Alternate format: Ransomware Threat Outlook 2025-2027 (PDF, 1.8 MB)

Executive summary

This assessment is an update to the Canadian Centre for Cyber Security's (Cyber Centre) Baseline cyber threat assessment: Cybercrime, published in 2023. It is intended to provide an update on the ransomware threat to Canada and to inform Canadian organizations about the early history of ransomware, emerging and projected trends, and ransomware’s impact on Canada and Canadian organizations. It will also debunk common myths and misconceptions on cyber hygiene and responding to cyber incidents. While this report is intended to inform Canadian organizations of all sizes, including public sector entities and critical infrastructure, all Canadians can benefit from reading this report and increasing their knowledge of the ransomware ecosystem.

For the purposes of this assessment, ransomware generally refers to a type of malware that denies a user access to a system or data until a sum of money is paid. However, the Cyber Centre recognizes that ransomware has evolved to also include incidents where data theft and extortion are used in place of encryption.

Ransomware emerged as an informal method of cybercrime that used basic encryption and extortion. However, it has quickly evolved over the past decades into an interconnected and sophisticated ecosystem where threat actors communicate and conduct payments through borderless online spaces that are difficult to access on the dark web.

We assess that threat actors carrying out ransomware attacks impacting Canadian organizations are almost certainly opportunistic and financially motivated. All Canadian organizations, regardless of size or sector, are at risk of being targeted by ransomware. In addition to impacting the infrastructure, data, supply chain, and operations of organizations, a ransomware attack can also impact Canadians’ livelihoods by disrupting the critical services they depend on.

Assessment base and methodology

The key judgments in this assessment rely on reporting from multiple sources, both classified and unclassified. The judgments are based on the knowledge and expertise in cyber security. Defending the Government of Canada’s information systems provides the Cyber Centre with a unique perspective to observe trends in the cyber threat environment, which also informs our assessments. The Communications Security Establishment Canada’s (CSE) foreign intelligence mandate also provides valuable insight into adversary behaviour in cyberspace. While we must always protect classified sources and methods, we provide the reader with as much justification as possible for our judgments.

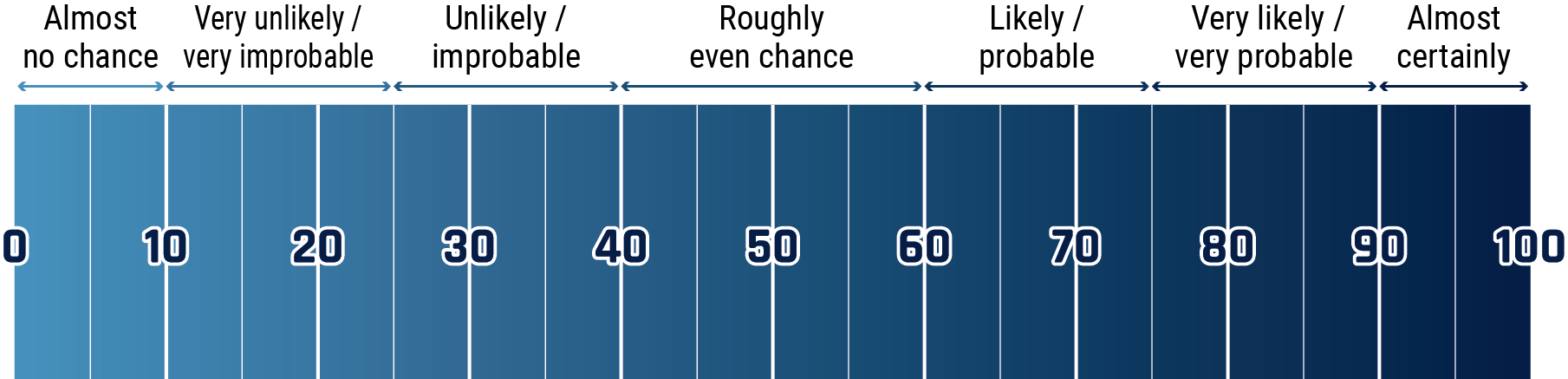

Our judgments are based on an analytical process that includes evaluating the quality of available information, exploring alternative explanations, mitigating biases and using probabilistic language. We use the terms “we assess” or “we judge” to convey an analytic assessment. We use qualifiers such as “possibly,” “likely,” and “very likely” to convey probability.

Assessments and analyses in this report are based on information available as of September 4, 2025.

Estimative language

The chart below matches estimative language with approximate percentages. These percentages are not derived via statistical analysis but are based on logic, available information, prior judgments, and methods that increase the accuracy of estimates.

