greater share of the ransomware market.Footnote 101

Intensifying extortion methods

Ransomware actors are increasing pressure on victims to pay ransoms by ramping up their extortion methods. Some ransomware groups have started posting count downs on their websites indicating when they plan to leak stolen data, or even directly calling victims or their clients and threatening to release their personal information if they do not pay the demanded ransom.Footnote 102 Additionally, ransomware actors have publicly criticized the organizations that have fallen victim to their ransomware to damage their reputation, and have encouraged clients of the victim organizations to file lawsuits against the victims.Footnote 103 Ransomware actors have also started to use new legislation that require victims to report ransomware incidents to apply pressure to their victims. For example, ALPHV affiliated actors claimed that they filed a complaint with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission against a victim for failing to report the ransomware incident that ALPHV itself conducted against them.Footnote 104 We judge that ransomware actors’ extortion methods will continue to evolve in the next two years in an effort to maximize their likelihood of receiving payment from victims.

Ransomware actors are using new tactics to obfuscate their activities

As ransomware actors have come under intense scrutiny from law enforcement, many have started layering obfuscation techniques to camouflage and hide themselves from detection and minimize their digital footprints.Footnote 91

Figure 13: Obfuscation techniques used by ransomware actors

Dual ransomware attacks

Using multiple ransomware strains used in successive attacks against the same target to avoid attribution to the actors responsible for the attack.Footnote 105

Encryption

Remote encryption

Using one compromised device to encrypt data on other devices on the same network to bypass security mechanisms.Footnote 106

Hybrid encryption

Using multiple layers of encryption to make it more difficult for victims to recover their data.Footnote 107

Living off the land

Blending in with normal network operations to move around and escalate privileges within a victim network before encrypting or exfiltrating sensitive data.Footnote 108

Uncommon programming languages

Coding malware using uncommon programming languages to bypass security mechanisms designed to detect more popular programming languages.Footnote 109

Collaboration is necessary to tackle evolving ransomware threat

We judge that ransomware actors will continue to diversify their tactics in response to heightened law enforcement attention. Understanding this threat, the CaaS business model, and recognizing the dynamic nature of this ecosystem will be critical to tackling it in the future. Collaboration between industry, law enforcement, and all levels of government, as well as bolstering Canadians’ awareness about cybercrime, are imperative to building resilience against this evolving threat.Footnote 110

Trends shaping canada’s cyber threat landscape

Background

CSE uses its expertise to help monitor, detect, and investigate threats against Canada’s information systems and networks. Based on our observations since NCTA 2023-2024, we have identified five trends that will shape Canada’s cyber threat environment until 2026:

- Trend 1: Artificial intelligence (AI) technologies are amplifying cyber space threats

- Trend 2: Cyber threat actor tradecraft is evolving to evade detection

- Trend 3: Geopolitically inspired non-state actors are creating unpredictability

- Trend 4: Vendor concentration is increasing cyber vulnerability

- Trend 5: Dual-use commercial services are in the digital crossfire

Trends discussed in past NCTAs are still relevant

Before discussing the five trends above in more detail, it is important to note that trends impacting Canada’s cyber threat landscape that we raised in previous NCTAs remain relevant today. These trends continue to evolve over time in light of geopolitical, technological, and threat actor developments. For example:

- The cyber threat surface keeps expanding: In addition to the continued adoption and deployment of the Internet of Things (e.g., connected vehicles), the boom in cloud-based AI platforms and services is forecasted to drive demand for supporting infrastructure, such as AI -capable data centres and energy generation, and lead to the transfer of even more data to cloud environments. It is also very likely that AI -focused organizations (including AI labs that conduct AI research and develop AI models) are now more prominent targets for cyber threat actors.Footnote 111

- Supply chain attacks continue: Cyber threat actors continue to launch digital supply chain attacks where a threat actor compromises or exploits a software, information technology (IT), or cloud services vendor to enable it to exploit the customers that use the service. This includes double supply chain attacks where one supply chain attack enables another.Footnote 112