Long description - Estimative language chart

- 1 to 9% Almost no chance

- 10 to 24% Very unlikely/very improbable

- 25 to 39% Unlikely/improbable

- 40 to 59% Roughly even chance

- 60 to 74% Likely/probably

- 75 to 89% Very likely/very probable

- 90 to 99% Almost certainly

About the Cyber Centre

The Cyber Centre is Canada’s technical and operational authority on cyber security. Part of CSE, we are the single unified source of expert advice, guidance, services, and support on cyber security for Canadians and Canadian organizations. The Cyber Centre works in close collaboration with Government of Canada departments, critical infrastructure, Canadian businesses, and international partners to prepare for, respond to, mitigate, and recover from cyber events. The Cyber Centre is outward-facing and welcomes partnerships that help build a stronger, more resilient cyberspace in Canada. In line with the National Cyber Security Strategy, the Cyber Centre represents a more cooperative approach to cyber security in Canada. The Cyber Centre helps raise Canada’s cyber security bar so that Canadians can live and work online safely and with confidence.

Message from the Head of the Cyber Centre

At a time when cybercriminals continue to target Canadian businesses, critical infrastructure, and government systems, education on these threats has never been more important. As Canada’s national authority on cyber security, the Cyber Centre is committed to helping Canadians understand, prepare for, defend against, and respond to the digital threats that impact our economy, our institutions, and our daily lives.

Among these threats, ransomware continues to stand out as one of the most disruptive, costly, and persistent challenges facing Canadian organizations of every size. This is why this report, the Ransomware Threat Outlook 2025 to 2027, provides a forward-looking view of the ransomware landscape we anticipate in the next 2 years. Our analysis draws on reporting from across Canada and around the world, classified intelligence from our foreign partners, and insights from the private sector. Together, these perspectives let us identify not only the tools, tactics, and procedures of today’s most prolific cybercrime operators, but also the likely trends and evolutions that will define this threat tomorrow.

As you will read in this report, ransomware is big business. Despite some concerning trends, Canadians can rest assured that the Cyber Centre is keeping pace to address these threats and is developing new tools to defend Canadian networks and systems.

Our objectives are clear: to equip decision makers with the knowledge they need to manage their risk, to strengthen Canada’s resilience, and to safeguard the trust Canadians place in our digital systems. Only by working together can we blunt the impact of ransomware and ensure Canada is secure and resilient in an ever-evolving cyber landscape.

In partnership,

Rajiv Gupta

Head, Canadian Centre for Cyber Security

Key judgments

- The ransomware threat in Canada continues to increase and evolve quickly. Threat actors are leveraging various sophisticated tactics to carry out cybercrime. We assess that ransomware actors operating against Canadian targets are almost certainly opportunistic and financially motivated. All organizations, as well as individuals, in Canada almost certainly risk being targeted by ransomware at some point and should bolster their cyber resilience accordingly.

- Ransomware threat actors have demonstrated adaptability to changes in the digital landscape and will very likely continue leveraging advancements in areas like artificial intelligence (AI) and cryptocurrency while developing new extortion tactics to increase their financial reward.

- We assess that basic cyber hygiene practices like regular software updates, implementing multi-factor authentication (MFA) and backups, and being cautious of phishing attempts continue to help Canadians and Canadian organizations strengthen their baseline cyber threat readiness. Cyber security practices are not just an optional extension of one’s business. They are integral to protecting critical data and operations, and to safeguarding Canadians who are reliant on the services of organizations responsible for this data.

- Understanding and mitigating the ransomware ecosystem requires continued cooperation and diligence among law enforcement, government agencies, private organizations, and the Canadian public. We assess that threat actors carrying out ransomware attacks will remain a significant threat to Canada in the next 2 years.

The threat ecosystem

Between the 1990s and the 2020s, cybercrime changed drastically, bringing about significant shifts in how threat actors and Canadians engage with one another. Understanding the evolution of ransomware provides insight into how cybercriminals take advantage of technological advancements and how changes in the ecosystem have increased the prevalence and pervasiveness of cyber threats. It also helps identify key indicators for future trends.

The evolution of ransomware

- 1989: Harvard professor, Dr. Joseph L. Popp sent around 20,000 malware-infected floppy disks that used symmetric cryptography to encrypt file names to AIDS researchers in 90 countries. Victims were instructed to send a cheque of up to $378 to a post office box in Panama to receive a decryptor disk to restore their systems. The only individuals who reportedly paid the ransom were investigators. Dr. Popp was arrested and charged with blackmail. This was one of the first documented ransomware attacks. However, following Dr. Popp’s arrest, ransomware incidents remained relatively uncommon until the widespread adoption of the Internet in the 21st century.Footnote 1

- 2009: The emergence of Bitcoin in 2009 as the first decentralized cryptocurrency, and the surge in popularity of alternative cryptocurrencies in the subsequent years, significantly enhanced cybercriminals’ ability to process payments and launder money from illicit online activities. By providing threat actors with avenues for untraceable funds, Bitcoin helped ransomware become a profitable industry.Footnote 2

- 2012: The Reveton ransomware was deployed as a malware that installs itself on a victim’s network when they click on a compromised website. The ransomware impersonated law enforcement agencies purporting to have seized control of the device due to the user’s supposed criminal online activity. Victims were threatened with jail time and were ordered to pay a ransom through a prepaid debit card. According to open-source reporting, the operators of Reveton sold the malware to third parties, increasing the number of victims. This marked the first reported occurrence of Ransomware-as-a-Service (RaaS).Footnote 3

- 2013: The CryptoLocker ransomware first infected Windows computers in September 2013, using malicious attachments in spam and phishing emails as the primary method of delivery. CryptoLocker was one of the first ransomware variants to use sophisticated encryption. Once a device was encrypted, a ransom note would appear, ordering victims to pay a sum to regain access to their files. Cryptocurrency was included as a payment option. The FBI reports that within the first 2 months of operation, the threat actor group had amassed over USD 27 million in ransom. CryptoLocker was distributed through the GameOver Zeus botnet, which was attributed to a Russian cybercriminal. In June 2014, a multinational law enforcement collaboration announced that it successfully disrupted the GameOver Zeus botnet and seized CryptoLocker servers.Footnote 4

- 2015: The group behind the SamSam ransomware emerged as the first group to consistently engage in targeted attacks against critical infrastructure and larger corporations, including government entities and healthcare organizations in the United States and Canada. This behaviour is now commonly known as “big game hunting” since critical infrastructure and other sensitive organizations are perceived to be more likely to pay larger ransom demands to avoid critical service disruptions or protect sensitive information. In 2018, 2 Iranian men were indicted in the United States on federal charges for deploying the SamSam ransomware to over 200 victims and causing over USD 30 million in lossesFootnote 5.

- 2017: The May 2017 WannaCry attack was publicly identified as the fastest-spreading and largest-scale global ransomware incident at the time. Once a device was infected, WannaCry—which exploited a Microsoft vulnerability—spread rapidly through a network, infecting other vulnerable machines without human interaction. Although Microsoft had patched the vulnerability months prior, users who failed to install the update were susceptible to the attack. In a single day, the attack infected over 230,000 computers in 150 countries, bringing unprecedented global attention to ransomware.Footnote 6

- 2019: After an American security company failed to meet payment deadlines set by the Maze ransomware group, the group published around 700 MB of the company’s stolen data on their dedicated leak site to increase pressure on the company to comply with the ransom demand. This is the first known instance of a ransomware group publicly releasing victim data and using double extortion methods. Threat actors publishing sensitive corporate information also eliminated backups as an effective sole mitigation tacticFootnote 7.

- 2020s: The popularization of RaaS and the development of affiliate-based business models that license malware and distribute profits has lowered the technical barriers to entry for cybercriminals. The rise of initial access brokers has also increased the efficiency of active ransomware groups. By selling network access to threat actors, these brokers reduce the time required to execute an attack. The spread of secure communication platforms and dark web marketplaces and forums has also enhanced threat actors’ ability to actively sell their services, network with cybercriminals, and engage with victims.Footnote 8

The modern ransomware landscape

The modern ransomware landscape is a highly sophisticated and interconnected threat ecosystem that is constantly evolving. Understanding current and emerging trends in the ransomware landscape can help Canadians recognize and better prepare for ransomware risks.

Multi-extortion ransomware attacks

As Canadian organizations expand and bolster their baseline cyber resilience, cybercriminals continually look to modify and adapt their tradecraft to best extort victims across their entire supply chain. We assess that the transition from single extortion to multi-extortion methods is indicative of cybercriminals’ increased sophistication and of their motivation to increase both the impact of their attacks and the likelihood of victims paying the ransom.

According to open-source reporting, potential multi-extortion strategies include distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks and contacting third-party entities associated with an organization—including its suppliers, partners, or customers—for ransom.Footnote 9 In addition to financial losses and sensitive data leaks, multi-extortion attacks can damage an organization’s reputation due to service outages or the revictimization of victims.

Exfiltration-only attacks

Although most ransomware groups will likely continue to use encryption in their ransomware, we assess that the trend of threat actors adopting exfiltration-only attacks is a notable shift in behaviour. In November 2024, the ransomware group Hunters International focused primarily on exfiltration-only attacks and extortion.Footnote 10 In January 2025, Hunters International very likely rebranded to World Leaks, an extortion-based group that provides its custom-built data exfiltration tool to affiliates for them to use against victims.Footnote 11 Open-source reporting attributes the growing trend toward exfiltration-only attacks to how quickly and simply these attacks can be deployed and executed compared with encryption-based attacksFootnote 12.

Evolutions in victim demography

Critical infrastructure and large corporations remain attractive targets for ransomware actors. However, based on recent developments in victim demography, we assess that no organization is immune to cyber incidents. Businesses with fewer cyber security resources may face more challenges in responding to sophisticated ransomware attacks.