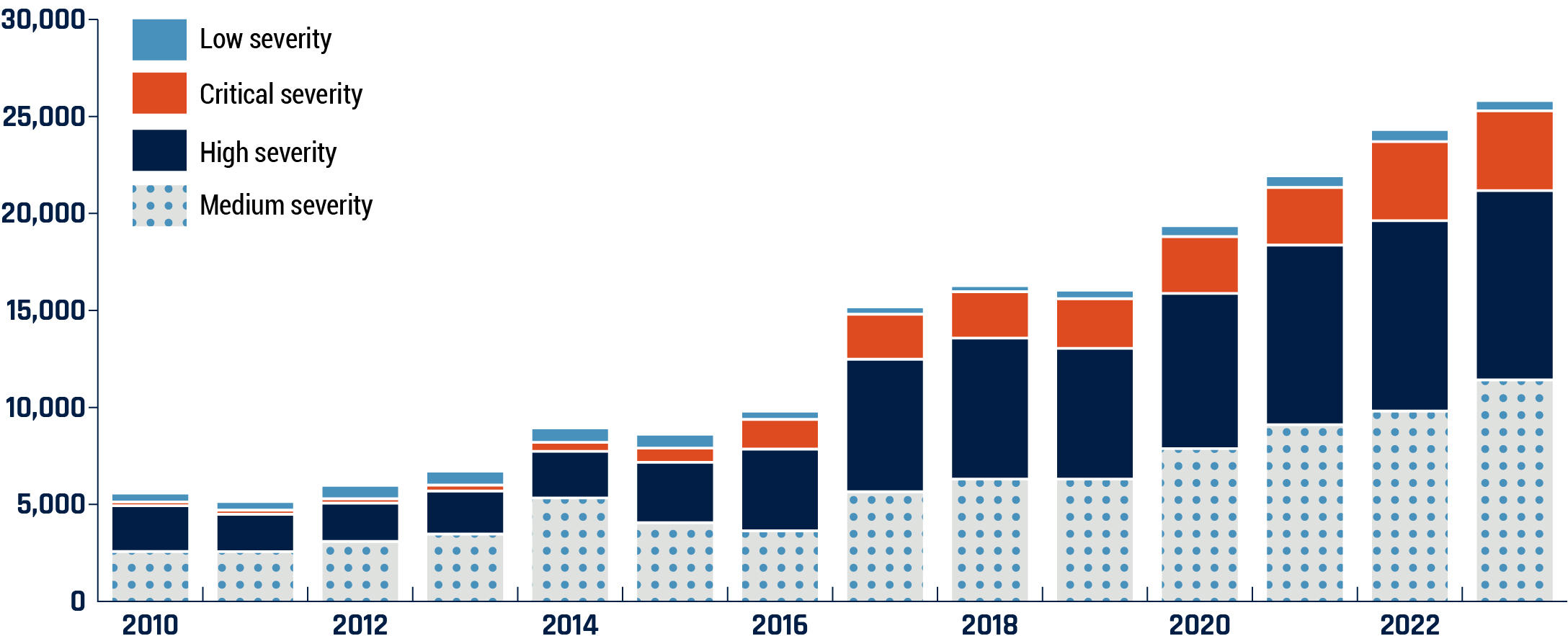

- Publicly known vulnerabilities are still being exploited: Cyber threat actors are constantly scanning for publicly known security vulnerabilities in software and exploiting unpatched vulnerabilities to gain unauthorized access to private and public networks. The number of common vulnerabilities and exposures (CVE) continues to grow (Figure 14). The time it takes threat actors to exploit these vulnerabilities continues to decrease, with attacks starting within days after their disclosure.Footnote 113

Long description - Figure 14: Common vulnerabilities and exposures (CVE) count by severity

A bar graph displaying the number of reported common vulnerabilities and exposures by severity by year.

| Year | Low severity | Medium severity | High severity | Critical severity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 304 | 2,493 | 2,208 | 42 |

| 2011 | 287 | 2,491 | 1,769 | 61 |

| 2012 | 537 | 3,016 | 1,821 | 66 |

| 2013 | 563 | 2,296 | 2,060 | 156 |

| 2014 | 590 | 5,255 | 2,250 | 310 |

| 2015 | 559 | 3,978 | 2,961 | 578 |

| 2016 | 270 | 3,559 | 4,060 | 1,380 |

| 2017 | 228 | 5,574 | 6,681 | 2,163 |

| 2018 | 157 | 6,229 | 7,113 | 2,235 |

| 2019 | 289 | 6,231 | 6,583 | 2,405 |

| 2020 | 410 | 7,800 | 7,846 | 2,774 |

| 2021 | 442 | 9,035 | 9,103 | 2,818 |

| 2022 | 467 | 9,733 | 9,662 | 3,918 |

| 2023 | 379 | 11,341 | 9,602 | 3,960 |

Trend 1: Artificial intelligence technologies are amplifying cyberspace threats

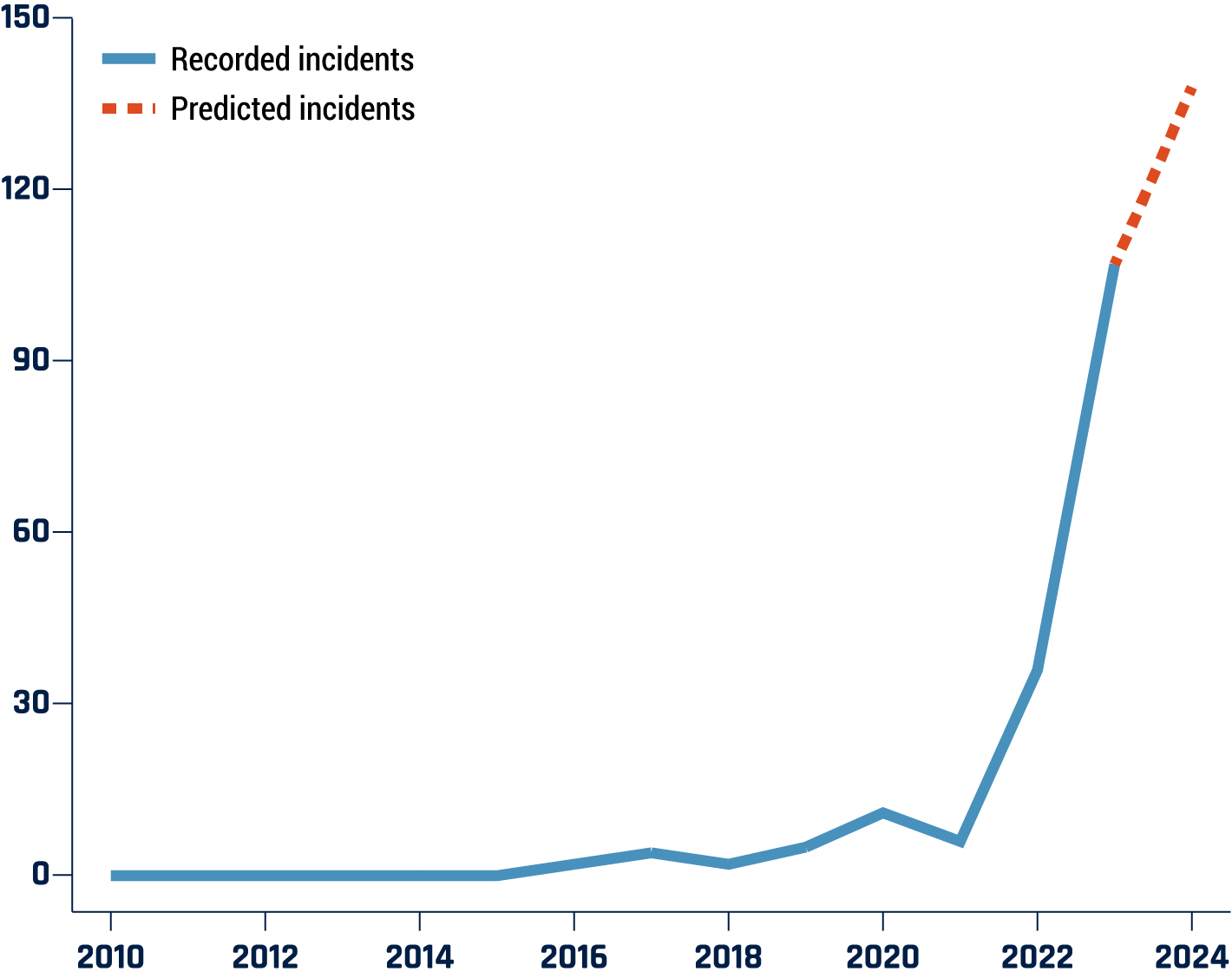

AI technologies are almost certainly lowering the barriers to entry and enhancing the quality, scale, and precision of malicious cyber threat activity.Footnote 115 Cybercriminals and state-sponsored cyber threat actors are using generative and predictive AI tools (including large language models (LLMs)) to support their work processes, from content generation to big data analysis. We assess that technically skilled cyber threat actors will almost certainly attempt to misuse AI tools in novel ways over the next two years as the technology develops. This includes automating parts of the cyber attack chain to improve productivity.Footnote 116

Long description - Figure 15: Publicly reported worldwide generative AI incidents resulting in harm or near harm

A line graph depicting the rise in the number of publicly reported generative AI incidents resulting in harm or near harm worldwide. The data represented is from 2010 to 2024. The predicted total number of incidents for 2024 is indicated by a dotted line and is based on data from the first six months of the year.

| Year | Incident count |

|---|---|

| 2010 | 0 |

| 2011 | 0 |

| 2012 | 0 |

| 2013 | 0 |

| 2014 | 0 |

| 2015 | 0 |

| 2016 | 2 |

| 2017 | 4 |

| 2018 | 2 |

| 2019 | 5 |

| 2020 | 11 |

| 2021 | 6 |

| 2022 | 36 |

| 2023 | 107 |

| 2024 | 138 |

AI is improving the personalization and persuasiveness of social engineering attacks

Cybercriminals and state-sponsored cyber threat actors are almost certainly using LLMs to improve social engineering attacks that manipulate targets into doing something that is detrimental to their interests, such as disclosing sensitive information, authorizing fraudulent transactions, or downloading malware.Footnote 118 Generative AI tools enable cyber threat actors to create realistic audio and visual content impersonating trusted individuals (i.e., deepfakes). These help to establish legitimacy with and persuade targets.Footnote 119 Cyber threat actors are also using AI to craft personalized phishing emails at scale with convincing and grammatically correct language that mimics human writing styles, making it harder for recipients to identify and filter phishing attempts.Footnote 120