Ransomware actors often leverage initial access points such as unpatched software, compromised credentials, phishing, or remote desk protocol. This can generate particular vulnerabilities for entities with minimal capabilities to invest in information technology (IT) infrastructure or cyber security training for employees.Footnote 13

The impacts of ransomware—including operational downtime, supply chain delays, diminished consumer trust and recovery costs—can have serious impacts on small and medium businesses and could be the deciding factor on whether these businesses are able to remain commercially viable.Footnote 14 Organizations with few internal cyber security specialists also often hire third-party managed service providers (MSPs) to handle IT and information management services. Because of their expansive client networks and access to sensitive information, MSPs are attractive targets for cybercriminals.Footnote 15

Artificial intelligence

We assess that, as AI becomes more sophisticated and more integrated into Canadian organizations, some cybercriminals will almost certainly adopt AI capabilities to target victims and lower technical barriers to entry into the ransomware ecosystem. Threat actors have been leveraging improvements in generative AI, particularly large language models, across various stages of ransomware attacks, including:

- developing malware

- generating deepfakes

- automating negotiations with victims

- conducting vulnerability research

- implementing social engineering strategies

This contributes to reducing the skill and resource constraints that cybercriminals typically face.Footnote 16

Decentralized finance and cryptocurrency

We assess that ransomware actors will continue to leverage cryptocurrency because of the anonymity it offers compared with mainstream financial assets. Increased regulatory pressures and law enforcement action against virtual financial crimes have further encouraged threat actors to find ways to hide their transactions.Footnote 17

Cryptocurrency helps cybercrime profits transcend borders, increasing the scope of threat actors’ illicit activities and posing challenges for law enforcement investigations. In 2023, the Financial Transactions and Reports Analysis Centre of Canada stated that the movement of proceeds derived from fraud and ransomware attacks is the most prevalent form of money laundering involving virtual currencies.Footnote 18

Virtual assets

- Cryptocurrency

- Cryptocurrencies are digital tokens that depend on cryptographic techniques to pseudo-anonymously transfer funds through a public ledger (blockchain) that records transactions between cryptocurrency wallet addresses. Cybercriminals often use cryptocurrency like Bitcoin (BTC) for illicit transactions.Footnote 19

- Privacy coins

- Privacy coins are a type of cryptocurrency that provide greater anonymity because they operate on their own blockchain to conceal users’ identities and transaction histories. Examples include Monero (XMR), Zcash (ZEC), and Dash (DASH)Footnote 20.

Obfuscation and laundering techniques

- Chain hopping

- Chain hopping is when cybercriminals transfer funds from one blockchain to another to obfuscate the funds’ illicit origins.Footnote 21

- Mixers

- Mixers are services that break links between the original and final address of cryptocurrency funds to hide the funds’ illicit originsFootnote 22.

Geopolitical influence on ransomware

Geopolitical conflicts are increasingly extending into the digital environment as more governments engage in cybercrime, including ransomware, as an alternative means to retaliate against adversaries or bypass international sanctions. Cybercriminal engagement varies by state: some states provide resources and protection to cybercriminals directly while others quietly permit cybercrime as long as it aligns with their political interests and does not impact victims within their country.Footnote 23

During the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022, the ransomware group Conti publicly threatened to retaliate against Western countries that launched cyber attacks against Russian critical infrastructure.Footnote 24 According to open-source reporting, amid ongoing conflict in the Middle East, a ransomware group linked to the Islamic Republic of Iran began offering higher proceeds to actors who engaged in cyber attacks on Iran’s adversaries.Footnote 25

The Cyber Centre continues to monitor how geopolitics impact cybercrime and the degree to which state actors engage with cybercriminals in pursuit of their countries’ strategic objectives.

The state of ransomware in Canada

The majority of the top ransomware groups impacting Canada are almost certainly financially motivated and opportunistic. We assess that the core membership of these groups is most likely Russian speaking and operating out of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), although their affiliates operate globally.

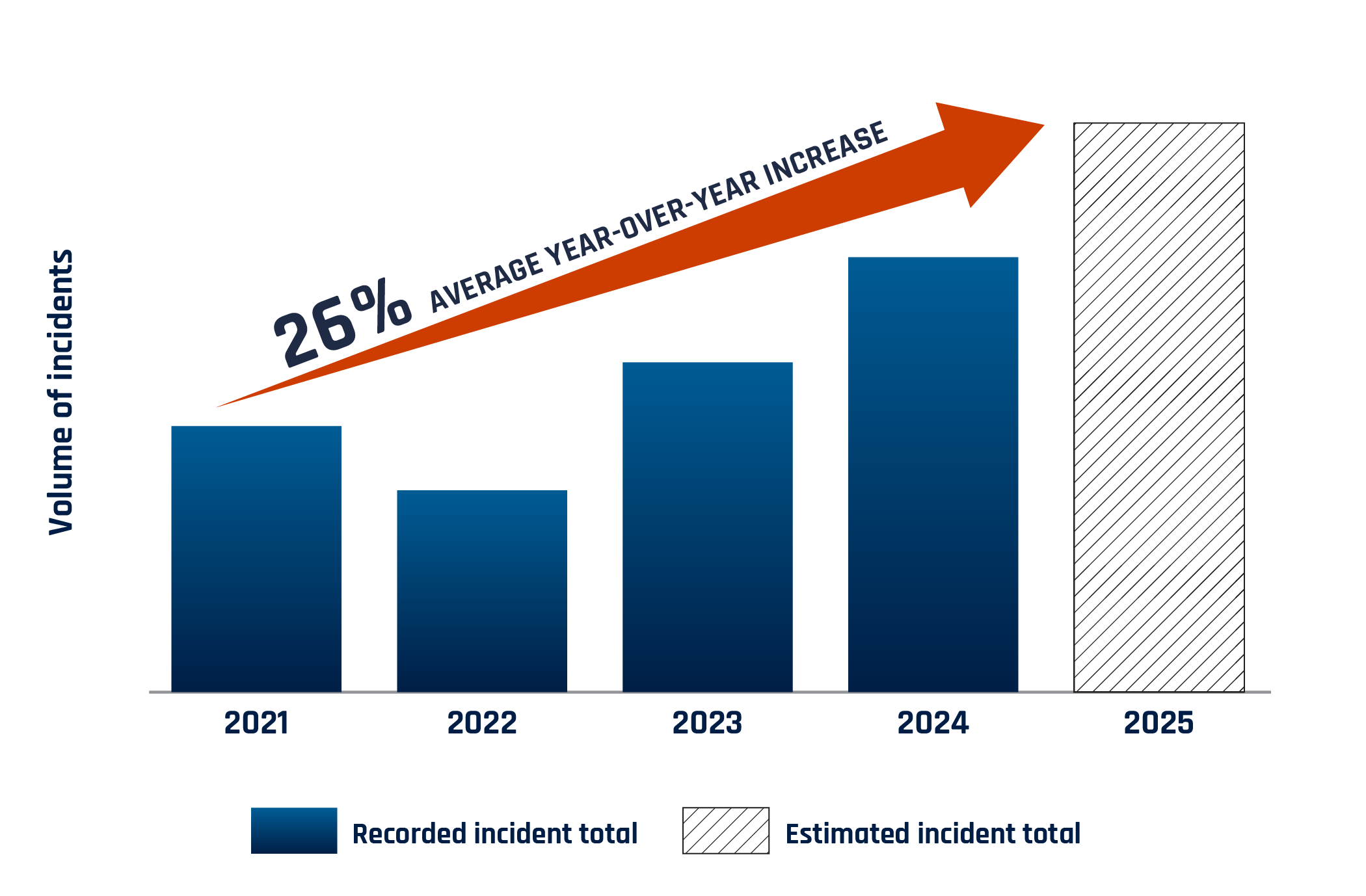

As outlined in the Cyber Center’s National Cyber Threat Assessment 2025-2026, law enforcement actions and geopolitical events can cause fluctuations in cybercrime activity. However, we assess that ransomware incidents in Canada are on the rise overall and continue to increase annually across most sectors.

Ransomware payments have fluctuated over the past 4 years, which could be a result of fewer or smaller payments made by victims combined with an increase in the total number of Canadian victims. Although most financially motivated ransomware actors operate opportunistically, Canadian critical infrastructure will likely continue to be a desirable target due to the perception that these organizations are more inclined to pay ransom demands to minimize disruptions.

The Cyber Centre observed an increase in the number of ransomware incidents in 2024 compared with 2023. We assess that it is very likely that RaaS has lowered technical barriers to entry for threat actors into the ransomware ecosystem and allowed for the proliferation of sophisticated tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) that are leveraged against Canadians and Canadian organizations. We assess that, due to underreporting, the number of ransomware incidents and payments is almost certainly higher than what is shown in the figures below.

Long description - Figure 1: Growth from 2021 of Canadian ransomware incidents known to the Cyber Centre

A chart indicates that, despite a small reduction in total recorded ransomware incidents in 2022, there has been a 26% average year-over-year increase from 2021 to 2024, and that average is estimated to continue through 2025.

In 2024, the top 3 ransomware threats to Canada were:

- Akira: Akira is a RaaS group that emerged in April 2023 and is very likely connected to the disbanded ransomware group Conti.Footnote 26 The group operates 2 ransomware variants. It exfiltrates victim data before encrypting victim devices and leverages stolen data to perform double extortion.Footnote 27 Akira has been used to impact industries in manufacturing and telecommunications globally and in Canada.Footnote 28

- Play: Play is a ransomware group that emerged in June 2022 as a closed group and shifted to a RaaS model in November 2023. The group operates a ransomware variant by the same name and leverages a double extortion model.Footnote 29 Play has been used to impact organizations in the information and technology and professional services sectors globally and in Canada.Footnote 30

- Medusa: Medusa is a RaaS group that emerged in June 2021. The group operates a ransomware variant by the same name and leverages a double extortion model. Medusa has been used to impact various critical infrastructure organizations, as well as information and communications technology sectors globally and in Canada.Footnote 31

Ransomware can have severe impacts on an organization’s business operations and the security of their sensitive information. It can also damage an organization’s reputation. All of this can impact an organization’s competitiveness across its sector and within the broader Canadian economy.Footnote 32

Canadian Survey of Cyber Security and Cybercrime

Statistics Canada conducts the Canadian Survey of Cyber Security and Cybercrime (CSCSC) on behalf of Public Safety Canada. This survey gathers information on the financial and operational effects of cybercrime on Canadian businesses. It also gathers information on the readiness of Canadian businesses toward implementing proactive cyber security and managing security incidents. The most recent CSCSC data, published in October 2024, uses information gathered in 2023 from a sample of over 12,000 Canadian organizations. The survey provides key insights into the prevalence and impacts of cyber incidents, including ransomware, in addition to evolutions in security postures and procedures among Canadian businesses.Footnote 33

13% of businesses reporting cyber security incidents identified ransomware as the method of attack, a 2% increase since the 2021 CSCSC.