AI technologies are enhancing the quality and scale of foreign online influence campaigns

In NCTA 2023-2024, we discussed how state cyber threat actors can create and spread AI -generated disinformation. Since then, a growing number of countries, including the PRC , Russia, Iran, and Israel, have reportedly incorporated fake or deceptive AI -generated articles, images, and videos (deepfakes) in their online influence operations (misinformation, disinformation, and malinformation) to enhance the quality and scale of their campaigns.Footnote 121 They are also very likely using AI tools to generate fictitious social media bot accounts and online personas in an effort to amplify engagement.Footnote 122 These campaigns are designed to weaken opponents by polluting the online information space, undermining trust in institutions, and sowing doubt and division in the target society.Footnote 123

We assess that AI -enhanced disinformation is more likely to gain traction when it has one or more of these characteristics:Footnote 124

- amplifies polarizing narratives that already exist in the target society

- fills a void in the information space

- is spread by a trusted or official source(s)

- targets time-sensitive situations when there is limited time to debunk fake content

The rise of AI -generated websites

Foreign states are creating fake news websites masquerading as real news outlets as part of their disinformation campaigns. Many of the sites are designed to look like local news outlets that have closed down and rely on AI -generated content.Footnote 125

Predictive AI is improving big data analysis capabilities

Well-resourced states are very likely leveraging AI tools to help process and analyze large volumes of data they collect. We assess that foreign intelligence services are very likely using AI -enabled data analytics to find patterns and trends in bulk data, gain insights on individuals and assets of interest, and inform follow-on cyber operations.Footnote 126

Trend 2: Cyber threat actor tradecraft is evolving to evade detection

As network defences have improved at detecting and responding to security threats, cyber threat actors are evolving their tradecraft in an attempt to minimize detection and stay hidden operating on victim systems longer.