Following an increase of CAD 200 million from 2019 to 2021, the total recovery costs associated with cyber security incidents in 2023 doubled to CAD 1.2 billion.

Approximately 22% of businesses reported that formal training was provided to non-IT workers to improve and progress their cyber security skills.

There was an 11% decrease in organizations employing cyber security workers, primarily due to the use of third-party cyber security consultants and MSPs.

Cyber snapshots

Across Canada, organizations are increasingly forced to reckon with the evolving cyber threat landscape. Ransomware can have serious consequences for business functions, supply chain management, and customer confidence when cybercriminals disrupt operations, steal or leak sensitive information.

We assess that ransomware actors will continue to target Canada and Canadian organizations in the next 2 years. Examining publicly reported case studies of ransomware incidents can help contextualize the impacts to business functions and communities that rely on these organizations’ services. Understanding the real-life implications of ransomware can help Canadians recognize the severity of the issue and recognize how they, their businesses, and their communities may be impacted.

Public sector

Example one

A Canadian entity in the public sector reported that they were the victim of a cyber security breach. The breach caused widespread technical outages, leaving services unavailable for months. Rather than pay the ransom, the entity chose to rebuild their systems.

Following the initial detection of suspicious activity, the entity engaged with its incident response team, external security consultants, law enforcement, and legal counsel to investigate and contain the breach.

An impact assessment revealed that threat actors initially accessed the network but remained dormant for months before exfiltrating data. The stolen data included information on staff and their dependants. The data also included information on customers, contractors, stakeholders, volunteers, and job applicants, including personal, medical, and financial information.

Example two

A Canadian public sector organization was the target of a ransomware attack that significantly disrupted operations.

Within days, the organization contained the incident and recovered most of their services from system backups. It maintained that no ransom was paid and that, following a forensic analysis, it found no evidence that the threat actors retrieved any sensitive or personal information.

Despite the restoration of some services, certain systems remained unusable for months after the incident. Recovery and rebuilding costs were estimated in the millions of dollars.

Private sector

Two Canadian logistics companies experienced a breach involving customers’ personal information.

The entities reported the attack to the potentially affected parties, relevant federal authorities, and the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada (OPC). The OPC launched an immediate investigation to evaluate the effectiveness of the precautions in place to safeguard the sensitive information.

A ransomware group claimed responsibility for the attack and alleged to have stolen a significant volume of documents.

Retail sector

A large Canadian health retailer reported a ransomware attack that forced operations to be shut down for days while systems were rebuilt.

The organization refused to pay the ransom and deployed countermeasures to protect their networks from additional compromise. External experts and law enforcement were engaged to contain the threat and restore systems. The entity stated that the ransomware attack compromised data related to their human resources and finance departments, including some employee data.

Education sector

An education technology organization announced that a threat actor had leveraged a compromised credential for a customer support portal to gain access to sensitive data. The impacted databases contained information from millions of individuals.

The organization reported the incident to relevant law enforcement authorities, and made the decision to pay the ransom. Despite assurances from the threat actor that the stolen information would be deleted, it was announced that the threat actor continued to contact victims in an attempt to re-extort them with the same data from the initial incident.

Energy sector

A Canadian entity in the energy sector confirmed that it was the victim of a ransomware attack that resulted in the leak of sensitive personal and banking information from many current and former customers. The entity notified all impacted customers and offered credit monitoring and identity protection at no cost.

The entity confirmed that they did not pay the ransom demand and enacted their incident response protocols, engaging with cyber security experts to assess the impact of the attack and rebuild and restore impacted systems.

Myths and misconceptions

A key step to Canadians bolstering their baseline resilience to cyber attacks is debunking common misconceptions and beliefs. This includes Canadians building a better understanding of their proximity to threats and the sensitivity of their personal or business information, as well as taking important steps for incident response.

“We’re too small to be a target”

We assess that any Canadian organization, small or large, can likely be susceptible to cyber threats and the impacts of ransomware. Although some ransomware groups maintain a self-proclaimed “moral code,” whereby they refrain from targeting certain organizations (for example, hospitals, charities, government agencies, religious institutions), others will target any organization.Footnote 34

Groups that are more technically sophisticated and well resourced may conduct proactive research on companies to identify those most likely to pay ransom demands. Meanwhile, other threat actors prioritize increasing dedicated leak site posts, regardless of victim size, to bolster their reputation.

Smaller businesses often use MSPs to manage parts of their operations, or integrate parts of their supply chains with multiple other entities. This can increase the threat surface for these businesses if those third parties experience compromises.

Resources:

“We don’t need all these cyber security tools and rules”

Every time Canadians leave their homes, it is very likely that they mitigate any potential risks by closing their windows, locking their doors, and turning on their security systems.

Similarly, implementing basic cyber hygiene practices can significantly reduce the likelihood of ransomware attacks. Routine training and education for employees help foster personal diligence and strengthened cyber security awareness. This can have a tremendous impact in preventing common forms of entry for ransomware, including:

- spoofed websites

- phishing messages

- compromised login credentials

Flagging suspicious content and taking a moment to think critically and validating URLs and email addresses as well as are simple steps that individuals can take to prevent malware infections.Footnote 35 Other measures that individuals and organizations can take to protect themselves against ransomware include:

- routine backups

- automatic updates

- security tools

Resources:

- Protect your organization from malware

- Tips for backing up your information

- Developing your incident response plan

- Steps for effectively deploying multi-factor authentication (MFA)

- Best practices for passphrases and passwords

- Password managers: Security tips

- Cyber hygiene best practices for your organization

“Paying the ransom is the easiest way to get our data back”

There is no guarantee that threat actors will unlock systems or return stolen data if organizations that experience a ransomware attack pay the demanded ransom. Threat actors can copy the data and use it to revictimize an organization or its customers for more money.Footnote 36

Cyber insurance as a proactive protection measure against ransomware can encourage organizations to align their cyber security postures with insurance policy standards. However, if insurance policy documents are not properly protected on an organization’s website or systems, sophisticated ransomware actors could obtain information on coverage amounts and leverage it in ransom negotiations to maximize their payment.Footnote 37

“I don’t run a business, so why should I care about ransomware?”

In the current digital landscape, countless organizations likely collect and store your sensitive information. If those corporations suffer a ransomware attack, your personal data could be indirectly compromised. A ransomware attack can lead to spillover effects that can impact Canadians, regardless of their job or their diligence with data. When cyber attacks disrupt organizations that provide essential services, they can severely limit public access to pharmaceuticals, transportation, internet services, and other critical resources.

“I don’t care if my data is out there—they can have it”

Organizations are increasingly responsible for handling immense amounts of personal data from Canadian customers, from sensitive financial details to contact information and health records. In the aftermath of a ransomware attack, threat actors often sell compromised consumer data on the dark web. Once your data has been compromised, it will very likely remain in this ecosystem. This increases your vulnerability to threats like targeted phishing email campaigns, which can then impact your clients, family, and friends.Footnote 38

Business owners should be concerned about their data security since a compromise of their information (such as intellectual property) can directly impact their reputation, financial security, and market competitiveness.

Reporting ransomware

If you or your organization experience a ransomware attack, we advise you to report it to your local authorities, the Canadian Anti-Fraud Centre, and the Cyber Centre (through My Cyber Portal or by email at contact@cyber.gc.ca).

Reporting cyber attacks allows relevant authorities to properly investigate attacks and identify the source of the compromise to protect your organization and others from future incidents.

Understanding the ransomware landscape in Canada depends on our comprehension of the size and nature of threat actors. By reporting cyber attacks, you help contribute to a safer, smarter Canada.

Outlook

We assess that ransomware will remain a significant threat to Canada, requiring substantial attention from Canadians in the coming years. As organizations become more integrated into the digital landscape, increasing exploitation opportunities for threat actors, their infrastructure and sensitive data will very likely continue to be at risk of compromise by ransomware.

Cyber threat actors have, and will continue to, evolve their TTPs, including extortion tactics and victim demography, to increase the impact of their attacks and their opportunities to reap financial reward. However, Canadian organizations can do a lot to protect themselves from these threats. It is crucial that Canadian organizations looking to safeguard their systems and information consider cyber security at the core of everything they do. This includes implementing fundamental cyber security practices such as patching operational technology, enabling automatic updates and MFA, and encouraging secure-by-design. Canadian organizations should also take advantage of the tools available to them — such as the malware detection and analysis tool, Assemblyline, developed by the Cyber Centre — to continuously monitor their networks and stay vigilant of evolving threats.

Continued collaboration between domestic law enforcement, the private sector, and international allies will be required to bolster understanding of the threat ecosystem and to coordinate appropriate proactive and responsive actions to prevent the global impact and spread of ransomware.

The Cyber Centre works around the clock to detect and defend against ransomware and other similar cyber threats. One of the ways we do this is by providing pre-ransomware notifications to warn potential victims during the initial stage of a ransomware incident. Through these notifications, cyber defenders can pinpoint and stop ransomware attacks before any data is compromised. In the 2024 to 2025 fiscal year, we issued 336 pre-ransomware notifications to over 300 Canadian organizations, resulting in an economic savings of up to CAD 18 million.

For more information on how Canadians and Canadian organizations can protect themselves against the ransomware threat and bolster their overall cyber resilience, we encourage them to consult our Cyber Security Readiness Goals, Ransomware Playbook, and other cyber security guidance available on the Cyber Centre website.