Cyber threat actors are targeting and exploiting edge devices to access networks

Attacker dwell time is dropping

The global median dwell time – number of days an attacker is present in a compromised system before detection – continued to drop from 2022 to 2023.

MandiantFootnote 127

Cyber threat actors are exploiting vulnerabilities in security and networking devices that sit at the perimeter of networks—known as “edge” devices (e.g., routers, firewalls, and virtual private network ( VPN ) solutions). By compromising an edge device, a cyber threat actor can enter a network, monitor, modify, and exfiltrate network traffic flowing through the device, or possibly move deeper into the victim’s network.

Cyber threat actors very likely target edge devices because network defenses may have limited capability to monitor and detect malware activity on them, especially compared to other access vectors, such as phishing emails.Footnote 128 For example, in early 2024, Canada and our allies detected that a well-resourced and sophisticated state-sponsored cyber threat actor had collected and exfiltrated data by exploiting 2 newly discovered vulnerabilities in VPN devices used by government and critical national infrastructure networks.Footnote 129

Cyber threat actors are “living off the land” in compromised environments to stay undetected

Cyber threat actors using living-off-the-land (LOTL) techniques repurpose native system tools and processes that are already present in the target’s environment to move throughout the network discreetly.Footnote 130 They do not deploy malware or custom tools on the compromised network. This makes it challenging for network defences to detect and discover intrusions.Footnote 131PRC , Russian, and Iranian state-sponsored cyber threat actors use LOTL techniques.Footnote 8 For example, a Russian cyber threat actor reportedly compromised a Ukrainian electric utility’s network in October 2022 and used LOTL techniques to move through the utility’s operational technology environment before triggering a power outage.Footnote 132

Cyber threat actors are abusing domestic infrastructure to hide their malicious activity

State-sponsored cyber threat actors and cybercriminals are almost certainly conducting malicious activity against Canada using virtual resources and networking infrastructure (e.g., routers) located in North America to limit scrutiny and visibility into their operations.Footnote 133 For example, Russian and PRC state-sponsored cyber threat actors have been observed routing their malicious cyber operations through compromised small office and home office (SOHO) network equipment located in Canada and the U.S., such as routers belonging to unsuspecting households and businesses, to blend into normal network activity.Footnote 134

Trend 3: Geopolitically inspired non-state actors are creating unpredictability

Geopolitical conflicts and tensions are inspiring disruptive cyber threat activity from non-state groups, commonly referred to as hacktivists. Geopolitically motivated hacktivists typically conduct attacks to gain attention, such as DDoS attacks, website defacements, and data leaks. Some groups have elevated the impact of their activity by opportunistically targeting and disrupting vulnerable critical infrastructure, such as municipal water systems, risking serious harm to the public.Footnote 135

Geopolitically motivated hacktivism is surging around military conflicts. Hacktivist groups have carried out campaigns related to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022 and the Israel-Hamas war in 2023.Footnote 136 Diplomatic tensions are also inspiring hacktivist activity. After Canada accused India of involvement in the killing of a Canadian citizen, a pro-India hacktivist group claimed to have defaced and conducted brief DDoS attacks against websites in Canada, including the public-facing website of the Canadian Armed Forces.Footnote 137

This non-state ecosystem is dynamic and unpredictable. Some hacktivists are genuinely motivated by a mix of patriotism, ideology, or a political cause, but others opportunistically take advantage of conflicts for personal benefit or notoriety. New groups regularly appear and established groups dissolve and re-emerge with new names. Actors shift their focus and motivations. Different groups coordinate and collaborate, including across multiple conflicts.Footnote 138 Although hacktivist activities can sometimes align with an adversarial state’s interests, the relationship, if any, between a hacktivist and the state can be difficult to discern.

Trend 4: Vendor concentration is increasing cyber vulnerability

The provision of many technology services is concentrated, with only a few large providers of a given digital service, each with a large base of users.Footnote 139 Organizations in both the public and private sectors, including banks, airlines, and healthcare providers, rely on these dominant service providers, such as a cloud provider or a specialized Software-as-a-Service platform, to support critical functions and operations.Footnote 140 A cyber incident impacting a single dominant service provider can impact an entire sector.