Glossary

- Artificial intelligence (AI)

- A subfield of computer science that develops intelligent computer programs to behave in a way that would be considered intelligent if observed in a human (for example, solve problems, learn from experience, understand language, interpret visual scenes).

- Big game hunting

- The practice of targeting critical infrastructure and other sensitive organizations because they are perceived to be more likely to pay larger ransoms to avoid critical service disruptions or to protect sensitive information.

- Botnet

- A network of computers forced to work together on the command of an unauthorized remote user. This network of compromised computers is used to attack other systems.

- Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS)

- A regional organization established in 1991 that comprises 9 member states previously part of the Soviet Union: Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Moldova, Russia, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan.

- Cryptocurrency

- Virtual assets that use cryptography to protect and affirm their ownership. Units of cryptocurrency are called “coins,” such as Bitcoin and Ether. Cryptocurrency transactions are generally recorded on their respective blockchains. “Tokens” represent a certain value of “coins” and can be used to buy certain goods and services. Cryptocurrencies operate on a peer-to-peer system and are not managed by a central authority like a bank, government, or country.

- Cyber insurance

- A specialized product intended to help businesses manage losses caused by computer networking threats such as data breaches and cyber extortion. Cyber insurance can cover a range of cyber events, including confidential data breaches, cyber extortion, and technology disruptions.

- Dark web

- An unindexed segment of the Internet that is only accessible through specialized software or network proxies. Due to the inherently anonymous and private nature of the dark web, it facilitates a complex ecosystem of cybercrime and illicit goods and services trade.

- Decryptor

- A specialized tool designed to help businesses recover encrypted files without having to pay attackers for decryption keys.Footnote 39

- Dedicated leak sites

- Websites where ransomware threat actors publish data stolen from companies that refuse to pay the ransom. These sites can contain sensitive information such as login credentials, intellectual property, and personal and financial data. They put victim organizations at risk of security breaches, identity theft, financial fraud, reputational damage, and legal consequences.Footnote 40

- Deepfakes

- Content that has been digitally manipulated and is intended to deceive. This includes artificially generated images, audio, and videos.

- Distributed denial of service (DDoS)

- A type of cyber attack in which threat actors aim to disrupt or prevent legitimate users from accessing a networked system, service, website, or application.

- Double extortion

- When ransomware actors exfiltrate files before encrypting them and threaten to leak sensitive information publicly if the ransom is not paid.

- Encryption

- Converting information from one form to another to hide its content and prevent unauthorized access.

- Exfiltration

- The unauthorized transfer of data from a network, system, or device.Footnote 41

- Generative AI

- A class of AI models that emulate the structure and characteristics of input data to generate synthetic content. This can include images, audio, text, and other digital content.Footnote 42

- Initial access brokers

- Threat actors that sell access to corporate networks.Footnote 43

- Large language models

- Artificial neural networks that are trained on very large sets of language data using self- and semi-supervised learning. Large language models initially generated text via next-word prediction but can now take prompts so that users can complete sentences or generate entire documents on a given topic. Training on exceptionally large datasets allows the model to learn sophisticated linguistic structures and the biases or inaccuracies found in that data.

- Malware

- Malicious software designed to infiltrate or damage a computer system, without the owner’s consent. Common forms of malware include computer viruses, worms, Trojans, spyware, and adware.

- Managed service providers (MSP)

- Companies that offer a range of information management and information technology services. This includes physical, virtual, or cloud infrastructure, as well as providers who manage stored data primarily in a virtual environment.

- Multi-factor authentication (MFA)

- A tactic that can add an additional layer of security to your devices and accounts. Multi-factor authentication requires additional verification (like a PIN or fingerprint) to access your devices or accounts. Two-factor authentication is a type of multi-factor authentication.

- Phishing

- An attempt by a third party to solicit confidential information from an individual, group, or organization by mimicking or spoofing a specific, usually well-known brand, typically for financial gain. Phishers attempt to trick users into disclosing sensitive personal data, such as credit card numbers or online banking credentials, which they may then use to commit fraudulent acts.

- Ransomware

- Type of malware that denies a user access to a system or data until a sum of money is paid.

- Ransomware-as-a-Service (RaaS)

- A core group of developers sell or lease their ransomware variant to other threat actors, called affiliates. The core developers will allow affiliates to deploy their ransomware in exchange for upfront payment, subscription fees, a cut or profits, or all 3.

- Social engineering

- The practice of obtaining confidential information by manipulating legitimate users. A social engineer will often trick people into revealing sensitive information over the phone or online. Phishing is a type of social engineering.

- Symmetric cryptography

- A cryptographic key is used to perform a cryptographic operation and its inverse operation (for example, encrypt and decrypt, create a message authentication code and verify the code).

- Tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTP)

- The behaviour of an actor. A tactic is the highest-level description of this behaviour, while techniques give a more detailed description of behaviour in the context of a tactic, and procedures an even lower-level, highly detailed description in the context of a technique.Footnote 44

- Vulnerability

- A flaw or weakness in the design or implementation of an information system or its environment that could be exploited to adversely affect an organization’s assets or operations.